Some Oregon Country Fair mischief is part of innocent tradition, some practices are heavily frowned upon and others warrant police intervention.

Unwelcomed activity at the Fair is deterred conventionally, with law enforcement, and creatively, with a volunteer security team numbering in the hundreds. Sneaking in, drug use and dealing, inappropriate behavior and theft are among the troublemaking OCF must curb every year.

“Last year, we did have a series of thefts that happened in some of our campgrounds and we apprehended the individual,” OCF General Manager Charlie Ruff says, noting that some of the stolen items were returned to their owners.

OCF pays the Lane County Sheriff’s Office (LCSO) to staff entry and exit points at the Fair, and the Sheriff’s Office mans the area with additional deputies, says Carrie Carver, LCSO’s public information officer. Fairgoers are less likely to drink and drive or partake in other illegal activities, Carver says, if they know law enforcement is around.

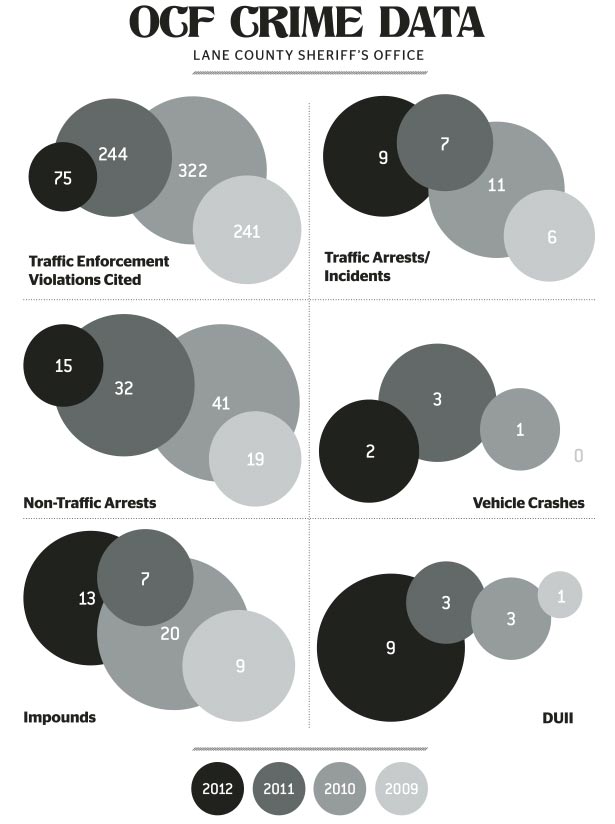

Most Fair-related citations given out each year are for traffic violations — parking, driving uninsured, driving while suspended, speeding and, most commonly, seatbelt tickets, Carver says. “Non-traffic arrests” make up the second most common group of violations, which includes unlawful possession of a controlled substance, menacing, trespass, assault and warrant arrests. Sheriff’s office staff also doles out DUIIs.

“Years ago, sneaking into the Fair was a local pastime in the Eugene area,” Ruff says. “As time went on and the event matured, we became much better at credentialing our folks.”

Long-time security volunteer Chad Butler says the passes were easier to hand off to friends when they were buttons. “One of the bigger issues that we deal with isn’t necessarily people sneaking in without credentials; it’s people coming in with fake credentials.”

According to Butler, the passes are difficult to copy and attributes the recent rise in counterfeit passes to technology being more accessible. “We try to get good at looking for all the different aspects of the security markings we put on these new passes,” he says.

Butler has missed one Fair since his first in 1987 and has volunteered as security since 1995. He also runs a small didgeridoo-oriented festival called In-Didj-In-Us.

“Anytime people get together in a festival or socially festive environment, you’re going to see drug use and you’re going to see people trying to sell drugs,” Butler says. “When we do catch on to that, we deal with it immediately and severely.”

Ruff says the Fair has become much more family-friendly since they banned alcohol and drugs in the mid ’90s.

Upstairs in the information booth, Butler says, people look for entrants who have previously been kicked out. On the opening Friday of Fair, “their eyes are scanning that crowd rush,” he says, “and within 15 minutes of when the Fair opens, we’ve picked up one or two people who’ve been kicked out from previous years.”

He notes that women often feel comfortable topless at OCF. “There’s always going to be those creeps who really can’t stop wanting to stare at shirtless women or wanting to say inappropriate things,” Butler says. Security has a positive talk with the person, Butler says, to help them understand respect issues, rather than calling them a creep or being aggressive. “Asking for what you need is the best way to get what you want, and we’ve always got that at our fingertips,” he says.

Ruff says security crews go through “humanistic intervention training” to teach them to de-escalate and handle things lovingly.

Butler notes that the unconventional approach to security has influenced some other fairs and festivals to drop the yellow-shirted authoritarian take on managing attendee behavior. “That’s something beautiful about Country Fair,” he says, “is that we turn problems into opportunities for solutions.” He says effective security at the Fair is “an ever-changing trick, and we’re into that puzzle.”