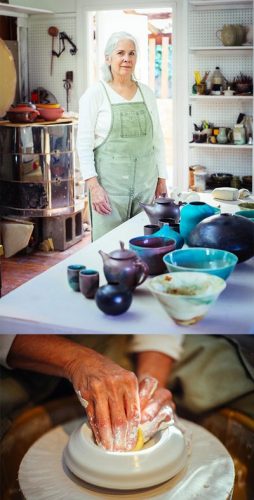

Julie Reisner, a ceramic artist from Eugene, says her first “big shock” moment came in the early ’80s when a special clay she liked was no longer available because the mineral was depleted.

“I thought, ‘Uh oh, these things are finite,’” she says. “This is like cutting down old growth.”

Pottery is an art form steeped in tradition, dating back tens of thousands of years, but it’s also an environmentally taxing tradition, one requiring artists to use gas or wood-burning kilns heating up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, firing limited resources extracted from the earth.

As issues of climate change and sustainability have confronted the pottery industry, potters have adapted to think differently about how they approach their art form, adjusting to the loss of resources and shifting towards more conservation-minded practices.

One struggle for potters, Reisner says, is how to fire their work. Lower temperatures burn less fossil fuel but also produce lower-quality pieces. Traditionally, potters have used low-fire techniques to make expendable pieces while high-fire techniques produce more refined, durable products. Some potters now use middle fire, a compromise between the two that expends slightly less fuel.

Reisner says her personal philosophy is one of durability. “I decided if I’m going to burn up all this fuel, I’m going to make the best pots I can, something that would really last.”

Brian Gillis, ceramics coordinator for the UO Department of Art, says that any practice using materials other than clays found in river beds, where water continually deposits more sediment, is technically unsustainable, and when you “lop of the top of a mountain and don’t look back,” it explains why five to 10 minerals have gone off the market in the last 20 years.

The UO, Gillis says, used to have a wood-firing kiln on campus, but the Lane Regional Air Protection Agency shut it down because of its high output of air pollutants. Now the ceramics department is shifting toward better burning efficiency and plans to bring prominent wood-firers on campus to teach improved wood-firing techniques.

The university also reclaims all its waste materials, Gillis says, and the used material gets made into small bricks for use in gardens, which the UO is planning to sell next year.

Ultimately, Gillis says, “The practice of pottery in its most basic form is about stripping the earth and changing its essence.” While pottery may shift to lower impact practices, clay-based works of art are special because of their earthen origin, and there may be no way around that basic fact.

“There’s a strong dialogue between the maker and the clay,” Reisner says. “This is a craft that is rooted in the earth.”

Check out Reisner’s work at juliereisner.com.