|

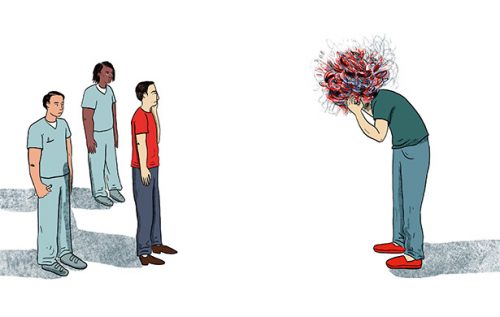

| Illustration by Lily Padula |

I spent the early ’90s in Seattle working at a gas station just off I-5, near the University District. My co-worker on the morning shift, Pete, was a tall, smart, shy guy with a cynical disposition and a tart sense of humor. He had a troubled home life — wife, a kid, nights of hollering, a visit from the cops once. Pete drank too much sometimes. But he was a gentle soul. I liked him. Lots of people liked Pete.

I knew he was fucked up, but I told myself we were all fucked up. At work, during slow times, Pete and I talked in vague terms about the trials of life, our angst, our martyrdom, the bullshit of existence. Shop talk. That’s what men do, I figured.

One day at the gas station Pete pulled me aside. He wanted to show me something. He swung open the sliding door of his VW bus, reached under the seat and pulled out a pistol. Cool, I said. That’s a helluva gun, I said.

Word has it that the day before he was killed, Pete tried to check himself into a psych unit and was turned away. He’d sought help for his depression several times, was frustrated by the lack of help, the shortage of answers. I see now that him showing me the gun might have been a cry for help, but with Pete it was tight to the chest, all cues and clues. Outward talk, inward screaming.

On June 25, 1993, Pete committed a pretty spectacular suicide by cop during Seattle rush hour, pulling his van onto a grassy knoll and brandishing the pistol until he was gunned down by a state trooper. The detail in The Seattle Times report (wkly.ws/22l) chills me now: “a troubled, sick little boy”; “in a way, I’m not surprised”; “he sounded very disoriented”; “was asking for help, or looking for help … it was kind of a subtle thing.”

Darkness Visible

Watching someone trip through the cycles of mental illness is terrifying. It utterly baffles our powers of comprehension. Fear leads to frustration, anger, depression and a sense of helplessness that is overwhelming and isolating. Like addiction, with which it can be so inextricably related, mental illness spreads outward in chaos, affecting everyone it touches.

Did people in the Dark Ages suspect they were living in the Dark Ages? It’s tempting, considering recent circumstances — the endless mass shootings, the warehousing of the mentally ill in jails and prisons, the preponderance of the sick, homeless and addicted in Eugene — to tumble into despair over the state of mental health in this society.

Yes, we emptied out the cuckoo’s nest institutions with their sadistic Nurse Ratcheds and drooling lobotomies, but we emptied them into nothingness. The paucity of ground-level resources already stretched thin has created a pervasive crisis where people experiencing mental-health issues are funneled through the system again and again and again, with no endgame in sight.

And yet, there are glimmers of hope in the darkness. Most of the mental health advocates I’ve spoken with acknowledge the current crisis while also pointing to transformation in the way mental health care is delivered, with a focus on integrated care at the ground level as well as greater public awareness of the signs and symptoms of mental health crises — as opposed to the familiar bottle-up-and-explode model, with its often deadly consequences.

Oregon Rep. Val Hoyle points out that recent legislative efforts have sought both to expand the definition of “dangerousness” in instances of mental health crisis and to stop the cycle in which individuals are admitted and discharged over and over from mental health care facilities.

Hoyle, who is open about dealing with mental-health issues with close family members, says that recognizing the symptoms of mental illness is a crucial step to getting people the care they need, including early intervention. “That means us as a society becoming more aware,” she says. “And it’s not going to get better soon, until we start treating this like the epidemic that it is. We need a stronger safety net, and we need an integrated system.”

To this end, Hoyle cites a handful of bills, including HB 3347, a civil commitment statute that expands the definition of dangerous behavior to cover any actions putting a person “at risk of harm in the near future”; HB 2023, or the “warm hand-off” bill, calling for a comprehensive discharge plan to prevent the “revolving door” of endless emergency room visits; and HB 2948, which clarifies the conditions for disclosure under HIPAA, allowing for families and agencies to be notified when a patient is at risk of suicide.

When it comes to mental illness, Hoyle says, “we need to remove the stigma and also make people more aware of what the symptoms are. What should we be looking for? Before a terrible shooting. Before a suicide.”

Fine Line

“Our system, I know it’s pretty broken right now,” says division manager Carla Ayres at Lane County Behavioral Health. “I don’t know that anybody’s at fault. The problem right now is becoming so great that everybody’s seeing it at multiple levels, and hopefully that will institute some kind of change.”

Changes over the past couple of years, including transformations in health care brought on by the Affordable Care Act, have led the organization to rethink the way it serves the public. A more integrated, tiered system is taking shape, including team-based care that gathers together doctors, nurses, clinicians, assistants and supervisors, all with a stronger focus on peer-based support.

Ayres says the movement in Lane County is away from “criminalizing mental health” and towards providing basic necessities such as housing and access to public services. She praises organizations like National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and White Bird, as well as the latter’s street-based assistance through CAHOOTS.

And yet there is only so much an organization can do. “Folks think we have more power than we do,” Ayres says. For instance, public officials can’t just pick up a person who is acting erratically and forcibly medicate her against her will, no matter how much the family pleads for such a thing. Talking nonsense and hearing voices are not crimes, and they may or may not be indicators of dangerous tendencies.

Ayres’ colleague, civil commitment investigator Ivan Sumner, says that the tension of voluntary versus involuntary commitment centers on the idea of dangerousness. Prior to HB 3347, unless someone was threatening homicide or suicide, they could not be held against their will. “Dangerousness is not a bad attitude,” Ayres says. “We really are on a daily basis called upon to make a differentiation between the two.”

There is also something called a 2MD or physician hold, a short-term emergency hold in a psychiatric facility like the former Johnson Unit, at the end of which a patient is assessed and may, if still deemed at risk of harming himself or another, face a civil commitment hearing. Ayres says the county processes about 700 such holds a year, with about 9 percent of these taken to hearings. “The rest are discharged,” he says.

Ayres guesses that the percentage of people undergoing repeat 2MD holds in a year is more than 30 percent.

Let Me Help You

Fast-forward about 15 years from Pete’s death, give or take: I’m on the phone with my brother. He and my father are pulled over at an I-5 rest stop somewhere between Seattle and Bellingham, and he won’t get back in the car. My brother says babies speeding by on the freeway are screaming at him — screaming at him because he is evil incarnate.

Days later he’s pacing the room of my second floor apartment in Seattle. Every minute or so he splits the blinds with shaking hands and peeks through. “Do you hear that?” he asks my father and me. “Do you hear the sirens?” We don’t. He stares at us, confused and pleading, paranoia granting him a sniper’s intensity.

After hours upon hours of wheedling and arguing and begging, we finally get my brother to a hospital downtown, where he haltingly agrees to undergo a psychological assessment. They take him through the doors and down the hall, leaving us to wait in spent silence. I’ve never seen my father look so tired, so old.

The intake woman at the hospital informs us that my brother is experiencing a psychotic break, and that immediate commitment is recommended. The relief I feel at hearing these official words is nearly ecstatic. Hell hath a name: psychotic break. Do it, we say. Fix him. Help us.

But my brother has other ideas. “You guys are just fucking with my head,” he says, his pupils vibrating in his skull. He doesn’t want to be brainwashed, he says. He doesn’t want medication. He doesn’t need help. Stunned, we watch him stomp out the hospital doors.

“Just let him go,” I tell my father. “I don’t fucking care anymore.” And as I watch my brother walk away, the rage boils up inside. Suddenly I want to run up behind the selfish little prick, grab him around his skinny little throat and choke the life out of him. I want to annihilate him. I want to make him pay for the pain and agony he’s inflicted on us all.

Susan Matthews volunteers as a family-to-family coordinator at NAMI Lane County. Matthews first came to the organization when a relative had “what people call a mental breakdown … I knew nothing about what to expect or what was happening,” she recalls.

Matthews says she received a much-needed education about mental health at NAMI, where she was given “information about how to communicate with him and be supportive as possible. It was wonderful to come to a group of people who are all dealing with the same stuff.”

NAMI Lane County Executive Director José Soto-Gates says that such support goes a long way in diminishing the stigma surrounding mental illness as well as the isolation and fear it inspires, not just for those in crisis but for the individuals and families trying to help them.

“Everything we do is peer-delivered services, teaching from lived experience,” Soto-Gates says. “A lot of people have been turned off by some of the traditional systems. We try to act as kind of a front door for people who are seeking help.”

As opposed to the old model of the “zombie warehouse,” where institutionalized patients are zonked on mind-numbing medications by authoritarian doctors, Soto-Gates says the goal at NAMI is to advocate for a deeper understanding of mental illness. The idea is to provide broad public access to resources, including peer-support groups, safe housing and patient-based education about things like the side effects of particular medications.

“One of the main increasers of mental illness is isolation,” says Soto-Gates, who notes that one in four people in Lane County are currently dealing with a mental health challenge. Instead of judging and stigmatizing people with mental health issues, he says, the goal at NAMI is to listen to them — to validate an emotional state by saying, “we hear you.”

The idea, Soto-Gates says, is to let a person in crisis know that “he is not on this journey by himself,” because “a lot of the homeless folks out there, they’ve lost that support, so they just continue to get worse and worse.”

Safety Nets

“You don’t know it, but you are out of control,” says my friend Celine over a cup of coffee in downtown Eugene. She’s trying to describe how it feels when she goes off the medication she takes for schizoaffective disorder. “You’re just so far from reality you don’t want to hear anything. It’s hard for me to think about what I was thinking.”

When she’s on medication, as she is now, Celine is a sweet, compassionate, whip-smart woman who laughs generously. She rarely misses a beat, no matter what the conversation. Off her meds, Celine is prone to wandering the winter streets of Eugene barefoot, in terrycloth shorts and a T-shirt, speaking in devout terms about alien pregnancies and galactic conspiracies, with expansive points of reference that catapult through history, from the Big Bang to Celine Dion.

Talking with Celine, I remind her that, the last time she was too far out, I suggested she get back on her meds and she hissed, “Don’t talk about that.” I ask her what I could have done differently, and she shrugs. So what worked this time around?

“I was around somebody who had a diagnosis,” she says. “It helped me realize I needed help … I had somebody on the streets help me every day. He cleaned up my mess, kept me safe, which was very helpful. He advocated for me between different people.”

Instead of someone coming at her — a cop, a doctor, me — and telling her she’s sick and requiring medication, Celine’s resistance was dismantled by the ministrations of another person whose mental health history is similar to her own. This is called peer-delivered support: the notion that the strongest trust is fostered between individuals with a shared experience. This is a centerpiece of 12-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous, where drunks are tasked with helping other drunks.

“There’s more resources now than there was before,” Celine says, noting that folks in crisis have access to a constellation of community resources such as Lane Independent Living Alliance, White Bird, ShelterCare and Laurel Hill, where she currently has an apartment.

Such organizations, with their coordinated health and living services, are indispensible in “helping people out of the hospital and integrating them back into society,” Celine says. “I have a lot of hope, especially in Eugene.”

Please read the other half of this feature, “Into the Institution,” by Camilla Mortensen.