It seems like only yesterday, and not 20 years ago. And I don’t know why or how, but Lewis Puller’s suicide “got” to me. But, what I wrote 20-plus years ago still stands: Another Vietnam vet has committed suicide. I do not know the particular demons which finally drove Lewis Puller to kill himself. I do know I have a few of my own that propelled me to the edge in 1975.

Vietnam must be the craziest war in history: more veterans — at least twice as many — have committed suicide after the war as died in the war. And that does not include single-car accidents or drug or alcohol overdoses. It is as if we Vietnam vets are being damned for our sins.

What are our “sins” that push us to act on what the Catholics call a mortal sin?

Lewis Puller Jr., son of the legendary Marine General Lewis “Chesty” Puller, was in a lot of pain because of his loss of both legs, his terrible addiction to drugs, perhaps mistakenly prescribed, and, worst of all, a failing marriage to a wife whose past support had been vital. In my own case, I felt guilt over having inadvertently walked our patrol into an ambush of “friendly fire.” But I believe those may be superficial demons. Something more fundamental is going on.

I think that one of the biggest demons is what I will call justifiable guilt. Everyone likes to say, “That’s war. It’s not your fault.” Yet other veterans of other wars have handled worse and not blown themselves away.

In her seminal book, Long Time Passing, Myra MacPherson noted the parallels between Vietnam veterans and German veterans of World War II, particularly the high rates of suicides in both groups. I believe she was on to something that we as veterans and Americans have missed or, worse, denied and repressed: the sin of participating in a bad war, and the very real need to atone for that sin as a psychologically healing act.

I am not speaking in terms of religious or spiritual mumbo-jumbo. No matter how noble our intentions, Vietnam was a very bad thing. There was an almost cosmic level of damage inflicted between two societies. Damage to them, damage to us; the statistics are so often recalled. But look at them again through the prism of humanity and dwell on the pain behind the sterile numbers.

Fifty-six thousand Americans were killed. More than 2,500 are missing. At least 1.4 million Vietnamese were killed. Two million were wounded in a country with no medical facilities to care for them. Ten million were driven from their homes. Thirty million gallons of Agent Orange poisoned the soil of Vietnam and 14 million tons of explosives, not counting napalm and phosphorous, ripped the land apart.

In the south of Vietnam, the land of our supposed allies, 9,000 of 15,000 hamlets were uprooted or destroyed; more than 20 million acres of cultivable land were bombed, and the soil ruined by the resulting compaction of bomb impact craters. Over 10 million acres of forests were defoliated. The result was perhaps the most environmentally destructive war ever waged. America did all that. We did all that. And when we veterans juxtapose that waste with our suffering and that of our buddies, we face the chasm of madness and yes, evil.

How do we bridge that chasm? What good is to be found in a world so full of evil, especially if we see it in ourselves? I can’t speak for Puller or anyone else but myself, and I hope it can help. I am not overly religious, but after my own near-suicide, I forced myself to believe that it is a mortal sin, if you will, and that self-imposed hang-up has clicked in as a useful devise when I am hit with despair. It helps me to get past the immediate crisis.

I am not saying suicide is a mortal sin, or that I found the Lord, but I can assure fellow sufferers that help and comfort can be derived by behaving “as if it were so.” And when the crisis passes, I usually find that life is worth going on after all. Then I can address the meaning of what happened and, more important, transcend it.

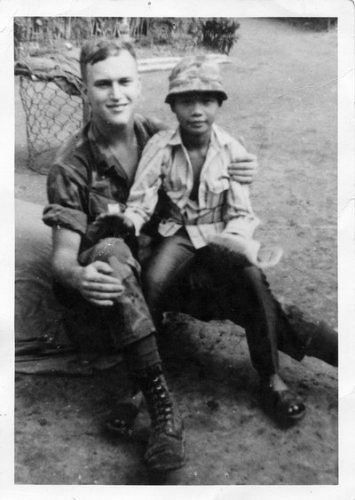

I was very lucky. I not only found a “trick” in coping with my despair, I’ve had a loving wife and family. As important, I was able to meet with and found a lot of forgiveness from those whom I victimized, the Vietnamese.

After all the spiritual talk, it also comes down to a sense of maturity in facing up to ones errors or “sins,” and to realize — truly understand — that we can forgive and be forgiven; the victim and the victimizer can find atonement.

Lewis, may you find peace. — Michael Peterson