Long associated with attempts to alleviate urban blight, urban renewal in Eugene has turned its sights upon technology, and the city is implementing a high-speed fiber network downtown.

Urban renewal has been seen as a tool for good and as a tool for destruction. Here in Eugene urban renewal money helped construct the Lane Community College (LCC) Downtown Campus that has been seen as a lynchpin in downtown revitalization.

However, urban renewal, also known as tax increment financing, funds also tore down Eugene’s historic Carnegie Library and other irreplaceable historic buildings. And former city councilor Bonny McCornack has coined the acronym DTURD (DownTown Urban Renewal District) for the funding, which she says diverts property tax revenue for schools and essential city and county services into its coffers.

In June, the Eugene City Council voted to make four projects eligible for urban renewal: improvements to the farmers market space, redeveloping the old LCC building (left vacant when the new one was built with urban renewal funds), improvements to the Park Blocks and open space and, finally, high-speed fiber.

Fiber-optic technology converts electrical signals carrying data to light and sends the light through glass fibers about the diameter of a human hair, and that technology at the same time can be flexible and hard to reach. The need to connect businesses and houses to nearby fiber optic or other internet service connections is often called “the last mile.”

Eugene is behind the times on high-speed fiber, and is not the first city to turn to urban renewal funds. Bozeman and Missoula in Montana, along with Sandpoint, Idaho, and Sherwood, Oregon, have all looked to urban renewal funds to bring broadband to town. Chattanooga, Tennessee and its “innovation district” is often cited for its internet speeds, which is as fast as 10 gigabits per second.

Efforts to bring fiber optic technology to the cities of Lane County began back in the mid-’90s when telecommunications companies began to lay fiber down along rights-of-way such as railroad lines.

In 1999 the Eugene Water and Electric Board laid 70 miles of “backbone” cable, interconnecting 25 EWEB metro-area substations and three BPA bulk power stations. It was designed to have future connections with schools like the University of Oregon, local governments and long-haul telecommunications providers. The project was later dropped when the recession hit.

Matt Sayre of the Technology Association of Oregon (TAO) is a proponent of the urban renewal funded fiber project. In 2015, TAO joined Eugene, EWEB and the Lane Council of Governments in their project to install fiber in the downtown core.

Sayre says that pilot project across four buildings has been a success. He says that when it comes to real estate the city vacancy rate is at 12 percent, but for the buildings with the high-speed fiber installed, the vacancy rate is at zero.

Sayre says as a result of the pilot project, internet speeds at the Broadway Commerce Center increased 250 percent while costs dropped by 40 percent. That’s a change from $250 for 150-megabit service, to $99 for 1,000-megabit service.

According to Sayre, Eugene is 22nd in the state in internet speeds, and the new fiber could bring in more than 200 jobs and benefit non-downtown residents by bringing down internet costs overall through the internet service providers (ISPs) that supply the connectivity. He compares the project to how a city might build the roads, but it doesn’t supply the trucks that drive on those roads.

Anne Fifield with the city of Eugene says three low-income housing projects are in the service area, and she has been in communication with the building managers. One of the goals of Eugene’s broadband plan, she says, is to “bridge the digital divide” and bring internet access to low-income households. An added bonus, she says, is users of the city’s free wifi should eventually see an increase in speeds.

EWEB and the city are working on a memorandum of understanding, Fifield says, as the city will pay for the infrastructure that EWEB will install, own and operate. Once that is done, she estimates it will take about three months to get underway and service may be available in 2017 depending on funding and ISP interest.

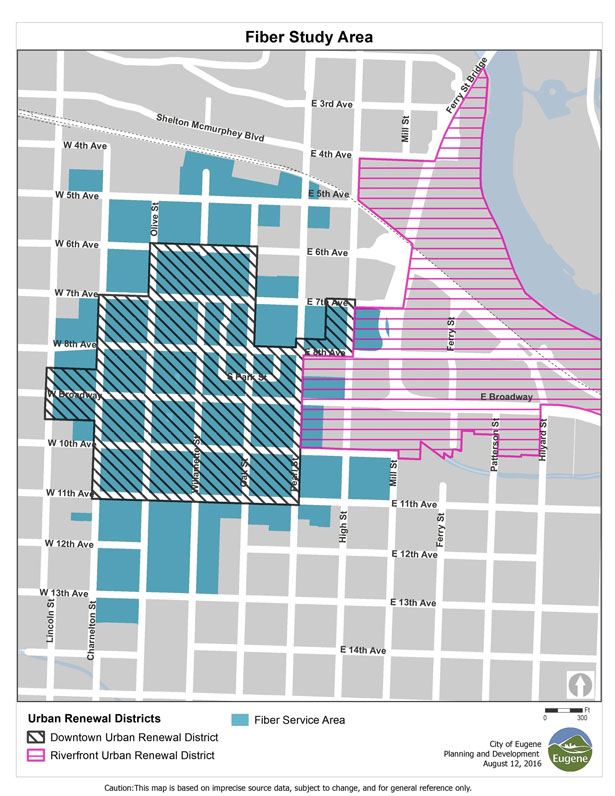

While the urban renewal funds would go to an area that roughly spans from Charnelton and High streets to 5th and parts of 13th Avenue, Sayre says there will be “stubs” that allow for expansion, calling the project “future proofed.” Fifield says the current downtown service area is determined by where there is existing underground utility infrastructure — which was originally paid for by an earlier urban renewal project that buried what had been aboveground cables.

Sayre points to companies such as Pipeworks Studio that depend on high-speed fiber. Pipeworks needs to be able to upload and download games, he says, and work is restricted by lack of available high-speed internet. Pipeworks purchased the building on Broadway in which it was leasing space earlier this year for $2.5 million, citing the prospect of high-speed broadband.

The estimated cost for the downtown fiber project is $4 million, Fifield says, with $2 million coming from the Downtown Urban Renewal District. For the rest, Fifield says the city has applied for a federal economic development grant for $2 million and that has advanced the second stage of the application process as well as received an endorsement from senators Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden and Rep. Peter DeFazio. The city is also looking at hookup fees from property owners and funding from Eugene’s Riverfront Urban Renewal District.