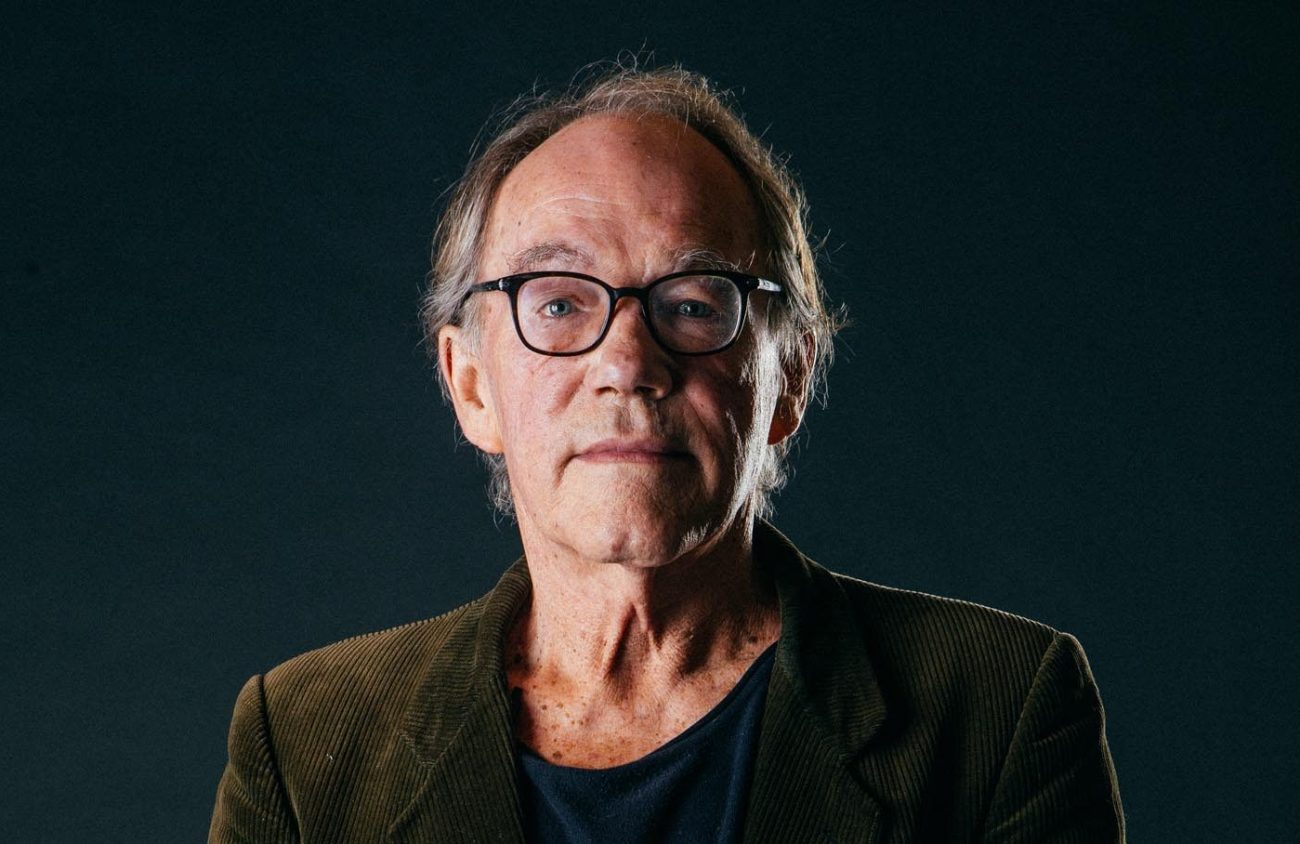

Outgoing Eugene City Councilor George Brown is not a politician; he’s a city government nerd, a bespectacled wonk. Not in the wide-eyed, soaked-in-sunny-positivity vein of Leslie Knope (of Parks and Recreation fame), but in a gruff, pragmatic, detail-oriented fashion.

After eight years on the council, the Wichita native (he’s lived in Eugene since 1970) has a basement-full of papers in his home from completed, bygone or stalled city projects. There’s a waist-high tower of documents pertaining to Civic Stadium alone, which he describes as “nostalgic” after the historic venue burned down.

Brown’s keeping it all on hand for his Ward 1 successor, Emily Semple.

On a road trip to Arizona with his wife, the couple stopped several times in California to see how other cities were addressing the same issues that Eugene struggles with, like homelessness and affordable housing. “We’re such nerds sometimes,” Brown says.

And if you’ve ever attended a City Council work session (a highly recommended jaunt, as it does, in fact, have a lot in common with Parks and Recreation), it’s obvious that not all council members do their homework like Brown, who is always carting a hefty armful of binders and rumpled papers and a list of prepared questions and topics to discuss.

But he’s a busy guy, and thus it’s time to move on from city government, at least for now, and spend more time with his family and their three cats Dottie, Pippi and Blaze. “Our boy is 13,” he says of his son. “He’s only going to be 13 once in his whole life.”

Brown and his wife also own and operate the The Kiva grocery downtown, which opened in the ’70s, where he says business is growing.

Yet, even at the end of his run in office, Brown is in no mood to wax poetic about any of it.

“I don’t really have any deep words of wisdom,” he says, followed by a big gravelly laugh. He’s even self-deprecating when talking about why he decided to run for office.

“This will probably sound very naive, but I wanted to be part of a problem-solving team,” he says, laughing again. “A lot of people maybe think that the City Council is a body of wise beings who meet amicably to solve the city’s problems. Unfortunately, it’s oftentimes not that way.”

Unlike most polished politicians, getting Brown to discuss his accomplishments in office is like pulling teeth. He jumps immediately to projects that failed, that need revising.

‘A lot of people maybe think that the City Council is a body of wise beings who meet amicably to solve the city’s problems. Unfortunately, it’s oftentimes not that way.’

After some prodding, he concedes that saving Civic Stadium from becoming a Fred Meyer (or the widely despised, tax-exempt Capstone student housing monolith — yes, Brown says Capstone originally wanted to build on that lot) is a triumph.

“I was able to help guide that through council,” he says. “There were many incidences where it was hanging by a thread.” Brown continues: “It’s owned by Eugene Civic Alliance. That was the success, because it will be public recreation space.”

Later, Brown reflects upon a longer list of city accomplishments including “having the best and most inclusive urban animal-keeping ordinance in the country,” the end of using “pollinator-killing neonicitinoids” on city property and the creation of Opportunity Village.

But Brown is much more keen to tell you about what’s still stuck in his craw. Namely, MUPTE (Multi-Unit Property Tax Exemption), City Hall and making City Council seats fulltime paid positions.

After Brown made a motion to the council to suspend MUPTE — as to prevent another Capstone fiasco — Brown and fellow Councilor Mike Clark worked on its revisions. Even so, Brown calls the new MUPTE “horribly mangled.” The main flaw, he says, is that City Council never defined standards for workforce housing, essentially allowing developers to charge market-rate prices for rent while still reaping the tax-exempt status.

He says the city did not learn its lesson with Capstone, pointing to Hub on Campus student housing on Broadway as an example of how the new MUPTE has failed: Hub is charging $200 more per bed than it showed in its pro forma, Brown says.

Next up on his shit list is City Hall. “It won’t be built in my lifetime,” he says. “Where are they going to get the money?”

While Brown doesn’t want to harp on the decision to tear down the old City Hall — spilled milk, he says — he’s still grappling with the way City Manager Jon Ruiz, the council majority and city staff are handling the process.

The city manager’s response to why he waited a year to inform the City Council of the millions of dollars in added costs for Rowell Brokaw’s City Hall design — “No particular reason” — is still ringing in Brown’s ears.

“I almost fell out of my chair,” Brown recalls. “I can’t think of any good reason why the city manager would sign contracts with the architects so out of line with standard practice.” He adds, “It’s an extra $2.5 million to the architects. That’s some serious money in this town.”

Which brings us to his thoughts on how city government runs.

The purpose of City Council is to develop policy, and then the city manager is supposed to carry out the will of the council with city staff. “Well, usually the impetus comes from the other direction; it comes from the [city] manager’s office and all the other departments and then council is expected to approve whatever has been proposed,” he says. “Usually things are just supported uncritically [by the City Council.]”

Brown suggests making City Council seats fulltime paid positions so that elected officials can devote the time needed to fully craft good policy with a public benefit, and not just rubber stamp what the city manager, an unelected administrator, and his staff recommend.

He has some advice for how the public can hold city officials accountable: Pay attention, study up, attend council and budget meetings. “Ally with other committed people and be persistent. Keep bugging us!” he says. “And when elections roll around every two years, support the candidate who truly has the public interest in mind. Above all, never give up!”

Brown doesn’t have the mindset of someone leaving public office; he’s currently reading William H. Whyte’s City: Rediscovering the Center, a study of human behavior in urban and public spaces, and he still knows what City Council work sessions are coming up.

And, of course, he says he will be there to support Semple on council in any way she needs.

“I’ll still be involved with city stuff, it just won’t be at the intensity level of being on the council,” Brown says.