It was 50 years ago today — well, more or less — that my generation found itself.

Rock ’n’ roll turned grand and pretentious that year, 1967, when Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play with a real live symphony orchestra. Here in Eugene, KLCC went on the air for the first time, and the Oregon Country Fair was two years away from being born.

Across the ocean, Vietnam was purring along like a macabre lawnmower.

That was the year of the Summer of Love.

I was 15. My friends and I sat on the beach in Los Angeles smoking dope and reading Camus and Lenny Bruce and predicting the imminent legalization of marijuana. (It was inevitable, we knew, because pretty soon all the judges and legislators would be potheads, too. It just took a bit longer than we expected.)

Cut forward half a century. I’ve been married for decades and have a grown son. I’m on Social Security and Medicare. And even as an editor at Eugene’s alt-weekly I’m definitely part of what we always used to deride as the Establishment.

And so now I’m walking into a building in Salem to see a chapter of my youth “pinned and wriggling on the wall,” as T.S. Eliot once put it, in an exhibition that’s just opened at Willamette University’s Hallie Ford Museum of Art.

Behind the Beyond: Psychedelic Posters and Fashion in San Francisco, 1966−71 was the brainchild of Oregon artist Gary Westford, a trim gray-haired fellow who greets me in the museum lobby with a rush of enthusiasm. Westford is a painter recently retired from teaching studio art and art history at Linn-Benton Community College. As a 20-something in 1968, he lived just a few blocks from Haight-Ashbury.

“I came a little late to the scene in terms of the Summer of Love,” he says. “But there was still a palpable sense in the air that all things were possible. Something big was happening.”

Much of that “something” was in the form of rock ’n’ roll concerts being staged by such bands as Jefferson Airplane, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. The streets near Westford’s apartment were alive with bright, colorful posters advertising the concerts.

He started collecting them, sometimes pulling them down off telephone poles and sometimes buying them for a dollar or two at concert halls. Then, like so many young people did in those days, he thumbtacked them to the walls of his apartment.

At least one poster in the Hallie Ford exhibition, now properly framed to museum standards, still shows Westford’s thumbtack holes. Along the way he picked up posters from a new generation of artists, including Victor Moscoso, Wes Wilson, Stanley Mouse, Alton Kelley, Rick Griffin, David Singer and Bonnie MacLean, all represented in the exhibit.

Looking back now at the imagery in those posters, which were commissioned and published by concert promoters such as Bill Graham, I see traces of the adolescent car- and surf-culture doodling that all my grade school friends and I used to do in class to infuriate our teachers: winged eyeballs, surfboards, snarling monsters, smoking tires on drag racers.

It’s good to realize, 50 years later, that a few kids who were drawing those things made a career out of it.

Westford understood, even in his youth, that these posters were more than mere decoration.

“When I was 22 and these posters were on my wall, yes, they were emblematic of our era,” he says. “But I also recognized early on that they were exciting works of art. I thought, ‘Someday I’ll do something with these posters.’”

Over the years, Westford has collected hundreds of examples from the psychedelic era of poster art, which centered on San Francisco and a small handful of music promoters and graphic artists. The exhibit he’s curated at the Hallie Ford, with the help of museum director John Olbrantz, makes a strong case that these works are in fact art and not mere ephemera. It contains just more than 100 posters, photographs and other items.

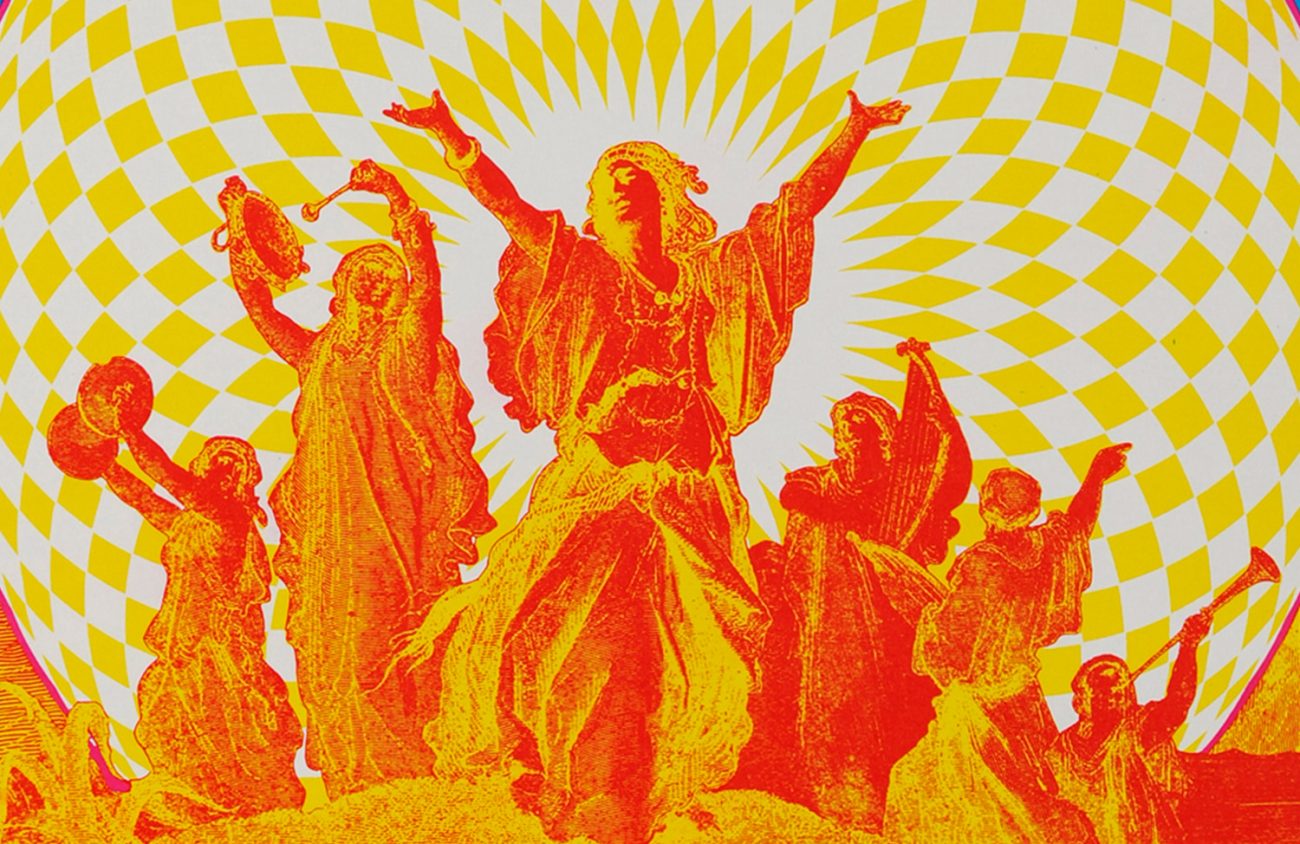

As you enter the museum, two of the first images you see illustrate the genre’s connection to a much-earlier era, the Art Nouveau period in Paris. A brightly colored poster advertising a 1967 concert in Sausalito by Big Brother and the Holding Company is practically a direct copy of a French poster by Alphonse Mucha advertising an art exposition in Paris in 1896.

“These posters are unique and they’re revolutionary,” Westford says. “The best posters from the psychedelic era will still be being shown a hundred years from now. They are visually striking and they are emblematic of an era, just as the posters of the Art Nouveau era were.”

The work quickly took off in its own stylistic directions. When Bonnie MacLean did a poster for a 1967 concert by The Who, no one cared about legible type any longer; instead, her lettering nearly disappears into the overall image and design.

Enlarge

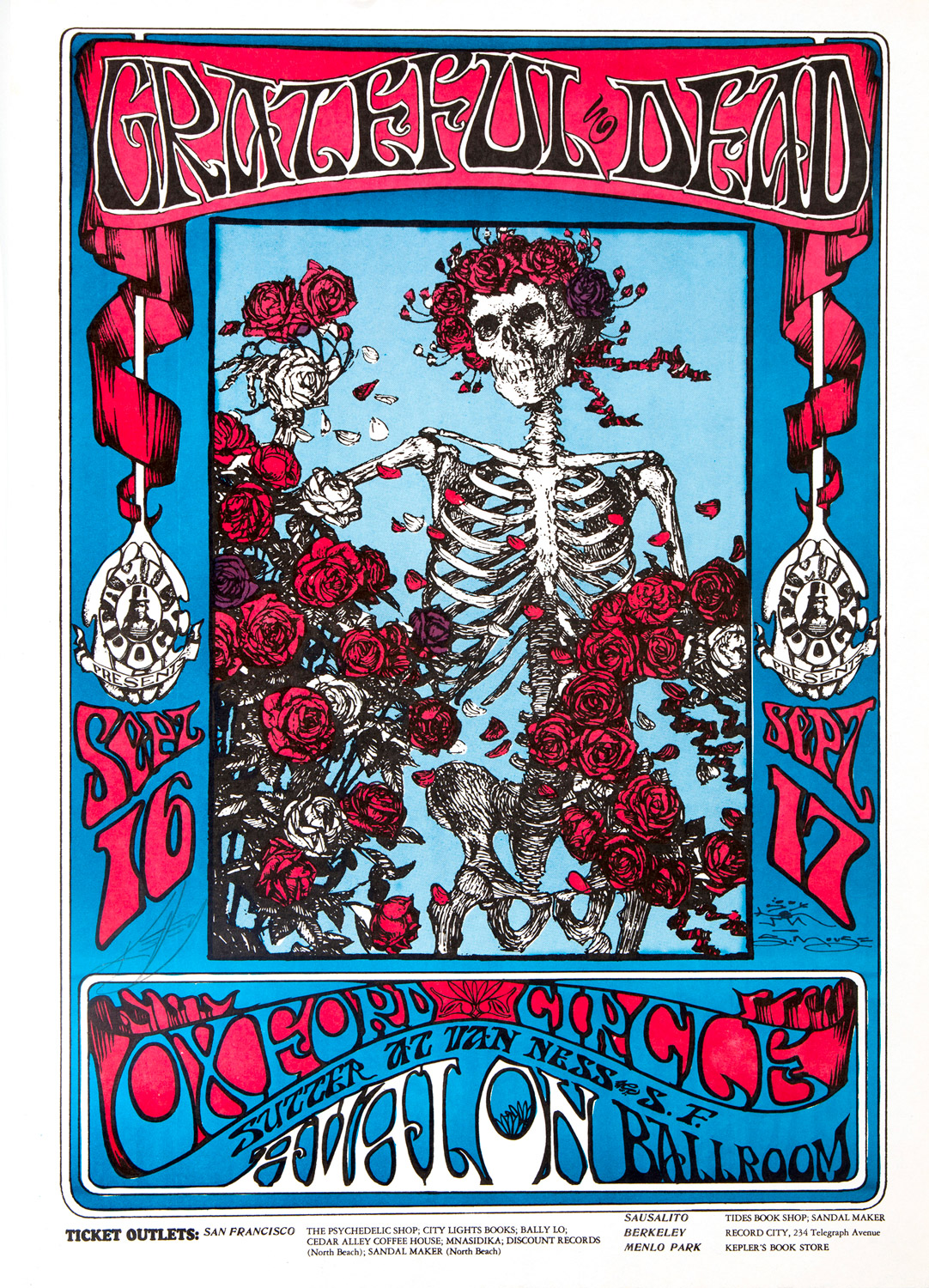

Among the works here is an iconic Grateful Dead poster — think skeleton and roses — done by Mouse and Kelley for a 1966 concert at the Avalon Ballroom. It’s displayed next to an example of one of the seven later forgeries of the same poster. So sought-after is the original work that a near-mint first-edition example went for $38,500 last year at an international psychedelic poster auction. Like much of the imagery used in psychedelic posters, the skeleton was appropriated; it was copied from British illustrator E.J. Sullivan, who was also influenced by Art Nouveau.

Westford worked for a time selling counter-culture-influenced clothing at a San Francisco boutique, and Behind the Beyond includes about 20 examples of 1960s fashion from his fashion collection: yards of bright print dresses, paper dresses and suede buckskin vests, displayed — a little eerily, for me — on mannequins. Wait, I found myself thinking: Didn’t my first girlfriend own that paisley sundress?

In a small darkened gallery upstairs, you can enjoy an intense sampling of black-light posters from Westford’s collection that are illuminated by the best black lights you may ever see.

Turned On: The American Blacklight Poster, 1967-71, one of two small accompanying exhibits, runs through July 16. Certainly no one I knew in the 1960s had black lights of this caliber. The posters glow so bright I looked closely at them and still had to check in with Westford to be sure I wasn’t really looking at high-def digital screens.

All of which brings up the question of drugs. “Do you have to be high to fully appreciate this show?” I asked.

Westford hesitated just slightly.

“If you came into this gallery under the influence, you’d have an elevated state of awareness that might enhance the exhibition,” he said, choosing his words carefully. “Well, I’m not advocating that you come to the museum stoned …”

Enlarge

That also brings up an art history issue. Counterculture art hasn’t always been taken seriously by the art establishment, certainly in large part because of this association with LSD and other psychoactive drugs.

Much more favorable attention has been focused on the comic books — think R. Crumb — that came out of the Bay Area of the 1960s than on these brightly mind-bending posters. One reason may be that counter-culture comic books continued to develop, eventually finding respectability under the name “graphic novels,” while psychedelic posters, with their druggie associations, were limited to a small geographic region during a small slice of time, from the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 to the closing of Fillmore West in 1971.

East Coast parochialism was also a factor. Created thousands of miles from the art capital of New York City, and essentially spent within about five years, psychedelic poster art was easily ignored by experts — even though there are strong connections between the posters in this show and the high-brow Pop artists working in New York in those days such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and Op artists such as Joseph Albers.

A small exhibition of prints upstairs in the Hallie Ford’s print room, The 60s: Pop and Op Art Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, provides that broader context through Oct. 22.

Finally, isn’t all this Summer of Love reflection just a bit precious?

Maybe so, especially if you don’t happen to be a Baby Boomer. A similar, if larger, poster show is running through Aug. 20 at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll includes 26 posters from Westford’s collection, selected from 56 he donated to the museum last year.

The de Young show drew this pointed review from critics Emma Silvers and Sarah Hotchkiss at KQED:

Let’s get one thing out of the way: We are not convinced any of this summer’s grand re-telling is necessary. As California natives in our early 30s, we’ve grown up in the persistent shadow of the Summer of Love, a specter of San Francisco in the sixties as sacred text — the prophets Jerry Garcia, Ken Kesey and Bill Graham untouchable in their retroactive glory….

Can we discuss what came after? What bands they influenced, or even what they stood for? Where can their nonconformist message still be felt in present-day San Francisco, where capitalism run amok has made it difficult if not impossible for artists to survive? Put bluntly: Why are we still talking about this?

Why, indeed?

I loved seeing Westford’s posters at the Hallie Ford. But I’m a Boomer, an old fart who still listens to Jimi and Janis and Jefferson Airplane. Much of my response to the show was visceral and emotional, that sense of comfortable recognition you get from revisiting an interesting old friend.

That said, the Hallie Ford show does a good job of presenting the work in an art-historical context. I don’t imagine many people with an interest in visual art would fail to find it interesting, however old they might be.

But the question remains: Can Boomers trust anybody under 30?

Westford has his own feelings on the new generation gap.

“If the only people who come to see this show are old hippies, I’ve failed,” he says.