According to Lorenzo “Rennie” Harris, the three laws of hip-hop culture are “innovation, individuality and creativity.”

“Hip hop comes from the word ‘hippie,’ which means to either open your eyes or re-open your eyes — to be aware,” Harris says.

Kickstarted in the South Bronx as early as ’72 — at jams in parks, schools, community centers and clubs — and led by DJ Clive “Kool Herc” Campbell, Afrika Bambaataa and Pete DJ Jones, the global phenomenon we’ve come to appreciate as hip hop has many progenitors, each adding his or her own original spin to graffiti, deejaying, b-boying and emceeing.

Harris is one of them.

Harris founded his dance company, Rennie Harris Puremovement, in 1992, and in ’96 I spent a week driving Harris and his entourage to outreach events around Seattle. Twenty years later, it’s fun to catch up with him by phone all the way from Japan, where he’s currently in artistic residence.

He’s received many honors, including a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship, a slew of grants from the Ford Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Pew Charitable Trust and the National Dance Project. Harris has also been named a creative ambassador, and given the key to the city for his hometown of Philadelphia.

In North Philly at age 12, Harris and a buddy entered — and won — a church talent show. And Harris kept dancing. Forming troupes in his teens, he was soon opening for a venerable who’s who of hip hop: Salt-n-Pepa, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Doug E. Fresh, Run DMC, Sugar Hill Gang, Kurtis Blow and more.

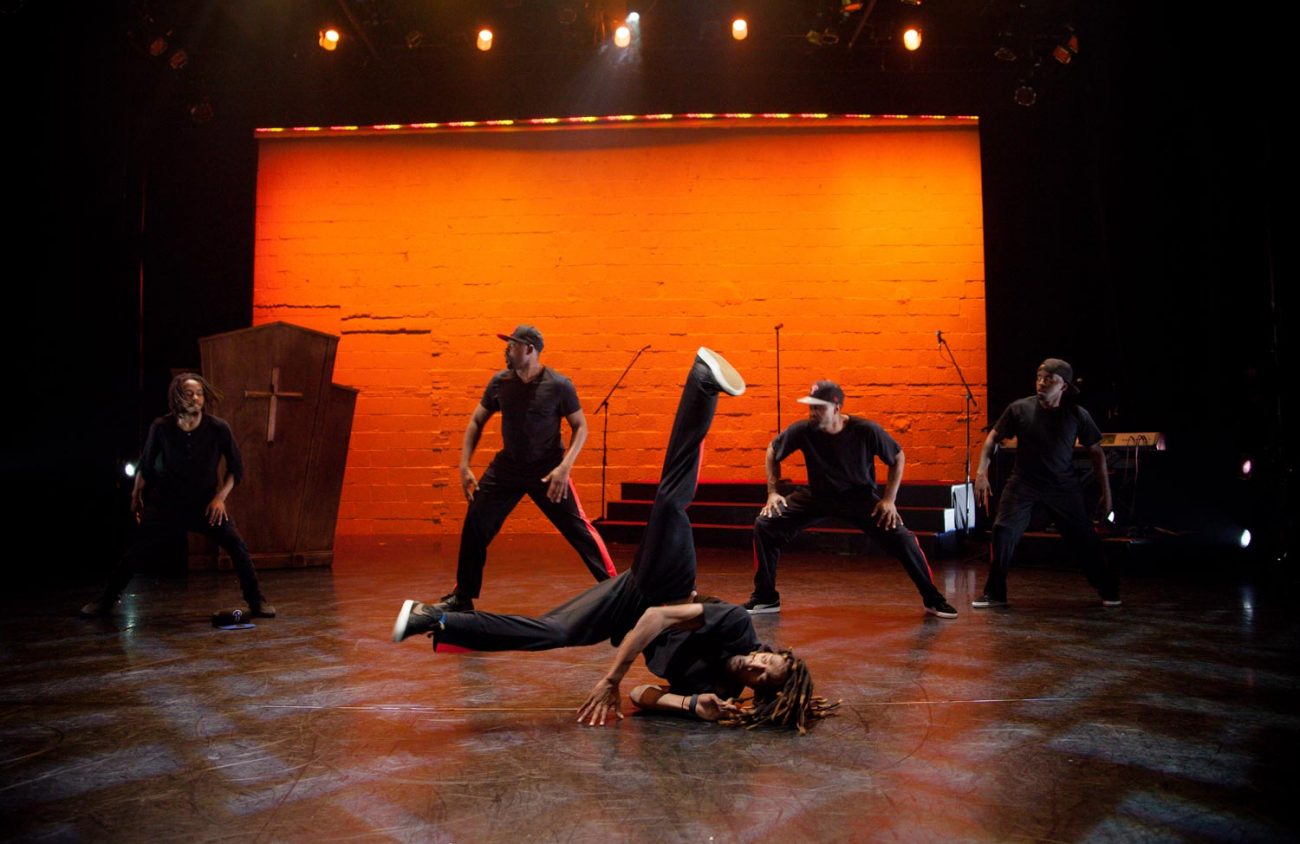

This season Harris brings his latest work, Lifted!, to Portland’s Whitebird Dance, and the show features a live choir singing gospel and house music.

“I always wanted to do a live choir — I love gospel-house,” Harris says. “And I thought it would be cool to actually create a work that not only had the music, but had the singers there to sing it.”

Harris would likely shrug off the praise, but it’s humbling to speak to a living legend.

Hip-hop culture had been snapped up by Madison Avenue and Hollywood by the mid-1980s, but Harris pinpoints ’81 as the year the form broke wide.

Sally Banes’ influential Village Voice piece, “Physical Graffiti: Breaking Is Hard to Do,” in March 1981 — featuring Martha Cooper’s photos of breaking and b-boys — exposed New Yorkers, and soon the world, to what had already been a thriving and multidimensional cultural scene.

The first print article to mention “hip-hop culture” by name was published in the East Village Eye in January 1982, featuring an interview with disc jockey and singer-songwriter Afrika Bambaataa.

“The writer asked Bambaataa to explain what they were doing,” Harris recalls. “And he said, ‘We’re not doing anything, we’re just hip-hopping around.’”

In that same article Bambaataa refers to hip-hop dance as an alternative to the physical fighting, or “jitterbugging” — as he calls it — between warring South Bronx gang members.

“It’s innate to humans to be creative,” Harris says. “When resources are scarce, we then become creative about how we’re going to voice our opinion, how we’re going to survive. Without fear, we don’t survive. It’s the foundation of humanity. Fear is the catalyst for all of it.”

The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates says that, in America, it’s traditional to destroy the black body — that it’s our American heritage. So what is the role of black dance in the face of that reality?

“Dance plays the same role it’s always played — since the beginning of time — and that is communion with something higher than yourself, or a higher being,” Harris says.

“We’re doing what we do,” he continues. “It’s not as if dance is going to say something new for this generation than for another generation or the generation before it. Without movement, you die.”

Ask most “dance people” to tell you about black dance, and they’d mention Dance Theatre of Harlem, Alvin Ailey, maybe Katherine Dunham or Baba Chuck …

“But those things aren’t black dance,” Harris says. “Those are black people doing white dance. Black dance is social dance, movement that was handed down from generation to generation — since slavery. That’s black dance.”

“Anything that comes out of the African American Community is black dance,” Harris says. “The other stuff is black folk doing Western dance. It doesn’t make it black just because they’re doing ballet and they’re black.”

Think tap dancing, swing, lindy, stepping — or community dances of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. Harris notes that these forms have been routinely appropriated — or stolen.

“I wouldn’t use ‘appropriation’ — I’d call it cultural theft,” he says. “That’s basically what it is and I think we’re too light with our words. And it’s been theft since we got here. I mean, we were stolen. And we got placed here in America and the stealing kept happening.”

This isn’t a new process.

“On the plantation, they imitated blacks. And since then, this has been going on,” Harris says. “The imitation of the black body — from Venus Hottentot — to the bustle of white women wearing those dresses extending their derrieres, right? We were stolen and everything is usurping, taking from that culture, from day one.”

Harris notes that this is not even European land, but land that was taken from its indigenous residents.

“When you don’t acknowledge where something comes from, or how it came about, you’re eradicating the idea that it even came from another culture — you’re just wiping that slate clean,” Harris says.

“The white kids walking around with hip-hop gear, they have no clue who Spoonie Gee is, they have no clue who DJ Cassanova is or who MC Caz is, right?” Harris asks. “So now you have successfully wiped the memory of a particular culture and their contributions. And you could say that for a lot of other cultures here as well, not just African-American culture.”

Then Harris says something that stops me in my tracks.

“At the end of the day, I don’t see myself as an artist,” Harris says. “I see myself as a human. To say that you’re an ‘artist’ — they’ll put a fucking label on you and put you up on the shelf. And then people treat you a certain way — and that’s the issue.”

He continues: “I never sought to be a choreographer — wasn’t my plan. Wasn’t trying to be a dancer — wasn’t my plan. It was a means to an end economically. It gave me some money, and I danced and I just kept going. And I became this ‘choreographer.’ But I don’t like the choreography that I do. I don’t like any of the work that I do — I think all of it is shit and bullshit. I think the whole field is full of shit.

“But what I realized by doing what I do, is it became clear that I was touching people in their lives — and that was the reason that I stayed in.”

Harris relates American black dance back to its subjugated origins, and points out the razor’s edge between “success” and selling out.

He says he’s disbanded his company three times in 25 years, “because I thought this was the most evil business of them all — to enter and then contain someone, i.e. ‘entertainment.’ Once I figured that out, I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t really want to be a part of this.’”

But Harris and his 25-year-old company persist, touring internationally, offering workshops and performances around the globe.

“If you want to speak to someone, don’t use language. And specifically, don’t use the English language to say anything to anyone,” Harris says. “Movement is the first language. Ninety-eight percent of our communication comes from body language.”

“You know a person loves you not because the person tells you they love you — that’s our own vanity,” he adds. “You know that person loves you because when they went into the kitchen they got themselves a glass of water and they brought you a glass of water, too.”

Enlarge

Photo courtesy Brian Mengini

Harris relates body language from love, back to fear and, finally, to violence.

“There are actions that we understand, that we communicate,” he says. “Think about it: How would you move slaves onto a ship? No one spoke the language. The Europeans went in and, without any help from Africans, actually started to capture Africans. How did that come about?

He continues that it was through the body language of those particular people who sensed fear in Africans. Either Africans went into flight, or they gave in. “This was done through body language and energy,” Harris says.

The onslaught of recent media images of bodies engaged in political, economic and social unrest communicates volumes. We’re inundated with raw emotion — a kind of trauma. Too often we see and are desensitized to the routine destruction of the black body.

Yet Harris’s dance company — one of the only performance groups of its kind on the planet — still faces a steep challenge when they ask audiences to explore deeper artistic themes that might confront our current social climate.

“If anything, it’s like the 1970s, 1980s here in the States,” he says. “Everyone else outside of the U.S. has evolved on some level. In the U.S., we have become elitist about how we receive anything that’s considered hip-hop culture — or that comes from the street.”

Harris loops back to cultural theft.

“I think what it is when you take something from a culture and you don’t have the background of that culture, you’re interpreting what you think you’re seeing — that’s through your cultural lens,” he explains. “Audiences want to be entertained, to see people flipping, doing what I call the ‘Nova monkey’ dance of yesteryear.”

(The derogatory term “Nova monkey” refers to someone who’s trying to figure out how something works by swinging and banging it around — like a monkey on the PBS television programs Nova.)

“Economically, we can kind of get our feet going, get some traction, but we’re not able to evolve, because audiences aren’t evolving,” Harris says.

Harris notes that some hip-hop dance companies survive by fusing their work to a modern dance aesthetic, placating audiences with a product they understand, one built on “Western language — and therefore it’s elevated, as if one culture is higher than another one,” he says. “I’m not a fan of that, but it is what it is.”

“And then the other ones, they aren’t getting any help so that they can develop, so that they can move on and evolve,” Harris adds. “We’re in a catch-22. Audiences are not appreciating that we need to have support in order to develop the work and have a voice.”

Because dance, he explains, “has always been about the darkness and the light. Dance celebrates life. If the harvest comes, we dance. If someone dies, we dance. If someone is born, we dance,” Harris says.

“Dance is always about living.”

Rennie Harris Puremovement performs at 8pm Jan. 25-27, 2018, at Lincoln Hall, Portland State University, in Portland. For more information or for tickets, visit whitebird.org.