It’s not often the work of a 10-year-old artist winds up in a museum. The French child prodigy Jacques-Henri Lartigue is an exception, having been included in a variety of international exhibitions stretching back to the 1960s.

His photograph “Ma cousine Bichonnade” makes a nice entry point for the current show at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, En Noir Et Blanc: Early French Photography. The image shows the eponymous Bichonnade hovering down an outdoor staircase, the whimsical moment seized perfectly by her young cousin Lartigue.

In the neighboring photograph, “Avenue de Bois de Boulogne,” Lartigue turned his gaze to the public realm, capturing a Belle Époque madame on a stroll, her furs and dogs aligned perfectly with upturned nose. This one Lartigue shot in 1911 at the ripe old age of 16.

Two amazing photographs made by a kid! — both so guileless and natural you’d think any weekend snapshooter could take them. And maybe they could, for that’s the magic, and the curse, of photography in a nutshell. One can create a masterpiece with almost no training, but mastery is more elusive.

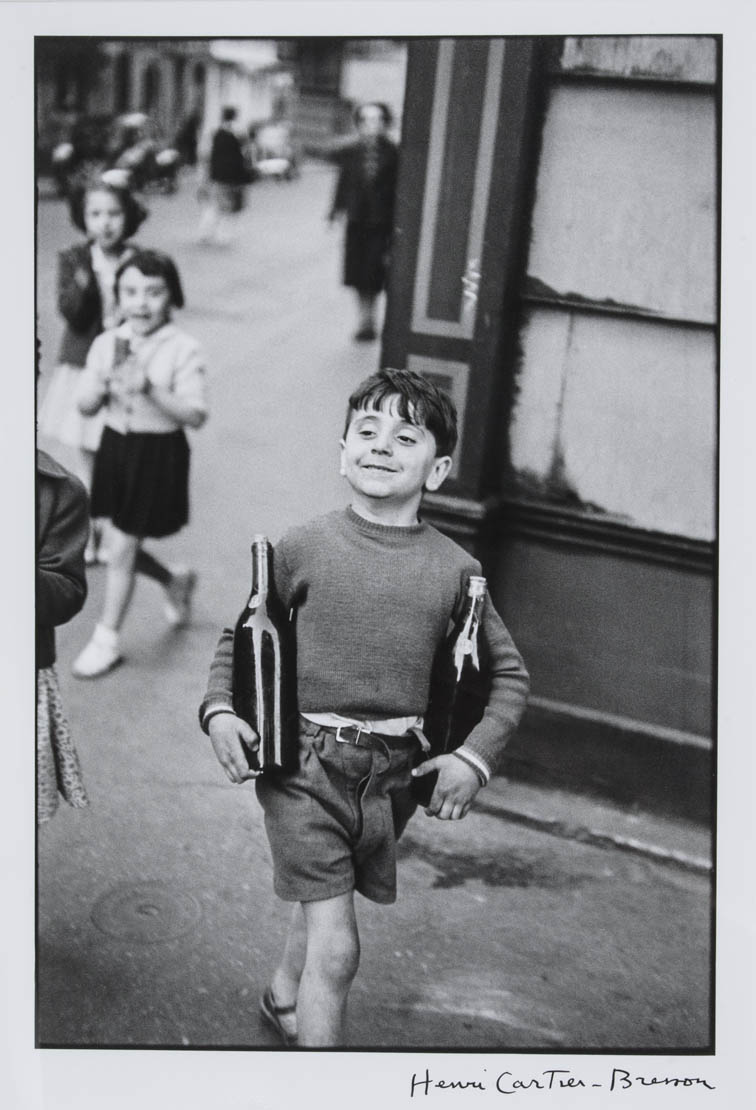

Which brings me to the photo on the room’s opposite end. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “Rue Mouffetard, Paris, 1954,” balances Lartigue’s youthful moxie with a photograph of youth itself. A beaming boy, by the looks of him roughly Lartigue’s age in 1905, carries two wine jugs around a street corner. The enormous bottles sit precariously in his small arms, and the proud moment is anxious with a sense of looming catastrophe. What happens next? It’s a delightfully ambiguous moment.

Whether this is childhood before the fall or just another street courier, Cartier-Bresson’s timing is impeccable. Of course, keen timing was his forte. As the wall captions note, his book Images à la Sauvette helped codify and popularize the significance of serendipity in street photography.

Alas, French law has since restricted the publication of candid moments, sweeping Cartier-Bresson’s era into the history books and onto the museum walls. “Rue Mouffetard” might roughly symbolize its high-water mark.

Enlarge

Cartier-Bresson and Lartigue notwithstanding, the bulk of En Noir Et Blanc is not public candids, but a mix of portraits and domestic interiors. Some photos blend both. Portraits by Man Ray, Brassaï and Doisneau offer an incisive glimpse of 20th-century French artistic life as practiced by, respectively, Man Ray, Picasso and the Isadores.

The backdrops of these photographs are as interesting as their putative subjects. A preoccupied Picasso is shadowed by the enormous chimney of his woodstove. Man Ray’s selfie shows off his Marcel Breuer chaise longue.

But the star of the show is a photo of the dining room of Raymond and Adrienne Isidore. Doisneau captures the couple gazing slyly from the corner of their homebuilt Picassiette in Chartres, framed by a mosaic tilework panel that would make Gaudi jealous.

Balancing the show’s straight photographs are a few experimental works. The restless Brassaï prefigured Photoshop by physically engraving his glass plates before printing them. His “Transmutations. IX: jeune fille rêvant” is the show’s most radical image, a tight blend of manipulation and lens-based imagery.

Even when shooting the so-called “real” world, Brassaï’s abstract leanings sometimes got the best of him. “Graffiti, tête de mort” reduces a human skull to an urban puncture wound. This caricature is taken from Brassaï’s larger series of wall carvings — a rough equivalent of “graffiti” in the era before spray paint. As with his Picasso portrait, the photo is printed slightly out of focus — perhaps an unconscious nod to abstraction? — not that it detracts in either case.

Enlarge

The show’s other experiments are by the American Dada/Surrealist Man Ray who, when he wasn’t relaxing on a Breuer chair, was a whir of Parisian creativity. “May Ray 1” tweaks expectations of visual representation with an image that looks like a collage but is, in fact, a photo of one.

Man Ray’s “Les Invendables,” a catalog from 1969, is even more abstract. It sits in a display case nearby, a few inscrutable page-spreads visible, its title a knowing tease to all working artists: “Unsellable.” “Why? Because the name is the only thing for sale. Without the signature the picture is worthless. You must take them both.” At least according to Man Ray.

On the museum wall, Man Ray’s question is rendered moot, since these photos are not on the market. In fact, most were donated by the late collector Dan Berley.

Combining them with contributions from George Wickes and Robert and Margaret Leary, En Noir Et Blanc’s curator Eric Dil has created a small powerhouse of an exhibition.

It’s a rare treat to see such a murderer’s row of luminaries on the wall anywhere, much less in little old Eugene. There’s enough variety to appeal to everyone from casual visitors to serious scholars.

Heck, even kids will like it. Bring your 10-year-old artist, or your inner 10-year-old. Let them see what peers have done. ▪

En Noir Et Blanc: Early French Photography is in the John and Ethel MacKinnon Gallery at JSMA through June 18.