The ancient Greeks called it peripeteia, the turning point in a classical tragedy that comes when the hero makes a decision that inevitably seals his fate.

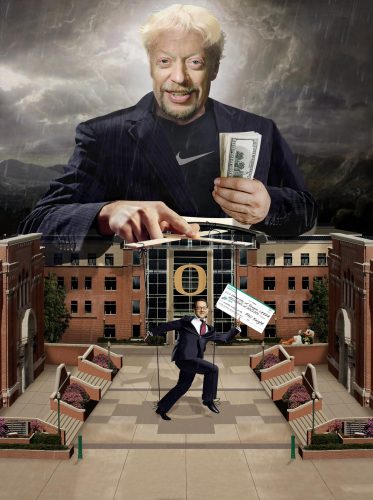

For the University of Oregon, peripeteia may have come in 2000, when then-UO President Dave Frohnmayer — a deeply honorable man struggling with the university’s funding crisis — sided with Nike’s founder, Phil Knight, in an international dispute over workers’ rights rather than backing students and faculty members who wanted the UO to support Nike’s workers.

In this tragic tale, Knight threatened to cut off millions in funding, both for the university and for a charity founded by Frohnmayer and his wife, when the university initially supported the Worker Rights Consortium, a group that was publicly attacking Nike for poor conditions in Asian sweatshops that produced its shoes.

And that tragic moment came when Frohnmayer quickly caved and withdrew university support for the rights group.

That is the tale told in a searing new book that comes out this week about corporate corruption at the University of Oregon.

University of Nike: How Corporate Cash Bought American Higher Education was written by Joshua Hunt, a former Oregonian who spent years researching the extent and depth of influence that Nike has gained over the UO through its millions of dollars in donations.

“I agree that ‘honorable’ is a word I would use to describe him,” Hunt says of Frohnmayer, who died in 2015. “He had a strict set of rules he tried his best to live by. He tended to enter into things with very good intentions.”

Hunt is talking by telephone from Tokyo, where he has lived since working there as a foreign correspondent for Reuters. “One reason [Frohnmayer’s] story is so attractive to a storyteller is it does have a lot of drama. You can see it very clearly, because there is such a track record … There is this large shadow he casts over Oregon’s history.”

In the hindsight of history, Frohnmayer, though honorable, may have been naïve.

While Frohnmayer was president of the UO, Knight — a UO graduate and major donor to the university — began giving $1 million a year to the tiny Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, a charity that Frohnmayer and his wife, Lynn, created to pay for research into the rare genetic disease that ultimately killed all three of their daughters over a 20-year period.

A donation from Knight was also adding $40,000 a year toward Frohnmayer’s UO salary, Hunt’s book says.

And Knight had pledged $30 million to the UO for the renovation of Autzen Stadium.

Perhaps it should have come as no surprise to anyone that Knight threatened to stop his donations when the university supported the Worker Rights Consortium.

Knight, Hunt writes, made it personal.

As 2000 came to a close, Hunt writes, “Knight made it clear that he would not be making his annual contribution to the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund. A dark, distressed mood fell over the Frohnmayer household, according to [family friend Arthur] Golden.”

Frohnmayer, Hunt writes, “suddenly realized he’d been laboring for years under some serious delusions about the nature of the bargain he’d made by taking Knight’s money.”

In a a statement emailed Oct. 16, Lynn Frohnmayer denies any of this happened. She says the book is “replete with a stunning array of errors, distortions, misrepresentations and outright falsehoods.” As an example, though, she challenges an account of a phone call between her and Knight — one that Hunt didn’t actually use in the book after hearing her denials.

In Hunt’s telling, under incredible financial pressure, Frohnmayer reversed his decision on the Worker Rights Consortium — and the Nike money came back.

That marked a turning point in the corruption of the UO, Hunt says.

Years down the line, he says, Nike’s influence would extend to a virtual wall of corporate silence surrounding the university and its doings. That wall is enforced, the book says, by an enormous public relations apparatus, sometimes working hand-in-hand with Nike employees, all striving to keep the public from knowing what the UO is really doing.

Basketball and Rape

The book got started because of an athletics scandal at the UO.

Hunt grew up, in part, in Oregon and has degrees in Japanese language and communication studies from Portland State University. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic and Bloomberg Businessweek, among other places.

In spring 2014, Hunt came to Eugene on assignment from The New York Times to investigate reports that a freshman student told police she’d been gang-raped by three UO basketball players. University administrators knew of the allegations the following day, Hunt writes in the introduction to his book, but kept the matter quiet and allowed the three men to play in that year’s NCAA basketball tournament.

Hunt was shocked at the bureaucratic wall of silence he encountered at the university.

“University administrators refused to talk with me, and occasionally locked themselves in their offices until I left the buildings where they worked,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “The players also refused to talk with me, while their lawyers insisted that the sex had been consensual. The school’s office of public records produced mostly useless, heavily redacted records concerning its handling of the incident, and even the school’s public relations professionals proved to be tight-lipped.”

It was the stunning resistance and obfuscation he met while pursuing the basketball story that inspired Hunt to write University of Nike.

“It became very clear early on that the university was doing a lot to prevent scrutiny of things that should be public records — archives and emails between university employees, things like that,” Hunt says. “That seemed like a very worthwhile story to tell.”

Hunt said his research convinced him that the UO was being run, at least in part, by its massive public relations department. “These people, it seemed, were preventing a close look at a lot of things that people in the campus community, whether they were professors or students or activists, were curious to learn about — because they suspected there was something wrong.”

The UO, he notes, has one public relations person for every 295 students.

That, he says in the book, totals “more than the combined faculty in Oregon’s departments of history, economics and philosophy.”

As Hunt worked on the basketball story, he says, he realized that the UO public relations staffers were often working with their corporate counterparts at Nike. “The focus was clearly on obfuscating the details of a violent crime until after the accused were finished competing in a basketball tournament,” he writes.

And so University of Nike was born.

“It began with that — a single issue — and a sense that there was a real lack of transparency. And a sense that the whole institution could benefit from a deeper look into what’s going on.”

The Financial Roots of the Problem

Hunt’s nearly 300-page book offers a detailed account of how the UO has, over decades of financial turmoil, gradually ceded control of a public institution to the boardroom at Nike.

The story begins with the taxpayer revolt of the 1980s that led Oregonians to pass Measure 5 in 1990. Still a problem for state and local government today, the new law drastically cut property taxes and, in the process, slashed public support for education across the state.

With state coffers drained by the need to replace school funding devastated by the measure, state funding for the UO plummeted from 50 percent of the university’s budget in 1989 to just 5 percent in 2013.

When he took over as president of the university in 1994, Frohnmayer knew he had to do something about the financial crisis.

At this point, in Hunt’s telling, nothing especially nefarious was happening.

“It was confluence, not conspiracy, that Knight went looking to invest in a university just as Oregon’s oldest and most prestigious institution of higher learning found itself in need of a wealthy benefactor,” he writes in the book.

But some evil seeds were being planted. The same political arch-conservatives who were busily cutting public education in Oregon were also giving Nike and other large corporations here a buffet of tax breaks. As tax support for the UO plummeted, Nike’s profits soared.

Perhaps because he’s a career journalist, Hunt has focused much of his attention in the book on the secrecy behind which the university operates — secrecy that he believes may violate Oregon public records law.

“There is a chapter that describes some potentially illegal practices — certainly bad faith practices, dishonest practices — by the public records department at the University of Oregon,” Hunt says of his book.

He’s talking about the university’s handling of the rape accusations against the basketball players. Lawyers for The New York Times argued in legal papers that the UO had, as he writes in the book, “demonstrated a willingness to ‘use privacy as both a sword and a shield’ in order to prevent public scrutiny of its handling of sexual assault on campus.”

“It’s one part of the book I’m very proud of,” Hunt says. “It’s helpful for journalists to know these things, because we often suspect them.”

Coming Soon: The Knight Campus

The most important point Hunt has to make, he says, is that this isn’t just about sports. Phil and Penny Knight are currently funding much of the cost of the new Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, a $1-billion project toward which the Knights have pledged $500 million.

“It’s much more than another fancy building with Knight’s name on it,” Hunt says. [The university already has the Knight Library, Matthew Knight Arena and William W. Knight Law Center, as well as a number of buildings not named for the family.] “It’s a serious opportunity for the further corruption of a once-great institution. There is no other way to look at it.”

In the book, Hunt argues that corporate corruption of American education began after World War II with government-funded secret research conducted for the Central Intelligence Agency. “America’s universities,” he writes, “proved themselves willing to do virtually anything for money, especially when they were allowed to operate in the shadows.”

Very quickly, he argues, the work turned into such abhorrent projects as MK-Ultra, which explored torture techniques on human subjects and resulted in the CIA’s manual for interrogation and torture. Moving ahead into the 1960s, federal money paid for secret research on everything from biological weapons to the effects of radioactivity.

In the late 1960s tobacco companies entered the picture. Faced with growing evidence of the harm caused by cigarette smoking, the tobacco industry began buying university research on the effects of smoking in an effort to muddy the public picture. According to one scholar, industry-funded research on the effects of second-hand smoke, for example, was 90 percent more likely to find no harm than independent research. Funding channels were muddied as well to conceal the corporate sources of the money.

The Knights’ funding of the Knight Campus is a major red flag for Hunt, who fears that much research done there — for pharmaceutical companies, for example — will be hidden from public view.

“This is, once again, a very dangerous thing — perhaps the most dangerous thing,” he says. “There is at least a certain amount of skepticism about big-money athletics at colleges. To the extent that people look at the Knight Campus, though, they say ‘Look, here’s a billionaire giving money to academics for once!’ No. This is a great big loophole for transparency and accountability. We may never hear a thing about what goes on inside that Knight Campus.”

What’s to be Done?

Hunt says the problems he encountered at the UO are common at public universities around the country. He hopes his book, to be released by Melville House on Oct. 23, provokes a national conversation about stopping corporate corruption of education.

“I don’t think we can expect corporations to change,” he says. “We have to change them.”

The problems at the UO, he says, represent “the confluence of deeply conservative Republican ideology with neoliberal ideology and market worship.”

Solutions are most likely to come not from within the system but from what he calls “real activism.”

“We’ve seen that on the national stage with Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo movement. It’s hard to combat problems like this under the framework we have now, which suggests that the market solves everything and capitalism is always good.”

More broadly, he is calling for a change in the way people see their role as citizens.

“In my lifetime, Oregonians have become much less accountable as citizens,” he says. “Too many Oregonians have come to think of themselves merely as taxpayers, not as citizens. We need to start thinking of ourselves as deeply connected to our public institutions, and we need to start thinking of our public institutions — especially public universities — as deeply connected to our prospects for success.”

Joshua Hunt will talk at a book-launch event for University of Nike (Melville House, $27.99) from 7 to 9 pm Tuesday, Oct. 23, at Tsunami Books. Free.

UO Mum on University of Nike

But public relations staffer gushes about Phil Knight’s generosity

Eugene Weekly sent University of Oregon President Michael Schill — who regularly pledges transparency from his administration — a few specific questions about Joshua Hunt’s book University of Nike.

The list included questions such as these:

In what ways does the generosity of Phil Knight and Nike give them influence over the University of Oregon?

How would you describe the nature of that influence?

What can be done to restore public confidence that the UO is fully accountable to the citizens of Oregon?

What can be done to restore public funding to education in Oregon?

Will there be any limitations on secret research done at the Knight Campus?

Schill declined to answer any of the questions we sent.

Instead, the UO made its official response to the book in a brief statement emailed by Kyle Henley, the university’s vice president for communications: “Given our focus on the university’s future, we will not engage in debate over Mr. Hunt’s book, which largely speculates about and rehashes historical events that have been covered elsewhere.”

Old news, in other words.

Henley’s statement did go on at some length about Nike’s “generous support” of the university.

“The University of Oregon is the birthplace of Nike, and we are extremely grateful to both Nike as a company and to Phil and Penny Knight individually for their generous support of this university over many decades, as well as their support of other academic institutions and vital causes in Oregon and beyond,” the statement said.

“The Knights care deeply about education, health care, sports and so much more, and they are unquestionably the most generous philanthropists in our state’s history. Their support for both academic and athletic programs at University of Oregon comes without strings attached and has transformed this campus in profoundly positive ways. The state of Oregon, our citizenry and this institution are all better for it.” — Bob Keefer

A Note From the Publisher

Dear Readers,

The last two years have been some of the hardest in Eugene Weekly’s 43 years. There were moments when keeping the paper alive felt uncertain. And yet, here we are — still publishing, still investigating, still showing up every week.

That’s because of you!

Not just because of financial support (though that matters enormously), but because of the emails, notes, conversations, encouragement and ideas you shared along the way. You reminded us why this paper exists and who it’s for.

Listening to readers has always been at the heart of Eugene Weekly. This year, that meant launching our popular weekly Activist Alert column, after many of you told us there was no single, reliable place to find information about rallies, meetings and ways to get involved. You asked. We responded.

We’ve also continued to deepen the coverage that sets Eugene Weekly apart, including our in-depth reporting on local real estate development through Bricks & Mortar — digging into what’s being built, who’s behind it and how those decisions shape our community.

And, of course, we’ve continued to bring you the stories and features many of you depend on: investigations and local government reporting, arts and culture coverage, sudoku and crossword puzzles, Savage Love, and our extensive community events calendar. We feature award-winning stories by University of Oregon student reporters getting real world journalism experience. All free. In print and online.

None of this happens by accident. It happens because readers step up and say: this matters.

As we head into a new year, please consider supporting Eugene Weekly if you’re able. Every dollar helps keep us digging, questioning, celebrating — and yes, occasionally annoying exactly the right people. We consider that a public service.

Thank you for standing with us!

Publisher

Eugene Weekly

P.S. If you’d like to talk about supporting EW, I’d love to hear from you!

jody@eugeneweekly.com

(541) 484-0519