Art displayed at museums is organized by theme and framed by a curator’s or artist’s statement. The shows at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art are no exception, except for the Masterworks on Loan.

These works are part of a continually revolving lineup lent to the museum by private collectors. No theme ties them together except for their status as masterworks — and the possibility that works shown at the same time may be owned by the same anonymous collectors.

When I go to the JSMA, I never leave without checking out the walls in the halls where the masterworks are shown. I like that I never know what I’m going to find.

Of course, images of the borrowed masterworks are posted on the museum’s website. That will probably not change my viewing habits. Checking them out in person is an adventure, like going to a comedy club and not being familiar with the lineup.

Will I recognize any of the artists? And if I do, will I know the particular, often lesser-known work (or routine)?

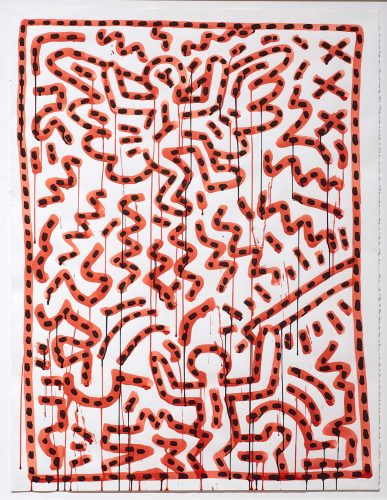

You always have the potential of a thrilling surprise — a really famous artist showing up (a common occurrence at comedy clubs, especially in New York and L.A.), which is how I felt on seeing Jean Dubuffet’s acrylic on canvas Symbiose (1980-81) beside Keith Haring’s Untitled (1982) acrylic on paper at the JSMA.

Dubuffet (1901-1985) studied art in Paris in 1918. Like other artists of his generation he rejected traditional notions of beauty. He equated technique with superficiality and replaced it with an appreciation of “low art” — Art Brut — believing images made by the untrained, such as children, were raw and therefore pure.

Symbiose’s childlike figure drawings might not seem controversial now, but critics first saw Dubuffet’s art as ugly and crude.

Keith Haring (1958-1990) studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Like Dubuffet, he rejected tradition — in his case, the tradition that art should be exclusively exhibited in a fine-art venue.

Miranda Callander, the museum’s Masterworks on Loan manager, says it’s no accident these two works hang together.

“Haring studied Dubuffet and found striking similarities in their abstractions,” she says.

The paintings are similar. Both depict figures in an abstract format that is not representative of real space. Haring’s may seem more familiar, since his work has flowed easily between popular culture and fine art venues.

I first saw Haring’s work in the lowest of low places — underground in a New York subway station. Waiting for my train after work I stared straight ahead, the way one does in the subway (to avoid what’s on the ground), and that’s when a picture of a man with a television for a head caught my eye.

White lines drawn on the black space usually filled with advertising posters or graffiti — I remembered it because it wasn’t an ad and not exactly graffiti either. A few years later, when I was working at an art publication and Haring’s work was getting attention in a gallery, I overheard a conversation about someone ripping a door off in order to get the picture Haring had drawn.

Haring died in 1990 from complications related to HIV/AIDS. The entirety of his work — including the subway drawings, merchandise, collaborations, and more than 50 public artworks worldwide — was produced mostly in the 1980s when Haring was in his 20s.

Dubuffet didn’t get seriously started as an artist until his 40s. His philosophy about Art Brut (also called Raw Art) is often pointed to as the origin of Outsider Art. Haring is associated with such artists as his friend Jean-Michel Basquiat for helping to bring about the genre known as Street Art.

Seeing artwork in the Masterworks on Loan, without statement or introduction, you’ll be viewing it, to some extent, the way I first saw Haring’s work. Without introduction or framing device — except for that of the museum — you’ll be on your own to make of it what you will.

Symbiotic and Untitled are on view in the Focus Gallery at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art through Jan. 6.