If the powers behind the Jordan Cove Energy Project have their way, a large fracked-gas shipping hub will be sitting on the shores of Coos Bay on the Oregon Coast. But for nearly as long as the project has been in existence, environmentalists and concerned citizens have been resisting it.

The project is currently in a comment period for a state removal-fill permit as well as under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) review. Its opponents are pointing to concerns from the Federal Aviation Administration about the height of some of its structures.

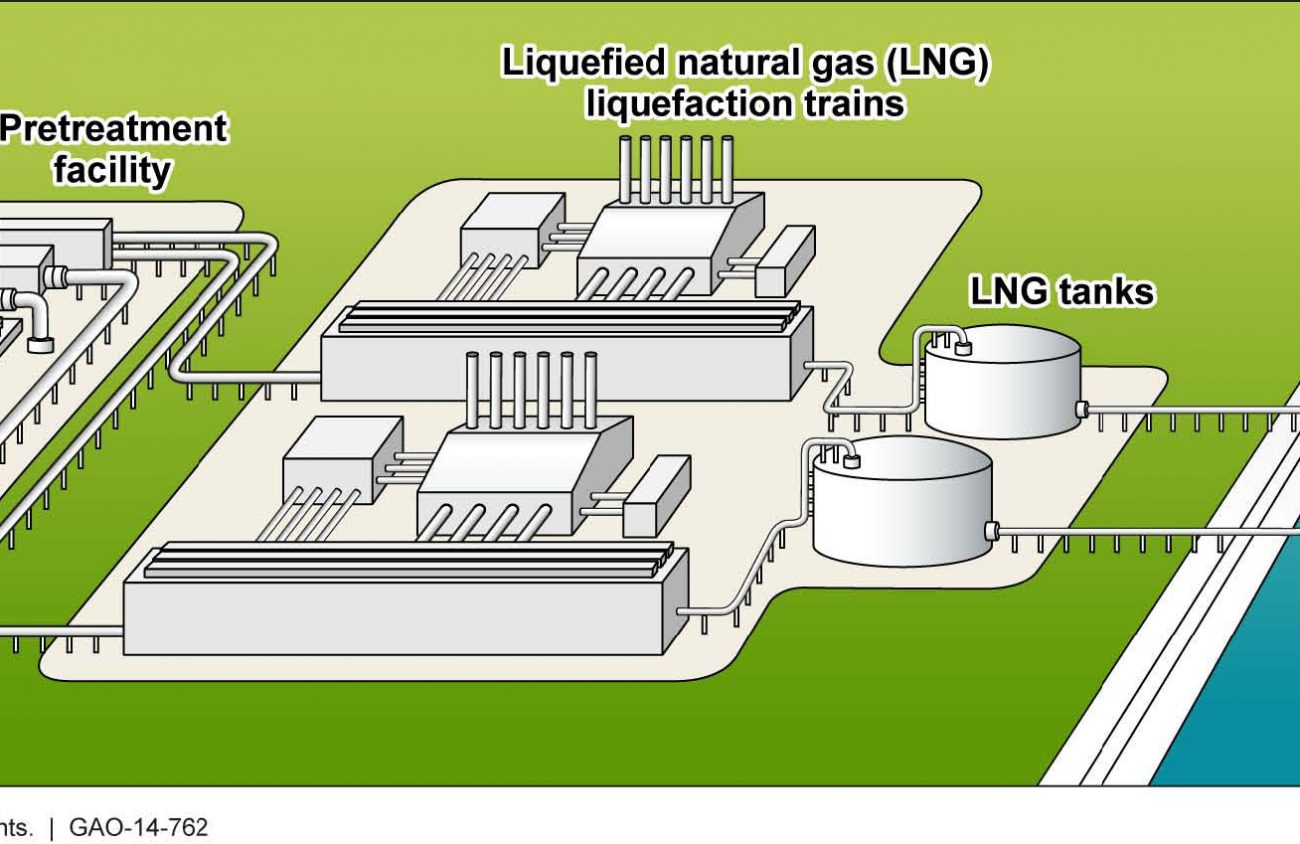

Jordan Cove as a project isn’t just a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal. It’s also a slip and access channel in the ocean as well as a more than 200-mile natural gas pipeline that would wind across southern Oregon. All three aspects of the project are addressed in the Department of State Lands (DSL) removal-fill permit. Jordan Cove would get the fracked gas via the Pacific Connector Pipeline, use cryogenic refrigeration to cool it and then export it on ocean-going ships.

Many thought the controversial proposal was tanked back in 2016 when FERC voted unanimously to deny approval.

But in 2017 the Trump administration called for the project’s return, and Veresen, the previous backer for the project, was purchased by Pembina, which is now pushing for the fracked-gas facility in Oregon.

The proposed terminal itself is in close proximity to Southwest Oregon Regional Airport in North Bend, something that has raised red flags for the FAA and opponents alike. Jody McCaffree, a member of Citizens for Renewables, says she’s had concerns about Jordan Cove since it was first raised as a possibility back in 2004.

“I can’t believe someone would be so crazy to propose a facility where they are proposing it,” McCaffree says, adding, “for one thing the airport is right there.”

Digging around in Jordan Cove’s filing documents, McCaffree found the FAA had sent Jordan Cove 13 notices “of presumed hazard” in May, addressing concerns with vessels and LNG gas processing towers in the airport’s airspace. The FAA states that Jordan Cove could either lower the heights or terminate its proposal.

Eugene Weekly has reached out to the FAA for comment.

The documents say the FAA’s study indicates “that the structure as described exceeds obstruction standards and/or would have an adverse physical or electromagnetic interference effect upon navigable airspace or air navigation facilities.” It continues that, pending resolution of the issues, “the structure is presumed to be a hazard to air navigation.”

Jordan Cove and Pembina didn’t respond to a request for comment.

McCaffree says she is also concerned with thermal plumes from the facility affecting airline flights, tsunami-caused dangers and, finally, dangers to community members from hazardous burn zones.

She points to a hazard map for the tankers that shows a boundary in which “no one is expected to survive in this zone. Structures will self ignite just from the heat.”

The other boundaries indicate where people would get second-degree burns in 30 seconds and finally, in the third zone, “People are still at risk of burns if they don’t seek shelter but exposure time is longer than in Zone 2.”

The map shows residences in Zone 2 and multiple schools in Zone 3. This particular map addresses just the tankers — not the facility itself or the gas pipeline.

Sam Krop of Cascadia Wildlands says, “This pipeline is a climate issue and so affects the whole state.” Cascadia Wildlands has worked with landowners who object to the gas pipeline crossing their land. Krop says the LNG project will be “the biggest climate polluter in our state.”

Rep. Peter DeFazio references the 2005 Energy Policy Act, enacted shortly after the process for Jordan Cove began, which gives FERC the authority to grant eminent domain to pipeline companies. Jordan Cove was originally proposed as an import facility for natural gas before it was flipped to export.

DeFazio says: “I do not think a private, for-profit company should be able to condemn private property in order to build a pipeline through someone’s backyard. The U.S. Constitution limits the use of eminent domain to actions necessary for ‘public use.’”

Originally the hearings for public comment on the project were only in impacted counties, but Krop says DSL agreed to do an additional hearing in Salem.

Ali Hansen of DSL says that while the department doesn’t have a stance on Jordan Cove, it is “responsible for ensuring Oregon’s removal-fill law is followed to the letter” and that public comment is “crucial.” Hansen adds, “Issues related to air navigation hazards are outside DSL’s role.”

McCaffree says to those who argue that the project will bring needed jobs to Coos Bay, “I’m not against jobs or industries that are complementary” — she points to the area’s fishing and oyster industries.

“You don’t have to destroy those jobs to create jobs,” she says. “If you are going to do something, it needs to be where everything works together.”

To comment on the Jordan Cove proposal by email, letter, web or fax go to oregon.gov/dsl/WW/Pages/jordancove.aspx. The public hearing in Salem is 5:30 pm Tuesday, Jan. 15 at the Auditorium at the Oregon Department of Veterans Affairs, 700 Summer Street NE across the street from the State Lands building.

This story has been updated.