White Lotus Gallery titled its current exhibit “Crossing Cultures” to mediate expectations about subject matter. Li Tie may be Chinese-American, but his art falls heavily on the American side. His portraits are mostly of Native Americans, and the landscapes he paints are inspired by drives taken through rural areas in the region.

Tie has lived in Portland for nearly two decades and in the U.S. for almost 30 years. His vision of America is open, rural and spiritual. He identifies with traditions of Native Americans, he says, because of their spiritual relationship to earth and sky. His paintings of landscapes, resembling places you might see driving between Eugene and Portland, are imbued with a personal symbolic language.

A bird in flight stands for transience, a barn for residence, a road for the great beyond.

Tie’s artistic journey began at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, where students were trained in the style of realism, or social realism, the purpose being to accurately and heroically represent the ideology, workers and leaders of China.

And for a while that is what Tie did, scaling small sculptures to monumental size for outdoor spaces.

At the time, galleries were practically nonexistent in China, Tie says, and his first show lasted less than a day. He and another artist hung their artwork in a makeshift outdoor space. They fastened their art — Tie was making prints at the time — on wires strung between trees, and authorities requested the exhibit be shut down the same day it went up.

It must have been a welcome shift of affairs when Tie attended San Diego State University, where he earned his MFA. Art programs in the states encourage originality. They expect emerging artists to say something new with their art.

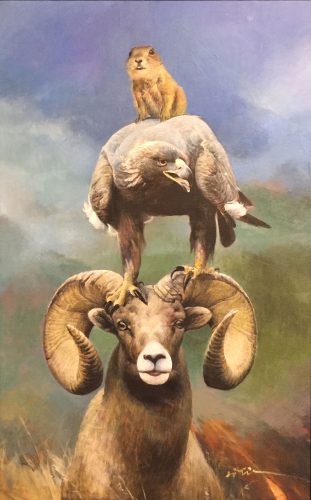

The paintings that say something most new to me in this exhibit are not landscapes or portraits, unless you consider representations of animals as portraits. The small handful of paintings of animals that hang in back of the gallery are among the most realistically executed, but what’s surprising is how the animals are posed, which is one on top of the other.

In one strange and almost comical painting, a bighorn sheep stares out at the viewer seemingly undisturbed as a hawk perches atop its horns.

Painting animals in a vertical format was inspired by the totem poles of the Northwest. “The animals represent spiritual beings that protect humans,” Tie says.

In rural villages in China, Tie says, a “go-between” is someone who carries messages between the earthly realm and the ones underneath or above. So the idea of spiritual beings is one with which he is familiar. His portraits and landscapes represent what the eye sees. His inspiration draws on this notion that spiritual realities exist alongside the ones we perceive with our eyes.

In Search of Lightning is a vibrant sunset painting. Yellow, orange and pink clouds hover above an expansive green field. A road takes you to the horizon where a lightning bolt bursts from the sky. On the road is a small boy with binoculars looking up. “A curious kid” Tie says, “trying to see impossible things.”

Aside from having been raised in China, and living in the U.S., Li Tie has traveled to Thailand, India, North Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia and Tibet. That he searches for inspiration these days closer to home, in the Pacific Northwest, doesn’t necessarily mean he’s done trying to see impossible things.

Unlike other artists, Tie doesn’t take pictures or make sketches when he’s on the road driving for inspiration. He likes to work without source material.

“I can be more free that way,” he says.

Li Tie’s exhibit Crossing Cultures is at White Lotus Gallery through Feb. 26.