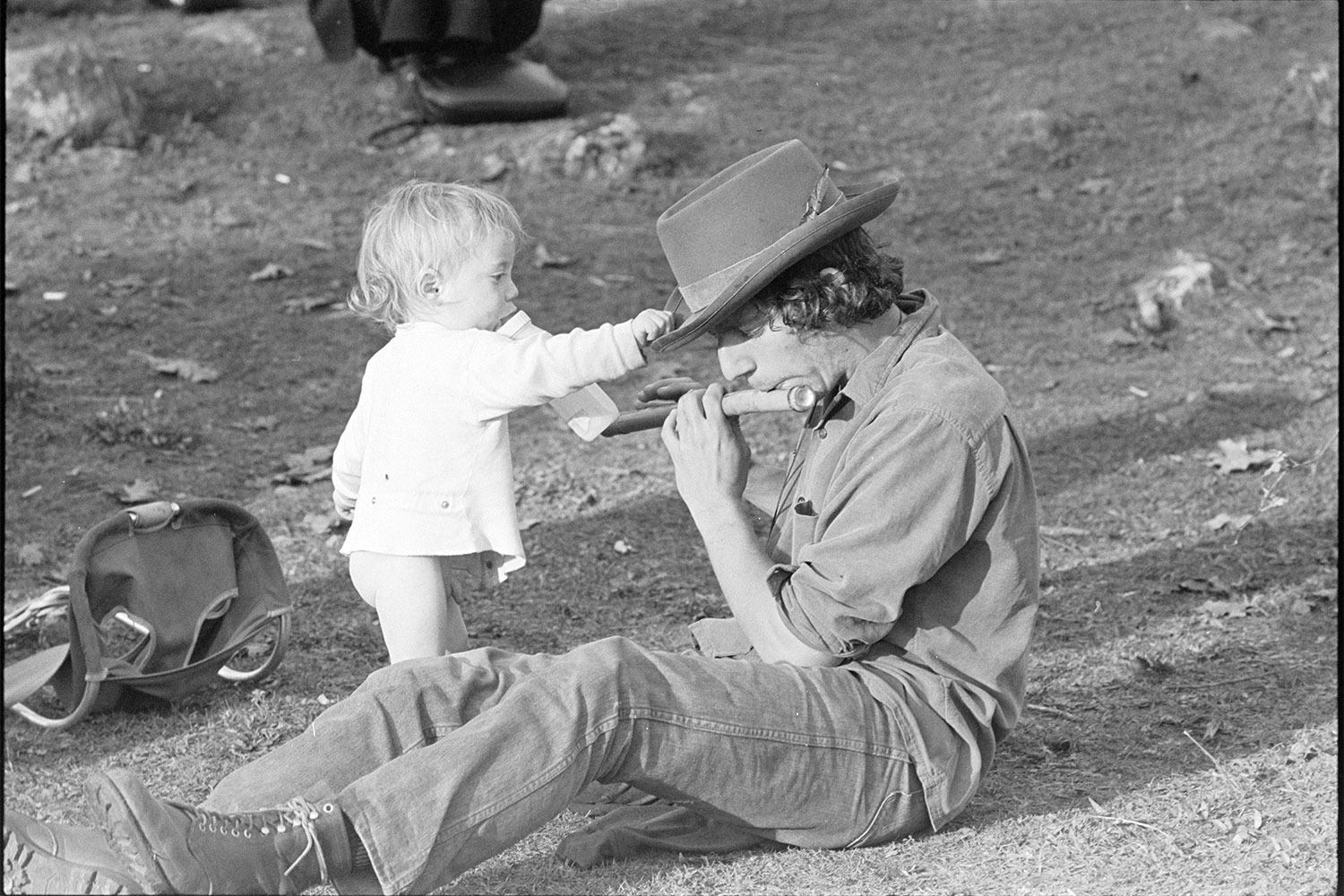

The raucous three-day arts and cultural extravaganza known today as the Oregon Country Fair began 50 years ago as a small crafts fair organized by parents and teachers to raise funds for an alternative school called Children’s House. Fittingly, Children’s House emphasized a child’s right to play.

Over the next five decades, the Oregon Country Fair would offer kids of all ages a place to frolic every year in its forests and meadows near Veneta, 15 miles west of Eugene. The Fair would expand exponentially from a few dozen volunteers making decisions by consensus in the 1970s, to an established nonprofit organization in 2019 with a 12-member board of directors, half a dozen full-time employees and thousands of volunteers serving on dozens of crews.

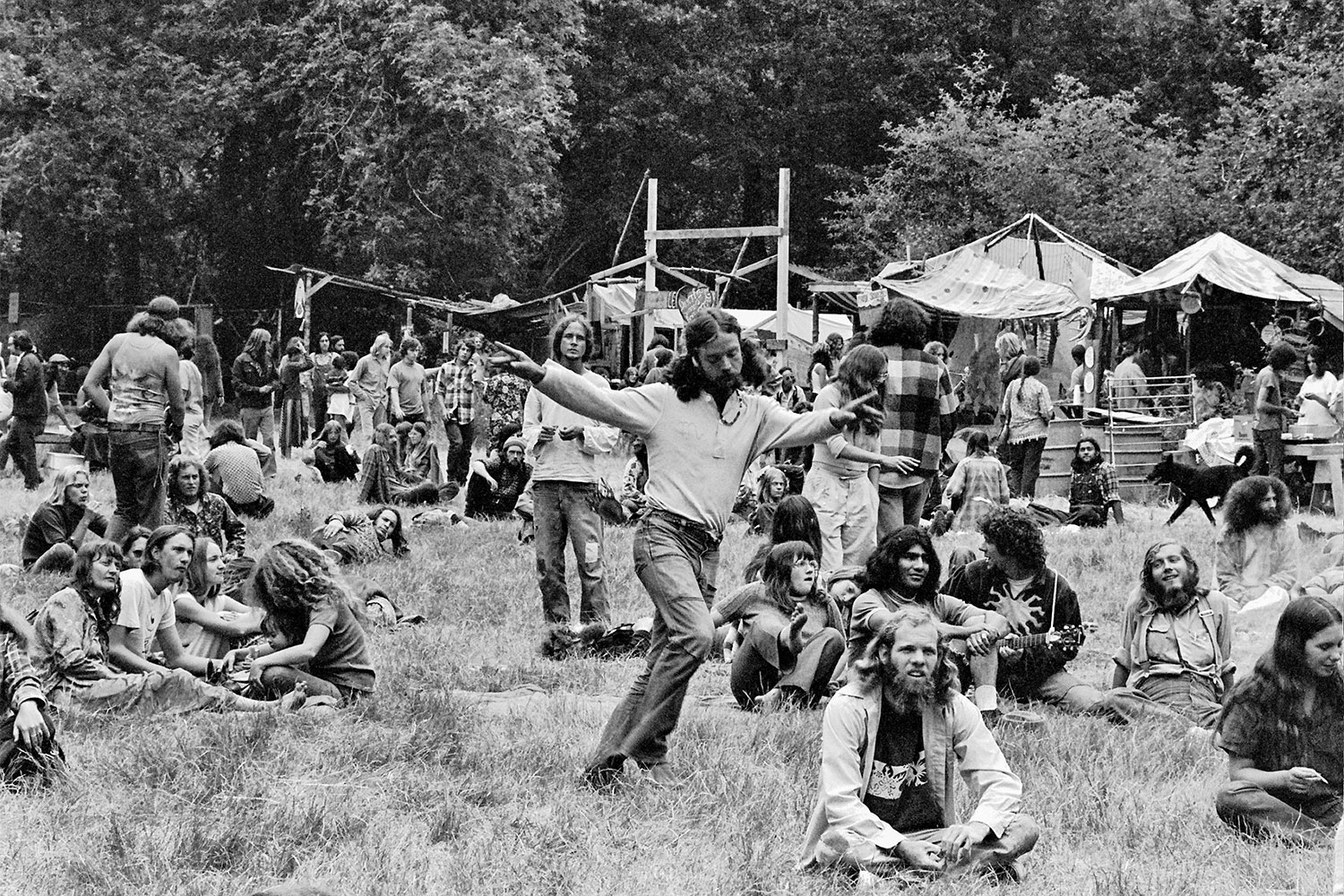

Born amid the turbulence and strife of the 1960s culture wars, each Fair created a weekend oasis of feisty fun, Earth awareness, group cooperation and individual respect. Today more than 45,000 Fairgoers annually flock to the Oregon Country Fair from the all over the world to immerse themselves in costumed revelry, unlimited music, delightful vaudeville entertainment and scrumptious food. Through it all, the Fair has remained true to its countercultural roots.

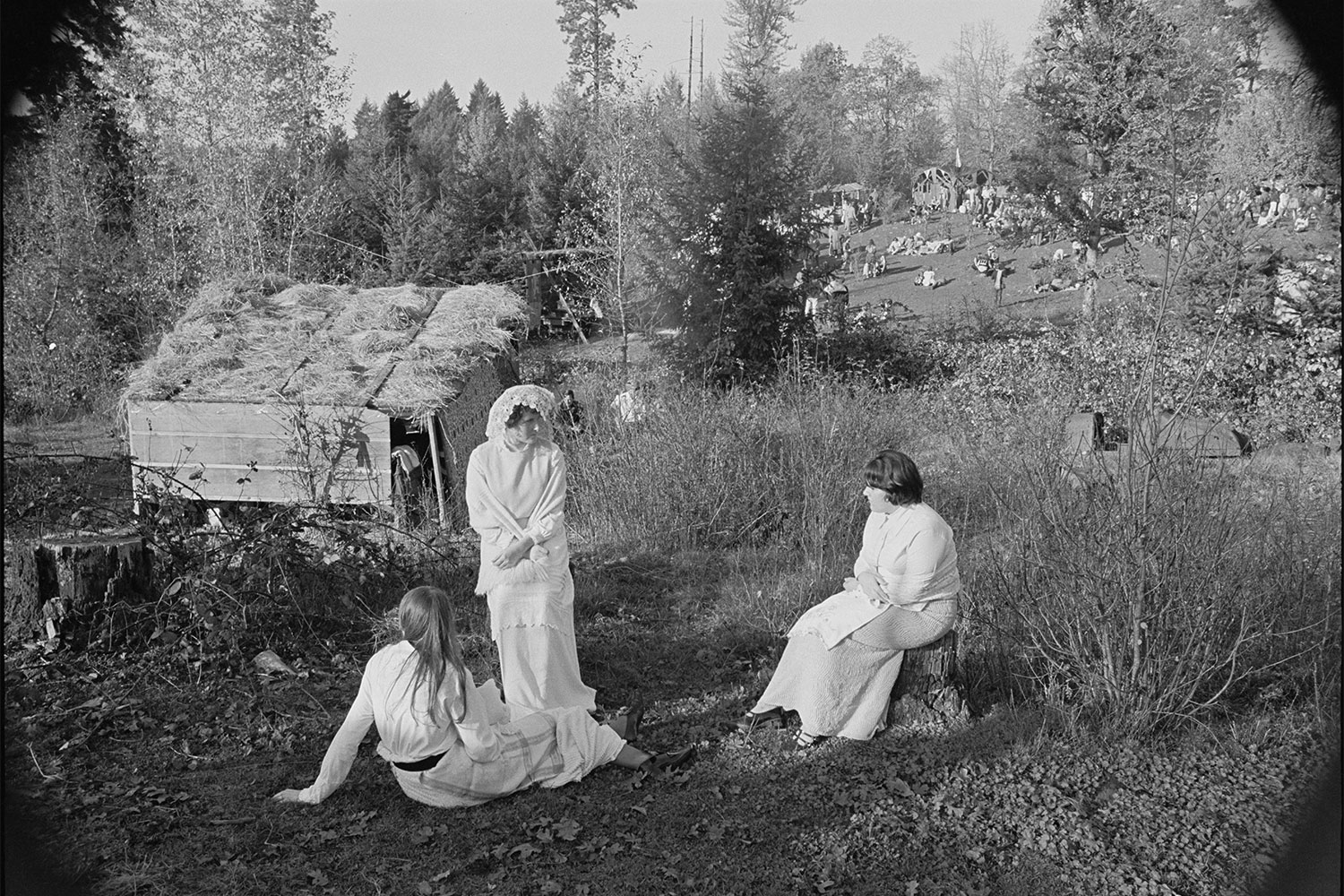

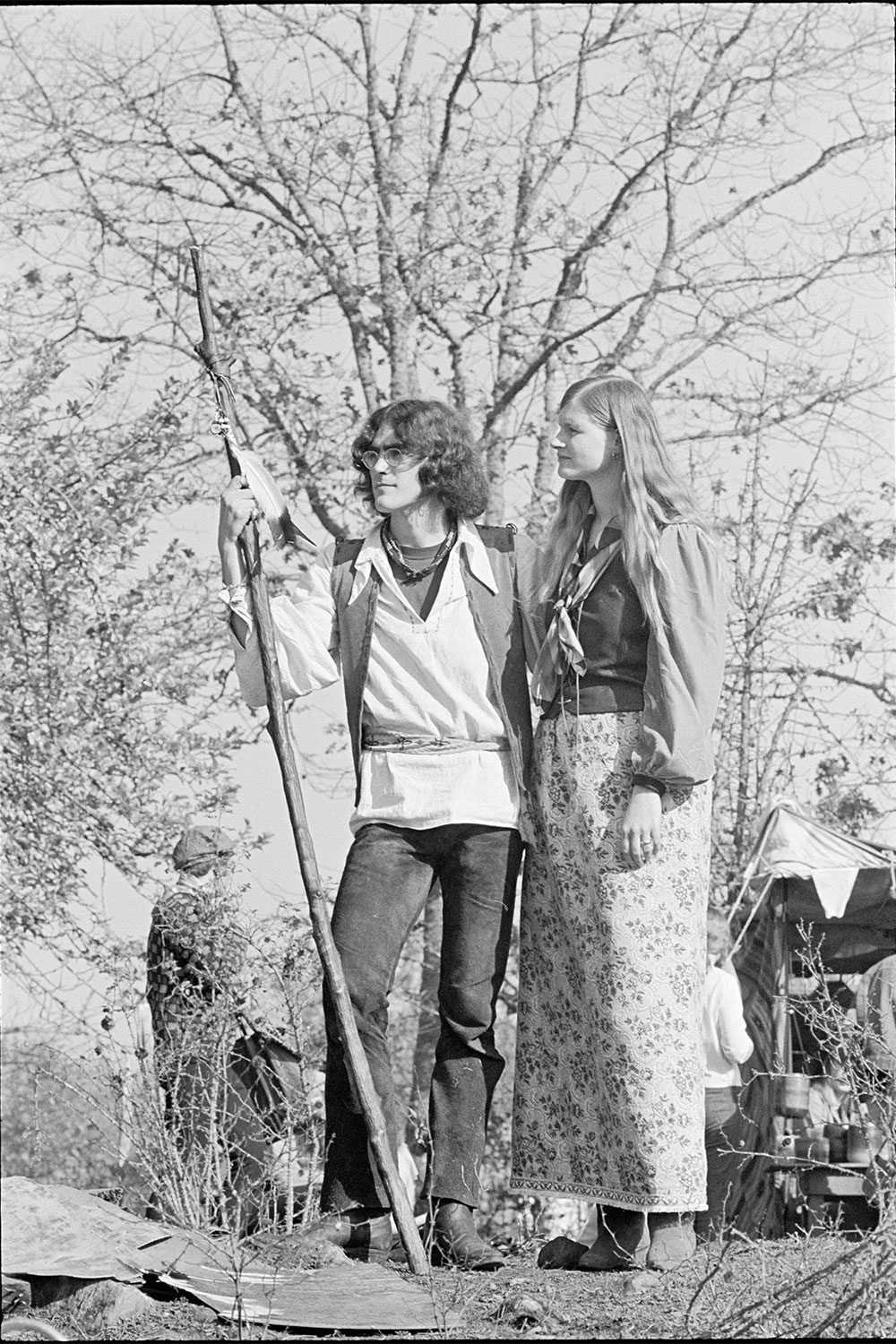

It all began on Nov. 1, 1969, at a rustic Renaissance Faire held in a teacher’s wooded pasture on Hawkins Lane in Eugene. Parents hammered together rudimentary booths out of recycled wood. Crafters set up tables and laid out blankets to display their candles, clothing, leatherwork and pottery. Minstrels sang while cooks served soups, barbecued chicken and homemade bread. The event made a modest amount of money for the school, but it sparked a feeling of community that would reverberate for decades.

Several dozen volunteers pulled together a second Fair in May 1970 on vacant property on Crow Road, with profits going to Family Counseling Services of Lane County. White Bird Sociomedical Aid Station, established only a few months earlier, set up a booth at the second Fair to offer counseling and first aid. Chuck and Sue Kesey sold their first-ever batch of frozen yogurt from the Springfield Creamery booth.

The Fair attracted many footloose young people who had grown disenchanted with mainstream society and sought to live more simply. In the 1970s, communes and collectives were popping up around the region like dandelions in springtime. Some folks went “back to the land” to farm. Crafters drove to the Fair in the house-buses and house-trucks that they lived in.

The third Fair, in October 1970, was the first to be held on the current site along the Long Tom River near Veneta and Elmira. Bill and Cynthia Wooten, proprietors of the Odyssey Coffeehouse in downtown Eugene in the late 1960s and early 1970s, rented the land for the event. The Odyssey was a popular gathering spot, and the Wootens would emerge as key Fair coordinators. For a decade, they would loosely lead a cadre of dedicated volunteers who brought the Fair to life with coordinator-led crews. The Fair coordinators made group decisions by consensus.

“We proceeded on the theory that community originates in communication and is established by cooperation,” the late Bill Wooten wrote about the early fairs. “We explored and demonstrated the possibility that a community can cooperatively manage its own experience without being dependent on handouts from bureaucrats and professionals.”

In 1975, in response to the threat of a lawsuit by the California Renaissance Faire group, coordinators changed the name of the Oregon event to the Oregon Country Fair, and they adopted a peach logo. The 1975 event had a transition name — the Oregon Country Renaissance Faire.

Also in 1975, Reverend Chumleigh (aka the Flaming Zucchini, aka Michael Mielnik) brought the first vaudeville stage show to the Fair and enlisted six students from Evergreen State College to play in a makeshift marching band. The “Chumleighland Stage” (officially dubbed the Circus Stage on the Fair map) would invite dozens of wildly talented entertainers — including the original Flying Karamazov Brothers — who would bring laughter and delight to Fair audiences for decades.

“Most of the booth people and others just loved having the marching band come through,” says Thaddeus Spae, who in 1975 composed “The Chumleighland March” for the band and played trombone, among other instruments. “We were doing this big celebratory ambient fest, you know, marching all the way around the Fair, whooping and whooping. This was really fun and really new.”

The marching band that paraded around the Fair’s figure-eight-shaped paths would grow over the years from six people to three dozen musicians. They called themselves the Fighting Instruments of Karma Marching Chamber Band/Orchestra. The band and the vaudeville acts added a higher, lighter vibration to the Fair’s mix of music and crafts.

In keeping with their ideals, organizers in 1977 opened the Appropriate Technology Area to showcase alternative energy and homesteading skills like beekeeping and organic farming.

In 1978, participants came to consensus to rename the area “Community Village.” Around the Appropriate Technology Area, they built a semicircle of booths to host groups promoting cooperative living and the causes of peace and justice.

By 1981, Appropriate Technology had outgrown its space in the village, and Fair coordinators opened Energy Park to demonstrate solar power and other alternative energy options. Community Village would continue to spotlight cooperative values, nonprofit enterprises and community networking.

Although Fair organizers gave away money to nonprofits after every Fair, they didn’t formally file for nonprofit status until 1977, when attorney Jill Heiman got the Fair recognized by the state of Oregon as a nonprofit. In 1980, Heiman helped the Fair jump through the hoops to become a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) federal nonprofit.

“When the Fair had to assume a legal identity, Jill was able to gently nudge that through doing a lot of that work herself,” says Ron Chase, who was Fair treasurer in the early 1980s. “She was the primary instrumental person in getting the 501(c)(3), which was crucial to the Fair’s future. Nobody else even recognized the importance of it, much less how hard it was to get.”

Growing Pains

With all the fun and hoopla, Fair organizers often failed to heed the impact the three-day event had on the neighboring communities. The constant traffic made it almost impossible for neighbors to run simple errands. People would trespass and tear down neighbors’ fences trying to sneak in to the Fair. Fairgoers with no place to stay overnight would sleep in neighbors’ pastures or park illegally on the roadsides, leaving behind trash. Neighbors also complained about nudity and drug use.

Lane County commissioners would get an earful of complaints. In 1971, the commissioners passed an outdoor assemblies ordinance that set in place requirements for gatherings of more than 1,500. At first, the ordinance focused on basics like the number of toilets per person. But each year the commissioners piled on more conditions, ratcheting up the demands.

In 1979, the commissioners added a $30,000 security bond on top of the requirement to purchase event insurance. At the county hearing, Heiman strongly objected to the bond, noting that it only applied to the Fair and unlawfully limited freedom of assembly. The commissioners waived the bond in 1979, but turned around and increased by 50 percent the Fair’s cost for extra sheriff patrols.

In 1980, the commissioners imposed a $10,000 bond requirement on the Fair, dismissing concerns expressed by the county attorney. Heiman quickly filed a lawsuit and sought an injunction on behalf of the Fair. The day before the injunction hearing and three days before the Fair was set to begin, county commissioners hastily gathered at the county attorney’s office and agreed to waive the bond for the 1980 Fair.

The lawsuit would wind its way through the courts for the next two years. The county eventually lost and agreed to settle. In February 1982, the county sent the Oregon Country Fair a check for $19,000. It couldn’t have come at a more auspicious time. Ironically, the county’s efforts to shut the Fair down would result instead in the Fair setting down roots for its future.

At the end of 1980, the property along the Long Tom River had been put on the market. By then the land was down to 240 of the original 400 acres that the Fair first leased in October 1970. The remaining low-lying woods and wetland prairies were subject to seasonal flooding from the Long Tom River that meandered through the site. The owners priced the acreage at $325,000, and asked for a down payment of $100,000, a high hurdle. Only $24,000 sat in the Fair’s bank account after the 1981 event. Organizers had raised another $25,500 with a charter membership fund drive, plus T-shirt and bake sales.

With the county settlement in hand, Fair treasurer Chase and attorney Heiman negotiated terms to pay half the down payment before the 1982 Fair and half afterward. On July 8, 1982, the day before the Fair began, Chase made the first $50,000 down payment.

Six weeks after the euphoric 1982 Fair, organizers rented the Fair’s parking lot fields to the Springfield Creamery for a Grateful Dead concert — the Second Decadenal Field Trip. The rental fee helped meet the second down payment in December 1982.

A few months after signing the purchase agreement, Fair organizers learned that the state highway department planned to reroute Highway 126 through the Fair’s parking lot, chopping off the south edge of the property. Numerous hearings resulted in several archaeological digs, where it was proven that the Fair property indeed contained archaeological sites just as significant as the ones the highway department had been trying to avoid.

Artifacts in a 1986 study in the highway right-of-way indicated that the Kalapuya peoples had settled in the valley for thousands of years. The oldest site dated to 11,000 years ago; the first rock ovens dated to 8,000 years ago.

The highway compromise resulted in Highway 126 being rerouted along the Fair’s southernmost border, cutting off only a small corner of the property. The Fair got a new south-side entrance in the deal, which considerably reduced the traffic jams that had caused the neighbors so much grief.

A Multi-Generational Fair

Despite the hassles, coordinators maintained their sense of festivity. At a meeting in the 1980s, coordinators defined the purpose of the Fair as “psychospiritual rejuvenation.” Each Fair still served up a three-day smorgasbord of magical whimsy and musical fun for thousands of Fairgoers. More and more people came to the Country Fair each year to sample the entertainment at a dozen stages, enjoy a cornucopia of cuisines, and shop the exquisite, handmade crafts in the booths lining the Fair’s pathways.

The Fair “is not just an alternative to the dominant culture,” notes Leslie Scott, who was hired as general manager in 1992. “It’s an absolute reflection of the dominant culture, but it shows how you can live happily and successfully and beautifully very differently inside the dominant culture and have an influence. It shows you how you change culture and how you create culture.”

In 1993 Scott worked with the city of Veneta and Fair volunteers to open Zumwalt Park at the Fern Ridge Reservoir to public camping during the Fair. The park offered Fairgoers a welcome place to stay, but wasn’t big enough to handle the demand. In 1996, Fair organizers helped gain county approval for neighbors in Veneta and Elmira to set up temporary campgrounds in their pastures and fields during each Fair. The neighborhood campgrounds quickly became integral to the Fair experience for hundreds of Fairgoers. By 2018, the campgrounds generated so much traffic that Lane County this year stepped in to work out solutions.

Through the years, the Fair purchased several adjacent properties to the original land. To provide relief from the crowds jamming the original figure-eight-shaped pathway, Fair organizers extended the footprint of the event. In 1991, a new loop called the Left Bank was opened near the entrance. In 1997 the Left Bank was extended to include more booths, stages and a large kid-friendly area called Chela Mela Meadow, named for the band of Kalapuya Indians who gathered annually on the property thousands of years ago. The Chela Mela Meadow features plenty of open space for yoga classes, hands-on art for kids and juggling lessons. The footprint grew again in 2015 with a new area later dubbed Xavanadu, which includes a dance pavilion and a big meadow with more room to play.

The Fair expanded entertainment over the years from four stages in the 1970s to 20 today. Instead of one stage showcasing vaudeville acts, now at least four stages book acts all day long — silk aerialists, clowns, mimes, a bubble artist, jugglers, puppeteers, acrobats, juggling acrobats and other amazing performers.

The twice-daily marching band parade started a trend. Now Peachi the Dragon makes her way through the throngs each day, and many mini-parades pop up along the pathways.

In 2001 the Spoken Word program launched, inviting dozens of speakers annually, such as Amy Goodman, Eugene Poetry Slam, Stephen Gaskin, Rob Brezny, Ram Das, Patch Adams and Pete Seeger.

Through the decades, Fair musicians have come from all over the sonic map. Early Fair favorites included local bands Wheatfield, Mithrandir, and the Crazy 8s. Regional musicians Jim Page, Baby Gramps, Laura Kemp, Artis the Spoonman, Alice DiMicele, Scott Cossu and Brian Cutean regularly perform. World beat bands gracing the stages ranged from Shumba, Caliente, and Zulu Spear in the 1980s to Los Mex Pistols del Norte, Samba Ja and Afrolicious in the 2000s.

For years, rumors swirled that the Grateful Dead would play at the Fair. That never happened, unless you count Grateful Dead playing in the Fair’s parking lots for the “Field Trips” concerts in August 1972 and August 1982. Separately however, Grateful Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann and lyricist Robert Hunter performed on Main Stage with other talented musicians in the 2000s.

In 2019, the Fair that was founded by young people finds itself at a new juncture. Two and three generations of families share booths and put on shows. The Elders group offers a place for people to step aside from their Fair jobs, making room for younger generations to step up. In September 2018, the Fair received a $12,000 grant from the Oregon Cultural Trust to create an archive. This summer, exhibits at the Lane County History Museum and at the Central Library in Portland will celebrate Oregon Country Fair’s 50-year history.

“It’s hard to imagine it’s still going now, because it came from a time that America seems to have forgotten in many ways,” says Wren Arrington, events coordinator for White Bird. “My kids grew up here. I started coming before I had children, and now my son is 35. He’s been on Fair crews, he’s been a crew coordinator. Just last year he got his own food booth and I got a grandson. … We joke about how someday they’re going to be wheeling us around in chairs and parking us by the Main Stage while they go do the all the work. I think there’s an element of truth to that. I think the Fair will keep on going and keep on evolving. It may not always look the way it does now. But it’s not just an event, it’s a community. That’s the part that’ll stay constant.”

Looking Ahead

While honoring the past, Country Fair organizers keep their eyes to the future. The next generation is moving into leadership. Fair General Manager Crystalyn Autuchovich, now 35, grew up as a “Fair kid” in Community Village, where her father, Arthur Jones, has participated for decades. The Fair board is in the midst of hiring a new executive director to help manage the year-round organizational efforts.

But of immediate concern, the damage to the Fair’s forests from February’s snowstorm poses challenges to getting everything in shape by July. Numerous mature trees in the Fair’s forestlands toppled over, severely damaging booths around the site. Even so, volunteers are planning a stupendous celebration for the Fair’s 50th, with everyone pitching in once again to create “the best Fair ever.”