On a warm, sunny Sunday afternoon in May, hundreds of people crammed into the gymnasium at Burns High School in eastern Oregon for a concert. One estimate put the crowd at 700. That’s roughly a quarter of the population of this remote high-desert town.

In Oregon’s cowboy country, people hadn’t come out for a honky-tonk band or a rock ‘n’ roll star on tour. Instead, the crowd of townspeople and out-of-town visitors, white-collar workers, grocery clerks, binocular-wielding birders, government scientists and ranchers had shown up for the world premiere of a brand-new classical symphony.

“The place was filled,” says local writer Terry Keim, who was at the concert. “It really hit a chord in the community.”

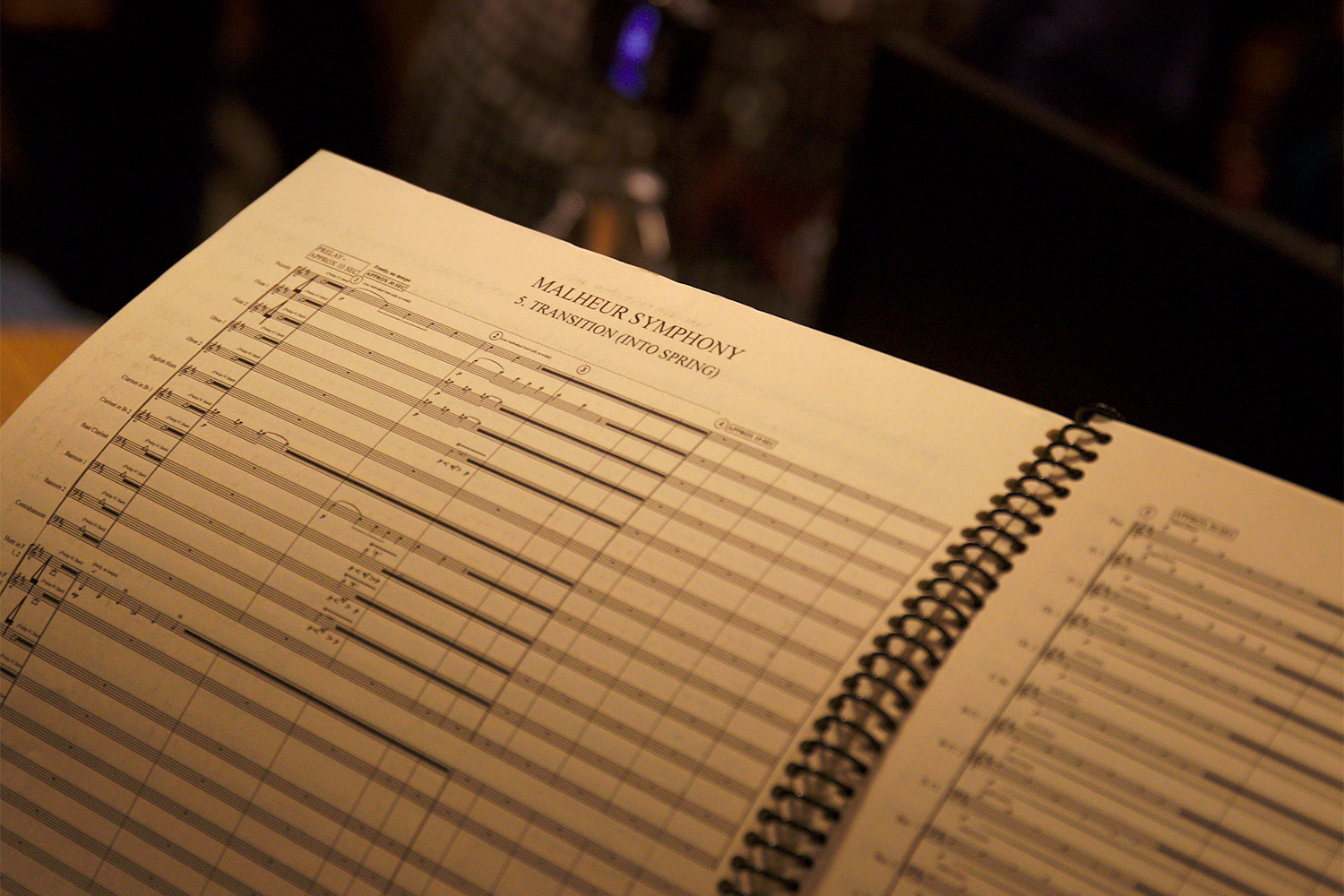

The five-movement Malheur Symphony, as the work is titled, was composed by Christopher Thomas, a Bend musician accustomed to having his music performed at much larger venues. His suite Music For Strings is to be performed in August at Australia’s Sydney Opera House.

A frequent composer for film, Thomas has worked with such Hollywood names as Samuel L. Jackson, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Zoe Bell.

Malheur Symphony, which was played that afternoon in Burns by the Central Oregon Symphony from Bend, refers to Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, which in early 2016 was the scene of a 41-day takeover by armed right-wing extremists. The occupation of the refuge, 30 miles south of Burns, stunned and, for a time, divided the community. Harney County is the kind of face-to-face place where politics quickly becomes personal.

A year after the occupation ended in gunfire, arrests and the death of one of the occupiers, Thomas was approached by Jay Bowerman, one of three sons of Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman and a lifelong naturalist and supporter of environmental causes.

Could Thomas, Bowerman wondered, compose a piece of music to honor Malheur Refuge in the wake of the occupation? Could he produce something that might help the fractured community reunite in the wake of the ugliness and violence?

“The real philosophical reason for doing this was to use music as a form of healing,” Bowerman explains. “You know, what I don’t want to do is dredge up those old hard feelings on either side, right? And so I guess, simply put, it’s just the idea that music can be a powerful force for healing. And there’s a real need for healing in that community over there — and far beyond that community, in the country and the world.”

Thomas signed on. The two men spent several days together exploring the refuge and its surroundings. They met native Paiute leaders from the Burns Paiute Reservation, situated on the edge of town, and talked to ranchers, scientists and other members of the larger Harney County community.

Out on the refuge, Thomas recorded the sounds of the wind, of thunder and of birds singing in the marshes.

Bowerman had imagined a single short piece of music. But as they headed back to Bend on the 130-mile desert highway connecting the two towns, the composer fell silent for long stretches. Everything from ancient geology to the traditions of the native Paiutes to birdcalls and ranchers in cowboy hats was swarming through his mind.

Enlarge

“And suddenly this beautiful architecture showed up,” Thomas says. “And I said, ‘Oh shit, we’ve got a symphony on our hands! It’s five movements.’” He had never before composed a symphony. “But, you know, if Brahms and Berlioz can do it, we can do it!”

As everyone knows who lives outside the Fox News bubble, we live today in a time of crisis, both political and environmental. American democracy seems a thing of the past, pushed aside by greed, corruption and gerrymandering at the political high end, and by extremists with assault rifles at the bottom.

Meanwhile, as scientists are reminding us in increasingly urgent reports, our planet is quickly running out of time — no matter what breed of politicians happens to be in charge.

As a result, an informal connection between artists and scientists is creating what amounts to a new genre of music. You might call it “music to heal a dying Earth.”

In Nomine Terra Calens

In Los Angeles, scientist Lucy Jones was known for years on television as “Dr. Lucy.”

Now retired, she spent three decades as a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and as a research associate at Cal Tech. Unlike many scientists, Jones made a point of being accessible to the news media when reporters had questions about, say, this afternoon’s temblor.

Once — to the delight of Southern California TV viewers — she cradled her sleepy young son as she appeared live on camera to discuss a massive earthquake that had just struck in Joshua Tree. The L.A. Times called her “the Beyoncé of earthquakes.”

Jones, whom I’ve known since we were in grade school together in L.A., has also been a musician all her life, taking up the viol — a Renaissance stringed instrument with frets — when she was an undergraduate at Brown University. Returning to music as her children grew up and as she wound down her job with the Geological Survey, she now plays viol with Los Angeles Baroque.

A few years ago on YouTube she heard a piece of music that simply transcribed rising global temperatures into notes. “It wasn’t music, but it was, you know, interesting,” she says. The idea inspired her to use similar data to compose something with more musical heft.

It took her several years to complete. “The last time I actually composed a piece was in college,” Jones says. “I did take a theory class in college.”

Enlarge

The result is In Nomine Terra Calens — “In the Name of a Warming Earth” — which is based on average global temperatures since the 1880s. It’s written in a 16th-century English musical form — called “in nomine” — for several stringed instruments, usually viols; in it, one instrument plays a foundation theme, around which the others play polyphony.

Jones uses historical climate data for that foundation theme, resulting in a pitch that rises faster and faster throughout the seven-minute composition. By the end, she says, the notes are so high they’re difficult to play.

“This data is like a graceful minuet accelerating into a frantic jig,” she notes on her website.

In February Jones and other members of L.A. Baroque performed In Nomine Terra Calens at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. She also worked with an animator to create a visual depiction of the climate data to go with her music on YouTube, where it’s received 30,000 views since it was posted May 15.

This, Jones says, is art sending a message that’s loud and clear.

“I don’t understand why people aren’t more terrified by what’s going on,” she says. “We should be talking about restoring our world, and we’re just like putting our heads in the sand.”

An Apocalyptic Genre

Malheur Symphony and In Nomine Terra Calens mark just two data points in a growing wave of new music being created in recent years, says Robert Kyr, a professor of composition and theory at the University of Oregon School of Music and Dance.

“More and more composers are feeling called,” Kyr says, adding that he uses the term “called,” with its religious overtones, decidedly. “We need to awaken to new possibilities of understanding our relationship with the natural world and our obligation to serve as the very best stewards of our incredible environments and our incredible planet.”

Perhaps the most noted composer in this vein has been John Luther Adams, who for years has incorporated natural sounds into his environmentally oriented compositions. His orchestral work Become Ocean, which won the Pulitzer Prize in music in 2014, draws its title from a poem by composer John Cage.

“Life on this Earth first emerged from the sea,” Adams explains in a program note. “As the polar ice melts and sea level rises, we humans find ourselves facing the prospect that once again we may quite literally become ocean.”

Kyr — who was a professor of Thomas’ when the younger composer studied at the UO — has created his own works with a climate theme.

His 2007 A Time for Life: An environmental oratorio was commissioned and recorded by Portland vocal ensemble Cappella Romana. Divided into three parts — “Creation,” “Forgetting” and “Remembering” — the work weaves in sources from a Native American prayer to a 1961 “Service for the Environment” written by an Eastern Orthodox monk at Mount Athos monastery in Greece.

“Music can reach people at levels that perhaps nothing else can,” Kyr says. “And so as composers, we have a particular obligation to use our musical gifts to address these issues and to impel people to take action.”

Birdcalls from a Desert Marsh

By all accounts, Malheur Symphony was an unqualified success at its May 5 premiere in Burns.

“It was a nice way to reclaim that space,” Keim said of hearing Thomas’ music in the high school gym, which had been the scene of a contentious community meeting during the takeover.

“The goal was accomplished,” agreed Burns music teacher Marianne Andrews, who was also there. “They didn’t dwell. The people of Harney County are done discussing it. But they were thrilled with the beauty of the symphony.”

Though I missed that premiere performance in Burns, I was able to hear Malheur Symphony at one of three performances later given by the Central Oregon Symphony in Bend.

I’ve been going to Malheur Refuge for three decades, often visiting three or four times a year with my son, Noah Strycker. We both feel a deep connection to the place and the community around it, and he joined me at the concert.

I was, I will say, apprehensive as the music began. Contemporary classical music has a well-deserved reputation for being inaccessible to mere musical mortals.

But from its quiet opening, Thomas’ symphony was not only warm and listenable but also smart and complex. The entire audience — which nearly filled Bend High School auditorium on a Monday night — was rapt for the full half-hour the symphony takes to perform.

As the music died down, before the applause erupted, my son looked over at me. A birder, he’d been listening not only to the music, but also to the birdcalls Thomas had woven into it, including a marsh bird called a sora.

“I’ve never heard a symphony with a sora,” Noah said. “It felt like being at Page Springs Campground on a morning in June. He got it.”