It’s nearly 10 am on a drizzly spring Saturday in Eugene. For the past two hours, a mountain of a man armed with a backpack-style leaf blower has worked his way around Sheldon High School’s softball field, ushering the large puddles of water toward a drain on the sidewalk. The rain steadily recollects on the infield.

Soaked through his Bill Belichick-style sleeveless hoodie, the former University of Oregon defensive lineman is preparing the diamond, determined to get the work done so that his 17-year-old daughter, Olivia, can play in one of her final high school softball games.

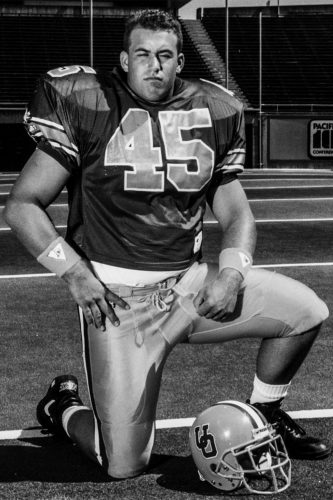

It is this kind of determination that earned Mark Schmidt, now 43, a chance to play on the Ducks’ legendary mid-’90s defense dubbed “Gang Green” by the longtime defensive coordinator Nick Aliotti. But it was a speech on the practice field that made him who he is today.

Schmidt’s career in sales and marketing for Keystone Hardscapes keeps him busy, managing sales from Tacoma, Washington, to Redding, California. Yet he has become a beacon of authority and hope to the high school football and softball players whom he coaches as a former division one athlete and college graduate.

While many coaches simply teach the x’s and o’s, he has made it his mission to teach young people to be passionate about their respective sports, to work hard every day on and off the field, and to enjoy life.

Schmidt wasn’t the most famous member of that 1994 Duck defense — the one people remember for playing in the Rose Bowl and being on the field for Kenny Wheaton’s clutch interception that sealed the iconic win against Washington. And, when Gang Green gets honored this fall at Autzen for their 25th anniversary season, he’ll likely not get the loudest cheers. But that’s OK. Around Eugene, the kids he works with weren’t even born in 1994. They remember him for what he’d done lately.

Schmidt had a strong work ethic from the time he was in high school. As an all-state star baseball and football player for Clayton Valley High School in Concord, California, Schmidt worked hard on the field to make it to college. He said, “I was being recruited by pretty much every school.” In the end, Schmidt chose to play football at the UO.

When he got to Eugene in fall 1993 he developed a “hot-shot” mentality, and it nearly derailed his college opportunity. As a player further down the depth chart, coupled with the ’93 Ducks’ low expectations, Schmidt became unfocused. “I almost flunked out of school my first year here. I was a dog off a leash. I would just drink, party and not go to school,” he says.

But that would change in his redshirt freshman season — and one moment made all the difference.

After being beat down at Hawaii in the second game of the season, the 1994 Oregon football team was back in Eugene at the practice field. Tempers ran as hot as the sweltering September air. A fight broke out between senior linemen Gary Williams and Matt Martin. Then a player had a knee injury. Next a player got a concussion. And still the scrimmage went on. The field was littered with injured and exhausted players when the practice ended.

As the team gathered together before leaving the field, wide receiver Kory Murphy, who had suffered a career-ending neck injury during the Hawaii game, stood in front of 110 men and spilled all of his frustration and emotion onto his team. He said they would never know when their last play might be so they’d better not waste it. His impromptu talk moved many players, including Schmidt, to tears.

Schmidt says, “Kory’s speech touched me to my soul.”

Murphy’s words were so profound that Schmidt kept them with him throughout the season and his life. “It just changed the mindset of a lot of young athletes that, probably were a lot like me — just going through the motions,” Schmidt says.

The speech inspired the players to buckle down and play for each other. They made it to the Rose Bowl for the first time since 1958. For Schmidt, the speech prompted him to work harder off the field as well. He would become the first in his family to graduate from college, earning two degrees: one in sociology and one in business management. But, as Schmidt transitioned from college to post graduation, he found a new motivation.

Eugene native Kara Jones worked at a barbershop on the UO campus while attending Lane Community College. In December 1996, she started dating Schmidt. “Everyone says that he was wild before I came along. I’ve never seen the wild side,” she says. “He’s always been kind, loving, generous, supportive and very outgoing.” The Schmidts celebrated their 20th wedding anniversary in May.

“What keeps me motivated is the four girls in [my] house: my three daughters and my wife,” Schmidt said.

In the past 20 years, the Schmidts have raised their daughters. Yet, through tutoring and mentoring the players that Mark has coached, they have impacted countless more teenagers’ lives.

Schmidt has held head and assistant coaching positions at Thurston, Willamette and Sheldon high schools. He has a saying that he tells his daughters and his players: “You want to be known for the dash.” He’s referring to the time between when a person is born and when they pass on. ‘The dash’ is a reminder to live life well and make an impact during one’s lifetime.

“Our whole purpose is to lift others up through edification,” Schmidt says in regards to his unique coaching style that focuses on more than just the game. He has gone as far as buying school supplies and tutoring the players he coaches, teaching them the value of education while helping improve their grades.

One player whom Schmidt helped on and off the field is Chantz Hecht. Like Schmidt, Hecht played defensive lineman for Thurston High School. Nearing the end of his time at Thurston, Hecht was behind in many of his classes and had a 2.0 GPA. Fearing that he would not be able to graduate, Schmidt took Hecht under his wing.

Schmidt offered to have Hecht come to his house so that he could tutor him. “I would stay there a few nights a week and we would make sure my homework was done,” says Hecht, who graduated from Thurston in 2014. “I didn’t really have that push like he gave me. Same with his wife and his family: They really all were in on it to help and motivate me. That’s the kind of person he is, he just wants to help others.”

These are the moments that define Schmidt’s “dash.”

Although Schmidt is honored to have mentored hundreds of athletes in his 20 years as a football coach, his favorite players to teach are his daughters.

Olivia Schmidt, his oldest daughter, says, “He teaches more about the sports and the aspects of life than I think anybody else could ever do,” as she reminisces on dad-daughter softball practice sessions in the front yard that turned into neighborhood-wide pick-up games.

All of Schmidt’s time and dedication to his daughters paid off. Olivia was a catcher on the Sheldon softball team that won the 2019 state championship this spring. Following in her father’s footsteps, she received a scholarship to Saint Martin’s University to play her favorite sport and continue her education.

On the day many Oregon football alumni attended the 2019 Spring Game, Schmidt did finish preparing the Sheldon softball diamond just in time for his daughter’s game. He proudly watched as Olivia smacked the ball out of the park for a home run.