Four years ago, my wife and I, with occasional help from our grown son and a couple friends, planted 700 trees at our place outside Creswell.

With buckets, shovels and endless optimism, we stuck one small bare-root Douglas-fir seedling into the ground after another, chopping out weeds and grass, working Sunday after Sunday, rain or shine, until we had begun the process of turning two blackberry-infested pastures back into forest.

We started the project because, over the past 10 years, most of the trees around our property have disappeared. If you were to draw a circle with a five-mile radius around our house, I’d bet that half the trees inside it have been cut in the past decade as the neighborhood has begun to suburbanize.

People buy houses in the country and, first thing, they cut all their trees — for light, for open space, for help with the mortgage payments. Hundreds of acres of trees disappeared in one felling swoop near our house when a developer bought land from an old farming couple and cashed it out.

With each land sale and each load of logs, our world became noisier and less private.

In the beginning we planted trees because we wanted our old world back. Only gradually, as we set tree after tree into the muddy winter ground, did we begin to think about the greater issues of climate change and reforestation. We weren’t just ensuring privacy. We were helping to save the Earth, one tree at a time.

Then the Douglas-firs began to die.

Our place consists of 18.66 acres of land — about half forest and half pasture. It’s the remnants of a 40-acre homestead filed by a Civil War veteran from Iowa named Daniel Spencer, no relation to Spencer Butte, who went on in the 1920s to write a column about his war experiences for the now-shuttered Springfield News.

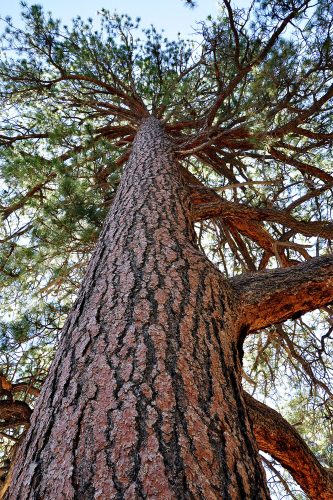

When we bought the land, it came with a deteriorating 19th-century house, possibly built by Spencer himself, as well as a medley of strange antique farm equipment, stands of enormous Douglas-firs and spectacular end-of-the-cul-de-sac privacy.

It was the middle of the 1980s recession. The couple who had lived on the property for 17 years couldn’t get a local real estate broker to list it, given that the house wouldn’t qualify for conventional loans due to its lack of foundation, insulation or code-worthy plumbing. We heard about it only when we saw a pennysaver newspaper ad placed by a farm agency in Chicago.

We called the agent, who gave us directions. We drove out and, not finding the owners, walked around and looked. The house was small but interesting, in a weathered clapboard-y way. It was spring. Apple and pear trees were blossoming in an orchard in the back yard. The land was gorgeous.

The next thing we knew, we were the owners of a lot of trees, about which we knew almost nothing, and a slightly dilapidated house that caused a friend to gush, “It’s like summer camp!”

We put in a large fenced garden and learned to grow vegetables. We began remodeling the house to the point a loan officer might not look at it and sneer, a 20-year project. I learned the mysteries of owning and operating the tools of rural Oregon life: chain saws, weed eaters, a commercial grade tiller with a field mower attachment, a riding mower.

Lesson No. 1 for the aspiring rural homesteader: Don’t scrimp by buying cheap tools. The essence of life in the country is a non-stop battle with grass, brush and trees that grow where you don’t want them. You need the best gear possible.

An unexpected visitor one Sunday afternoon that first spring was an elderly woman whose son drove her out to the house — our house now — where she had been a girl in the 1920s. We were charmed by her stories of life in a day when Bear Creek Road was paved with planks. In winter she and her siblings walked a couple miles through the forest to get to school, the muddy plank road being too challenging.

As she and her son were heading back to their car at the end of our visit, I asked her what looked the same and what looked different. She pointed to the stand of big Douglas-firs that line our driveway.

“Those trees weren’t there,” she says. “That whole slope was cut over.”

Douglas-fir became the official state tree of Oregon by act of the Legislature in 1939, recognizing the tree’s outsized economic importance.

How could there ever be any question in our minds what kind of tree we would plant?

Once we had decided to reforest the two pastures, the first step was to remove what seemed like a million tons of blackberry vines that were in the way. Our walk-behind field mower had its limits. For a month I was calling and emailing people who advertised tractor services. Most never called back. A couple made appointments and never showed up. Finally, I reached out to our 80-something neighbor Vern, a former ranch manager who owns a big John Deere with a mower deck.

The next morning Vern, dressed in tan coveralls and wearing a facemask, plunged into the thicket, deftly reducing impossible tangles of thorny vines into fibrous clippings. In the process he turned up the relics of 140 years of human occupation: Foundation stones for a long-gone barn. Drainage pipes. Strands of barbed wire, of course, and even rolls of the stuff, as well as steel T-bar fence posts that had long ago toppled and sunk into the topsoil.

We found the axle from an ancient car, with rotten whitewall tires still attached, and various smaller car parts scattered nearby along a low ridge. We removed what we could carry and left the axle and tires behind.

The worst blackberries were too much even for Vern’s Deere. I finally found a contractor who operated a machine so ruthlessly destructive it could have come from a Mad Max film: a rotating steel drum the size of a small car ground up everything in its path. Eight-foot-tall stands of blackberries, tangles of Scotch broom, poison oak and even small trees disappeared into its whining maw, leaving a uniform layer of mulch as soft as fine planting soil.

At last we were ready for trees.

We bought them from Brooks Tree Farm in Salem, a nursery recommended by a friend. They were unfailingly pleasant and prompt to deal with.

Kathy LeCompte and her husband, David, who both come from forestry backgrounds, founded the business in 1980. Starting with a couple groves of Douglas-fir that first year, they grew the business to where they manage about 5 million trees today.

Throughout that winter I’d call Kathy on a Monday, and on Thursday two brown bags of 50 trees each would appear at our house, delivered by UPS, ready for the weekend’s work. We mostly bought Douglas-fir, though we mixed in the occasional bag of western red cedar or western hemlock. We planted them one by one, then put plastic deer cages around them, held up by bamboo poles.

In the meantime we noticed a poster advertising a Creswell High School fundraiser. The kids were selling tree starts. I bought a bag, which contained a mixed lot of the usual suspects, but also had three Ponderosa pines — those beautiful tall salmon-pink trees you see in eastern Oregon. A desert tree.

Desert trees can’t possibly grow here, I thought. We planted them anyway.

The first signs of trouble came that July. It’s almost always dry in the Oregon summer, but this one was scorching, with clear skies for weeks on end and afternoons in the high 90s. I’d walk around the two pastures and look at the little trees in their plastic cages. Nearly all of them were alive, but none looked happy. Our new trees were droopy, and their needles were beginning to brown.

Water seemed to be the issue, and I bought a few hundred feet of garden hose to add to the few hundred feet we already had, and began hand watering. I dragged hoses far into the pastures each week, spraying hopelessly, wetting down one tree at time.

By August it was clear we were in deep trouble. Most of our trees — almost all of them, actually — looked dead. We’ve seen plenty of plants come back from the brink, so we weren’t going to pull anything out until the following spring. But we knew they were gone, and they were.

All except those three Ponderosa pines. They were flourishing.

The following winter I was back on the phone with Kathy each week, ordering Ponderosa pines to replace the hundreds of trees we had lost that first year. By that time we were good enough at planting that the prospect of putting in another hundred starts just seemed a regular part of Sunday.

Three years later, nearly every single pine tree we planted that winter is thriving.

It turns out a subspecies of Ponderosa pine, one that is related to but not the same as those big trees in the high desert, once grew across much of the Willamette Valley. The tree was common in mixed forests around Eugene, recent research shows, and only began to die off as European settlement put an end to the fires, set by Native tribes, that had kept competing species such as Douglas-fir from shading them out.

In 1994 a group — now called the Willamette Valley Ponderosa Pine Conservation Association — came together to identify what seed trees remained in the valley and to save what was left of the subspecies.

Enter Kathy and Dave LeCompte.

“We began buying the seed right away,” Kathy explains over the phone. “It turns out it really grows quite well here. They nearly all had vanished, and a lot of people are surprised they grow here at all. I am surprised, myself.”

Brooks Tree Farm is now at full capacity for growing the pines. “We sell all that we can grow,” she says.

So what happened to our trees?

I’ve talked to a number of people over the years about our experience, asking both as a landowner and as a journalist. A series of background discussions I had with local timber industry representatives a couple years ago was enlightening. No one denies that Doug-fir plantations are sometimes failing, but no one will say out loud that this has anything at all to do with human-caused climate change.

On the record, I checked this month with tree professionals from various backgrounds. It turns out, of course, that the answer to my question is complicated.

Without knowing exactly what trees we planted and how we did it, the more-scientific people I talked to were reluctant to draw firm conclusions about whether climate killed our Doug-firs. They could have died from poor handling, from bad soil, from soil compaction or a variety of other stresses.

But David Shaw, a forest health specialist with the Oregon State University College of Forestry, acknowledges that Douglas-fir has been in trouble in recent years.

“I think your timing was just unlucky,” he says in an email. “2015, 2016, 2017 [and] 2018 were unusual, and anecdotal reports indicated lots of failures in recently planted trees, and in some Christmas tree seedling plantings, too. There has been lots of Douglas-fir mortality in the oak zone. We are generally attributing these mortality events as drought- and heat-related.”

Activists are less circumspect. Friends of Trees is an organization based in Eugene and Portland that promotes tree planting.

Logan Lauvray, the organization’s green space program manager, says yes, trees are dying from the climate, and not just Doug-fir. “The general consensus I am hearing amongst ecologists is pointing to climate change,” he says in an email.

“I have not seen any hard studies on this,” Lauvray says. “Certainly anecdotally, we are seeing Douglas-firs dying at a higher percentage — even ones that are 10 to 30-years-old and well established. Same with western red cedar, and I did recently see something pointing to bigleaf maple may be at risk as well.”

Christer LaBrecque, restoration projects manager for McKenzie River Trust, manages the trust’s 1,000-acre Green Island west of Coburg.

In 2006 the trust began planting what now amounts to some 800,000 trees and shrubs on the property. The trees were a mixture of species, including Douglas-fir and Ponderosa pine. “We don’t plant a ton of Douglas-fir,” he says. “Maybe 5 to 10 percent of what we’re planting.”

Looking around the island today, he says, what you see is groves of Ponderosa pine. “It looks unnatural,” he says. “We planted everything — and mostly the pine survived.”

Erik Burke, Eugene director of Friends of Trees, takes a long view of the situation. The climate in western Oregon has oscillated between cool and warm cycles for 2.5 million years, he says.

“The general climate pattern has been 100,000 years of cool — glaciation or ice age — followed by 10,000 years of warm (interglacial) period, with lots of smaller cycles within that,” he says in an email.

Douglas-fir, he says, took over western Oregon during one of those cooling cycles. But that cool period has been interrupted in the past 50 years by human-caused warming.

“Severe droughts like our last five-plus years before this September are tough on Doug-fir, and it’s no surprise they are getting many diseases and widely dying throughout our region, and becoming harder to establish,” he says. “I expect many or most of the Doug-fir forests around Eugene area to die from fire and disease in the next 30 years if climate change continues.”

That’s a bleak picture. Earlier this month we ordered another 50 Ponderosa pine starts from Brooks Tree Farm. We planted half of them in gaps in our budding pasture-forest — and the other half in sunny spots among the existing tall Doug-firs in our established forest.

If Burke is right, those elegant tall trees that line our driveway may be doomed, but at least we’re inviting a new generation of tall, beautiful trees to grow up and take their place. ν