In 1886, 27 years after Oregon became a state, the citizens of Lane County decided to help the poor. They gathered together and wrote a letter to county officials, petitioning for a county poor farm.

They wrote the letter at a time when self-reliant Oregon Trail pioneers were still alive, when the federal government didn’t intercede to help the jobless and homeless, when cities and counties had to take care of their own.

Because of this, poor farms became a fairly common practice around the country for citizens who needed food, a job and a place to sleep. The farms were run by towns or town residents and supported financially by local governments.

Today, service providers and experts in Lane County believe the community’s present homelessness crisis is a recent problem because the culture of a transient lifestyle has evolved over the last hundred years.

The number of people experiencing homelessness in the Lane County annual Point-In-Time count has spiked. When the count first started in 2013, there was an estimated 1,751 people experiencing homelessness. In 2019, it’s 2,165.

Even if extreme chronic homelessness is a recent phenomenon, the ways in which people have come together to help the homeless isn’t.

Looking at the history of homelessness locally, people who wanted to help the less fortunate in the community came together to create a space for the homeless to live. As the 20th century rolled along, the federal government stepped in to help the poor, and the Eugene City Council pushed the problem aside.

The question of how to help and who should help the homeless wasn’t a frequent topic at city meetings. In the early to mid 20th century, due to economic and cultural shifts, more people were forced onto the streets, leading to the high numbers of homelessness seen today.

Although not every solution has proven successful, the history remains: We used to help the homeless.

Enlarge

Image courtesy Lane County History Museum

The Poor Farm

Local historian and author Steve McQuiddy says that since white people came to Eugene in 1846, the population has been transient. European immigrants and American migrants dissatisfied with their lives risked the hazards of the Oregon Trail and settled in the Willamette Valley.

“If you look at Eugene, you’ll see in general Eugene’s character is formed with dissatisfaction for the way things were. So they are out there looking for a new place to be,” McQuiddy says.

He adds that even the natives, the Kalapuya people, moved around with the seasons.

“It’s an attempt to find a balance between satisfaction with the way things are in an attempt to improve things so we can accommodate others who are not like us,” he says.

At the time, poorhouses were often synonymous with workhouses, echoing a Dickensian London where poorhouses existed to exploit and mistreat the impoverished. Because of this dark background, The Oregonian newspaper proposed an alternative name: “poor farm.”

Several other counties in Oregon at the time had poor farms, and perhaps the best known is the Multnomah County Poor Farm in Troutdale, which operated from 1911 until the 1950s, when it was converted to a lodge. Today, it serves as a McMenamins restaurant and hotel called Edgefield.

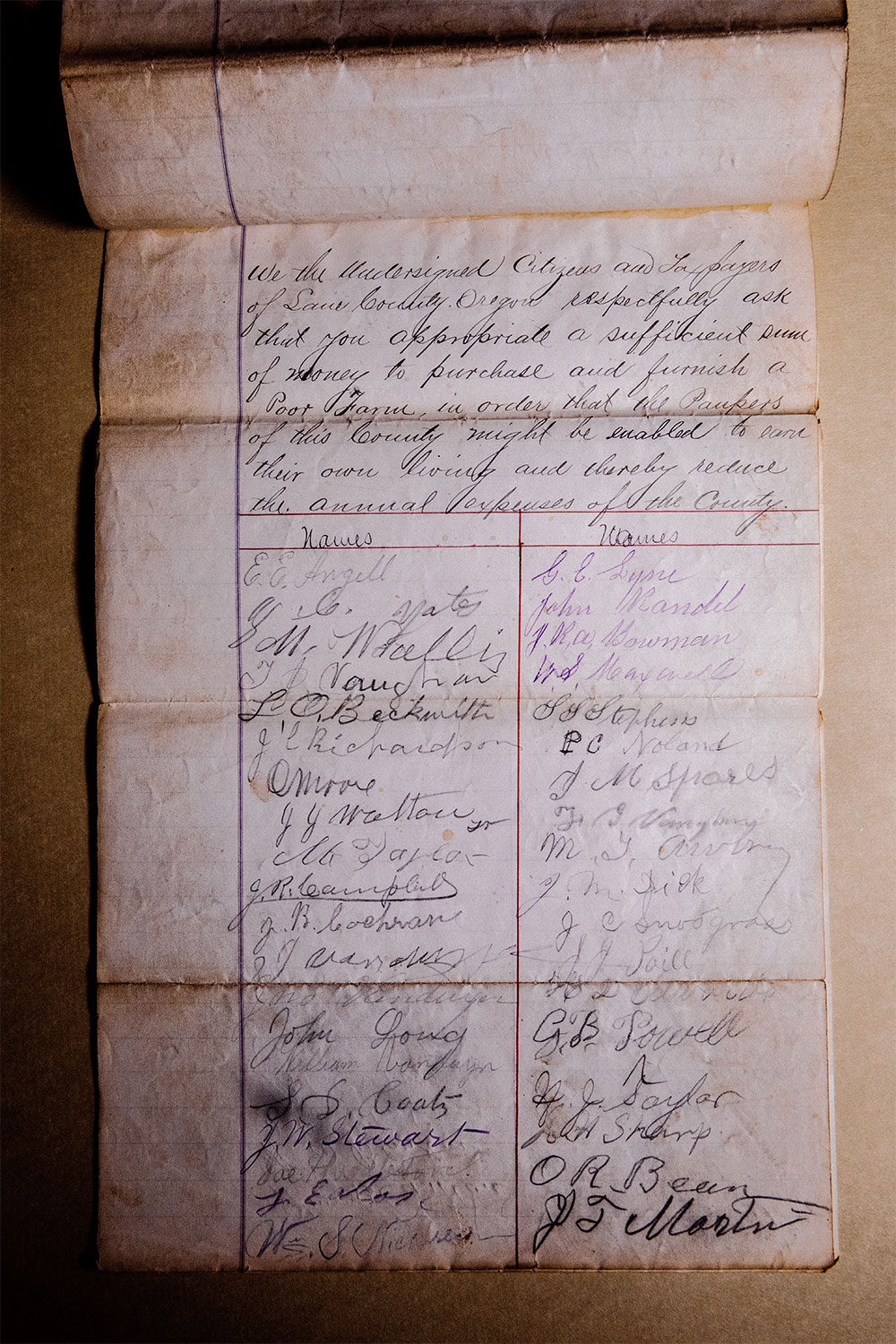

In the 1880s, a petition signed by hundreds of Lane County residents specifically asked county leaders to allot a sum of money to establish the poor farm because of inconsistency in how the county treated the poor, according to a 2009 article by Jerold Williams.

“Citizens and taxpayers of Lane County respectfully ask that you appropriate a sufficient fund to purchase and furnish a poor farm in order that the paupers of Lane County might be enabled to earn their own living,” the letter reads.

The petition was signed by prominent business leaders, including Thomas Hendricks, a banker who helped establish a public library and the University of Oregon — and donated much of the land that is now Hendricks Park.

County residents thought that if the poor were given a place to work and earn money, they might integrate back into society and the county could pay less to its monthly poor fund. The poor fund went towards services such as medical care for the poor and train tickets for stranded travelers.

When the letter was written, Lane County’s population was 9,411. By the time the poor farm was established, that number was nearly tripled.

In the early 20th century, old city ledgers show, Eugene also had a budget for widow’s pensions, which allocated money for non-working widows based on the number of children they had.

Sometime after 1884, postmaster and physician Benjamin F. Russel used his own private home as a place to care for the unhoused. The house also served as a clinic, where Russel practiced medicine. His wife, Maggie, helped him run the home.

It wasn’t until 1910 that the Lane County Poor Farm was created.

County commissioners purchased an 87-acre farm off of a northern section of Coburg Road, which today is County Farm Road. The property was a mile south of the McKenzie River.

The main farmhouse on the property was built for about $127,841, in today’s dollars. They also built a water tower so the house could have plumbing. Around 25 people lived there each month.

When everything was ready to go, they put Dr. Russel in charge, and he signed a contract for $150 a month, promising to care for the poor in a “careful and patient manner.”

The farm functioned like other poor farms at the time. The residents grew oats, wheat, barley and vegetables. There was a barn stuffed with hay to feed all the pigs, cows and chickens. The produce was used to cook meals for the poor farm residents, and operations reports show about $20 of extra supplies was sold each month. The average cost to keep the farm running for a year was about $70,000, adjusted for inflation.

The poor farm transitioned to one other manager and lasted until 1953, when it was turned into a nursing home. Williams’ article notes that the end of the poor farm came amid larger social programs, including unemployment compensation, social security and other welfare opportunities.

As society has modernized, the poor farm grew obsolete, though the values behind creating it still stand.

Terry McDonald, executive director of St. Vincent de Paul Lane County, says every generation has to look at the problem somewhat differently, because homelessness isn’t static.

“Well, first of all, it would be illegal,” McDonald says of the poor farm concept. “The second part is asking the question, ‘Is there a place in the system for giving people an opportunity to live and do something on that site?’ There possibly would but there requires a change in the law.”

The legality of creating another type of poor farm falls under the U.S. Bureau of Labor, which has laws that prevent people from working without pay.

Although creating or replicating a poor farm isn’t a realistic or feasible solution, the idea of coming together to help the poor is ingrained in history.

“The poor farm, and related welfare services, were our welfare program, and we were interested that our tax dollars did in fact serve the poor in our midst,” Williams writes in his article. “Shifting local responsibilities to distant government entities carries the risk of a less humane society.”

No Vagrancy

After the rise and fall of the County Poor Farm, the Eugene-Springfield area had scarcely any services for homeless people. Economic displacement from the Great Depression was a driving factor for the jobless and homeless, McDonald says. With the advent of welfare programs, the federal government took some control of helping the less fortunate.

At the time, people traveling from city to city without a permanent place to live were labeled as “hobos” or “vagrants.” This population would include many World War II veterans who were living in a transition period.

In 1948, the city of Eugene determined vagrancy was getting out of hand, and the Eugene City Council passed an ordinance outlawing “vagrants.” The ordinance defines vagrant as “any idle or dissolute person without visible means of living, or a lawful occupation, who has the ability to work but who does not seek employment…”

The city also considered vagrants as those who roam from place to place without any “lawful business” or who wander “about the street at late or unusual hours of the night.” Many of the indications of vagrancy allude to the life of someone who is homeless.

The ordinance concludes that the enactment of the city law was necessary for “maintenance of the peace, health, and safety of the city and its inhabitants.” It was passed by the City Council and approved by then-Mayor Earl McNutt.

In 1950, the Eugene Mission was established for serving meals to hungry traveling men. It wasn’t until the late 1960s that the Mission transitioned into a shelter.

When the Mission was looking to reopen in a new location, the City Council showed hesitation. According to a 1961 City Council meeting, the Eugene Police Department advised against reopening the Mission closer to downtown, because it would attract “vagrants.” In 1967, the Mission was approved and moved to its current location on 1st Avenue so those who were struggling would have a place to sleep.

The Task Force

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the issue of homelessness worsened due to changes in the social and economic structure of the community and the nation.

The Eugene and Springfield areas were originally settled as timber towns and, for decades, had relied on an abundance of timber.

But when the timber supply began to decline, so did the jobs. The fractured job market was worsened by a national recession in 1980-81 that caused Oregon’s unemployment rate to climb to 11.8 percent. City Councilor Mark Lindberg commented on the issue during a 1982 City Council meeting, saying almost 200,000 homeless adults were roaming the country.

“The depressed timber industry has spawned a new category of vagrants in the Northwest. Hundreds of jobless workers are traveling to urban areas such as Portland, in search of work,” he told the meeting.

Around the same time, the federal government began deinstitutionalizing the mentally ill because of budget cuts and because many hospitals were treating patients poorly.

Tabitha Eck, director of strategic operations for the Eugene Mission, says this forced many mentally ill people onto the streets.

“It’s like the walking dead,” she says of the time. “Folks were institutionalized for a majority of their life, and the doors just shut. The average citizen doesn’t know how to work with the schizophrenic off their medication. We are not equipped and are not educated to do that.”

The issue of homelessness became more complicated, and it took a while for the city to intervene.

“The city and public sector did not perceive homelessness as an issue in the ’70s and early ’80s,” McDonald says. “We closed the mental institutions but we didn’t give an alternative as a nation.”

Although the city didn’t immediately recognize the problem, a growing number of service providers opened up.

The Mission started helping people with addiction and mental illness. White Bird and CAHOOTS — services and crisis response for those with mental and behavioral health issues — were established in 1969 and 1990 for these reasons.

In 1982 Ernest Unger, the director of the Eugene Mission at the time, suggested that the city establish a Vagrancy Task Force to help people on the streets. People in the community and City Council members agreed, volunteering to serve on it.

A year later the Vagrancy Task Force was established, becoming a project that many citizens participated it. It produced “recommendations and strategies to help alleviate the problems of vagrancy and homeless families in the future.”

Some of the recommendations included a detoxification program and the city coordinating efforts to provide housing for the homeless. The prohibited camping ordinance was also born of the task force, although some believed it was unconstitutional because it gave too much discretion to police.

Moving into the 1990s, the task force wanted the city to create a separate homeless camp and reconsider the camping ordinance.

The City Council focused on providing more emergency housing. St. Vincent de Paul began running a shelter in 1990. Throughout the decade, the city created a new homeless committee, which piloted a few different solutions. Some projects, such as creating a car camp, were successful and others, including portable toilets and a home share program, no longer exist.

Looking ahead

Decades after the poor farm, Eugene and other parts of Lane County continue to seek ways to help the homeless. In 2017, a community of 22 tiny homes called Emerald Village was created for low-income renters. For $250 to $300 a month, people in transition or who were previously homeless have the opportunity to live in a mini neighborhood, instead of on the streets.

The Eugene City Council is looking at recommendations made last year by the Technical Assistance Collaborative, a nonprofit consulting firm in Boston, which the city and county hired for more than $84,000 to come up with a plan to address homelessness.

The TAC report, received in January 2019, suggests the city better coordinate outreach services, create permanent supportive housing, develop a new year-round shelter, strengthen supports and to expand and homeless prevention tactics. Completing these recommendations is expected to cost the city at least $2 million.

So far, the county and local donors are funding a 51-unit supportive housing complex called The Commons on MLK, located next to Lane County Behavioral Health. The other recommendations are to be assessed and implemented over the next 10 years.

McDonald argues the TAC report is a static document. Because of the time and money it takes to complete the solutions, he says, the profile and the needs of the homeless community will change.

“Unfortunately, societies are dynamic,” he says. “So I appreciate the degree for which housing is going up on MLK, that’s really good. But I still have a problem this year. I’ve seen twice as many homeless people as I’ve ever seen, and I don’t have a way to respond.”

To change the future of homelessness, it just may take the people of the community coming together once again.

This story has been updated.