Elliotte Cook moved to Eugene in the early ’80s with his brother, Lennard Cook, and his mother, Bahati Ansari.

At Thomas Jefferson Middle School, where he was a sixth-grader, Cook was always in trouble. White kids would say racist things to him, and he’d get into fights in the locker rooms. He was always in the principal’s office. His mother told him he had to stop fighting, even though she understood his struggle being a Black boy.

One day, Cook walked into a classroom and scanned the walls. They were covered with artwork by students.

His eyes stopped on one piece: a rendering of a dead Black man, neck in a noose, hanging from a tree.

Cook ripped it off the wall and brought it to his teacher. “What is this?” he said.

“So?” the teacher replied and shrugged.

Cook took the paper and crammed it into the trash can.

The teacher told Cook to put the picture back on the wall. The classroom erupted in laughter.

Cook ran to the principal with the art, barging past the secretary and directly into his private office. The principal was on the phone. Cook pushed the paper toward him on his desk. The principal rolled his eyes, turned away from Cook and kept talking on the phone.

Cook rushed out, home to his mother where he explained to her what happened.

“That’s enough,” Ansari said.

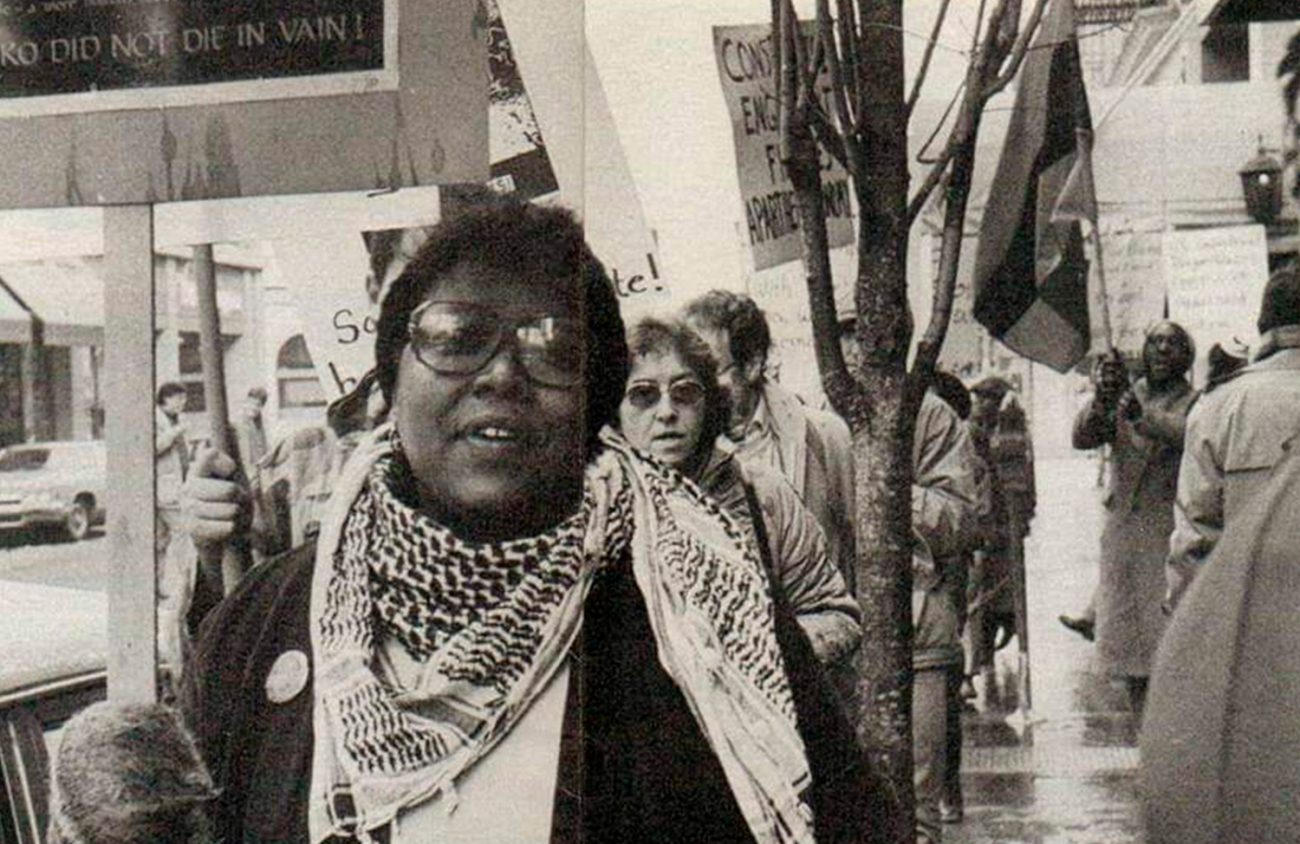

That moment started Ansari’s work of exposing racism and fighting against it in Eugene schools. Her friends and family say that Ansari, who died June 26 at 72 years old, helped Eugene become a more inclusive place by fearlessly discussing racism and how to fight it with anybody who’d speak with her.

Ansari was born outside Chicago in 1948. She was adopted into a farm family that Cook says used her for her labor. Ansari suffered during her childhood, and never told her sons about it in detail.

But she made things work. After Ansari had her first son in 1969, and Cook in 1972, Ansari got a degree at Chicago’s Kennedy-King College, where she studied art and graphic design.

Ansari later went on to receive her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Sojourner-Douglass College in Baltimore, Maryland, after her time in Eugene.

Cook has a memory from his early childhood of sitting in a trash can in a classroom where his mother was taking classes. Ansari had to bring Cook with her to her art class because she didn’t have anybody to take care of him. There was nowhere for him to sit and he was running around, so they put him in the trash can next to his mother. Cook and his Ansari later joked that he was a “trash can kid.”

After Ansari graduated college in Chicago, she moved to Eugene with the kids because she wanted them to be free from the violence of the big city, Cook says. But what awaited them in Eugene was more racism than they’d ever experienced. Chicago’s population is about a third black, while Eugene’s is less than two percent black.

After Cook’s experience with the drawing of the hanged black man, Ansari pulled both her kids out of school. Misa Joo, a friend of Ansari’s and a 4J school teacher, homeschooled the kids. Cook says the school district threatened to put Ansari in jail for not enrolling her children. But instead of putting her kids back in, she got to work.

Ansari talked to civil rights activists, lawyers and reporters in Portland and California to get publicity and support for her cause, all while awaiting action from the school district.

Joo says that while Ansari dealt with this, she also hosted Rosa Parks, who came to Eugene while working on Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign. While in a hotel room telling Parks about her sons’ situation, Ansari broke down crying. Parks offered her support.

The next day, Ansari got a call from the principal of Cook’s middle school, telling her to come in for a meeting. She was nervous, worried that she’d be put in jail and her sons would be taken away.

So Parks gave Ansari protection. Three members of the Fruit of Islam who were Parks’ personal body guards accompanied Ansari to the meeting. The three tall Black men, members of the paramilitary branch of the Nation of Islam, walked with Ansari into the meeting, carrying black briefcases, wearing three-piece-suits and dark sunglasses. One of the men spoke in support of Ansari.

After the speech, the principal, who Joo says was clearly intimidated, said “What would you like us to do?”

Ansari listed her demands for training, education and conversations with staff and students to combat racism. These demands, which the principal and the 4J superintendent were open to, turned into the project of creating the first Racism Free Zones, at Thomas Jefferson Middle School (later Jefferson middle and now Arts and Technology Academy) and Spencer Butte Middle School.

The Racism Free Zone, Ansari’s concept, was an idea that spread across the country. According to Guadalupe Quinn, a Mexican American woman who helped Ansari with her work, the zone included anti-racist trainings, conversations and education about racism and the Black American experience for everybody involved.

“The Racism Free Zone created the opportunity for the students, the teachers, the parents and even the district to become aware of the value of teaching history, of talking about the history and the struggles of Black people in this country,” Quinn says.

Quinn describes a workshop Ansari led with some white 4J teachers in the late ’80s.

Ansari strode into the room, wearing colorful, loose African clothes and a turban. She had strands of beads hanging from her neck.

Ansari asked them “What did you notice about me when I walked in.”

The teachers said they noticed her colorful dress, her turban, her long manicured fingernails, her jewelry.

“Did nobody notice that I’m a Black woman?” Ansari said.

Quinn says Ansari urged everybody to acknowledge race, to acknowledge racism, to not shy away from difficult conversations.

“I think it made people very uncomfortable,” Quinn says. “But what I loved and respected about Bahati is that she didn’t let people dilute it. This was about racism.”

After the initial trainings Ansari conducted to create a Racism Free Zone, she didn’t let people off the hook, Cook says. She’d ask for more trainings, reports and calls with her. Because of Ansari’s persistence, Quinn says the Racism Free Zones became much less racist, more inclusive places.

While Ansari was a mother and activist, she was also an outstanding educator, Eugene City Councilor Greg Evans says. Ansari taught a Black history and identity class for students at Rites of Passage at Lane Community College, a program designed to help people of color that Evans founded in 1996. She connected so well with students, he says, that in one instance, donors gave the program money after observing her class.

Evans, who is Black, says she helped him learn how to survive and thrive in a community with very few Black people, and credits her with much of his success. Evans says she had a persistent style of activism that young protesters in the Black Lives Matter movement can learn from.

“She always had a way of telling people this is not a sprint; this is a marathon. You have to be there not just during the peaks, but you also have to be vigilant during the valleys,” he says. “She was one of those people that wouldn’t let you give up.”

While Ansari passed away in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she moved in 2007 to be with her husband’s family, Evans and Cook say her mark on Eugene remains.

“To anybody who knows her, I’m telling them she is not gone,” Cook says. “She has just left the room. Because everything she’s given will continue to grow.”

Donations and memories can be sent to Elliotte Cook at 3131 Leo Rd SW #C, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87105.