With the autumnal equinox behind us, fall is rushing in the same way spring chases the vernal equinox. Our autumn is what Zen tradition calls “Seeds to Snow.” Sharing north temperate climates, that designation fits us well. It’s time to pull out summer garden plants and put in seeds and starts for the winter garden.

In October 2009 this column mentioned the striking patterns on bigleaf maple leaves as they turn gold and fall to the ground. It is happening as usual, right now, continuing through the end of the month. Anybody who walks through valley bottom woodlands notices their appearance every year. Enjoying valley woodland walks, especially along the Willamette River bank paths, becomes a treasured experience when many favorite upriver forest paths are in a state of death.

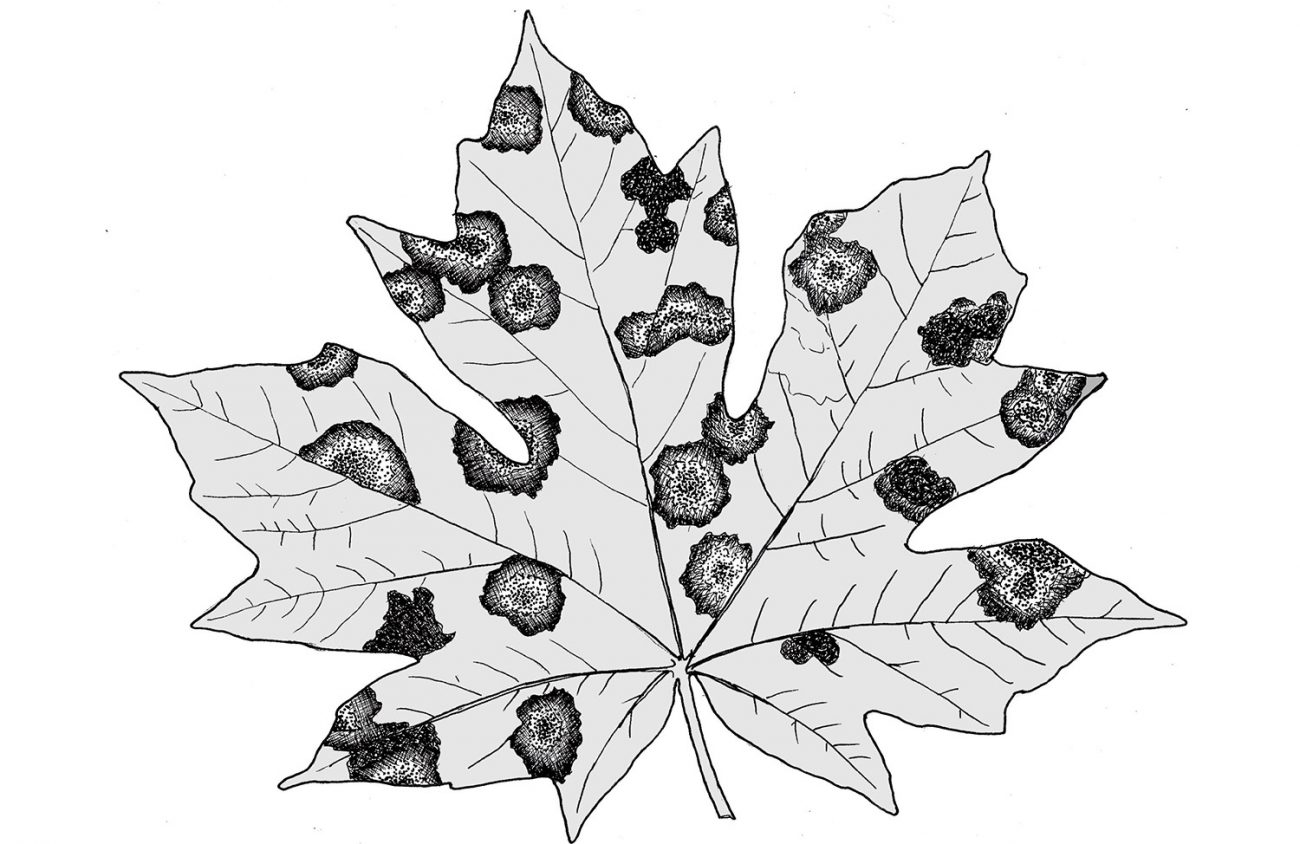

Every fall we find large green-bordered spots on aging bigleaf maple leaves. It is common, although not every tree has them. As bigleaf maple leaves turn yellow, colonies of the fungus Rhytisma punctatum (tar spot fungus) grow quickly. They live inside the leaves, unnoticed, all year. Their function, theory holds, is providing endogenous antiviral security, similar to Penicillium antibacterial capabilities. It’s a symbiosis.

Its life cycle is fascinating. At season’s end, the fungus preserves the last of the green leaf cells to produce spores for the next season. The green ring around each colony does that job. The tiny black spots, building a low dome in the center of origin, are the spore cases for next year’s cohabitation.

David Wagner is a botanist who has worked in Eugene for more than 40 years. He teaches moss classes, leads nature walks and publishes the Oregon Nature Calendar. Contact him directly at fernzenmosses@me.com.