A grainy photo shows now retired Lane County Commissioner Pete Sorenson riding on a horse, dressed as the “Lone Liberal” in the Eugene Celebration parade in the early 2000s. Just as the Lone Ranger traveled through the American West fighting bad guys, Sorenson spent much of his time on the board of county government debating conservatives.

He decided not to seek re-election in 2020, and on Jan. 4, Sorenson’s 24 years as a county commissioner came to an end when Laurie Trieger was sworn in to succeed him. He endorsed Trieger, a fellow progressive who he says was one of the most prepared candidates for the elected office. But if politics are to attract other qualified candidates, it needs to offer a reasonable wage, he says.

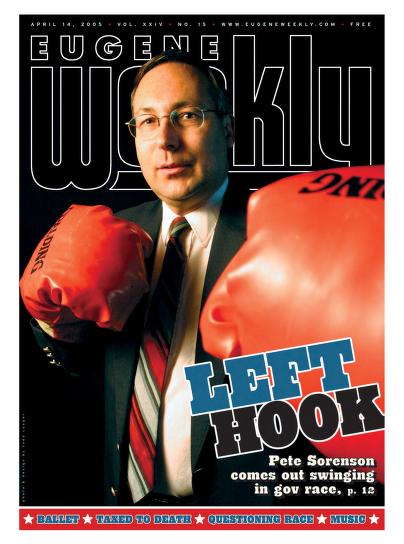

For nearly a quarter of a century, Sorenson sat on the board as it flipped back and forth between conservative and liberal majorities. He’d taken a stab at higher offices but in the end remained on the commission representing south Eugene. There he says he governed well, provided outreach to constituents no matter where they were located and provided leadership during elections.

Before Sorenson was the Lone Liberal, he was one of a crowd of candidates hoping to succeed Jerry Rust, who was on the board for 18 years. “That election was tough because there were nine candidates,” Sorenson says. “I finished first but not enough to avoid a runoff.”

During Sorenson’s first term on the board, he says he was the lone dissenter in a lot of 4-1 votes, which led to his Lone Liberal nickname. “A lot of people who follow politics would say that was the high point of conservative control of the Board of Commissioners in the late ’90s,” he says.

Being in the losing minority doesn’t mean Sorenson has been on the wrong side of votes, though, and he says he made a lot of contributions when he wasn’t on the winning side.

In 2011, the commissioners needed to hire a new county administrator. The board chose to not have any interviews to replace the administrator, Sorenson says, and the conservative majority decided to hire Liane Richardson (now Davis). “Again, I was on the losing side of that vote,” he says. “I pointed out that hiring someone without doing a background check or hiring someone without having a resume or having a competitive process could lead to mistakes.”

From 2011 to 2013, Sorenson says the hire resulted in a lot of executive fighting and lawsuits, all of which could have been avoided with better leadership from the county administrator. And some lawsuits are still being paid out by the county. In 2019, former county attorney Marc Kardell was awarded $228,000 after a federal jury decided his free speech was violated by Richardson.

Richardson was fired in 2013, and Sorenson says the conservative commissioners listened to him when hiring her successor, Steve Mokrohisky, by having a competitive hiring process. “I think the conservative commissioners listened to me because I was right about the unfortunate mistake of hiring Ms. Richardson,” Sorenson says.

Sorenson says he holds two records: He’s attended more than 10,000 hours of Lane County Board of County Commissioner meetings and has been elected to the board more times than anyone else.

But showing up is one-third of the job, he says. Another important part of the job, he says, is to provide assistance to constituents, and he’s proud to point out that he’s written more than 300,000 emails to them. “I’ve helped constituents adopt a baby from India or I’ve helped constituents answer who’s going to pick up garbage on a road. They don’t know which government it is. They just know they’re reaching out to someone to try to help them, and if they’re in my district I try to help,” he says.

As an elected official, he says he sees a need to provide leadership on issues like promoting ballot measures or supporting candidates. “I’ll write op-eds. I’ll speak out,” he says.

Sorenson did run for higher office. Before he was elected to county commission, he explored a campaign for U.S. Congress when Congressman Peter DeFazio considered running for Senate. When DeFazio decided not to run for Senate, Sorenson stopped his campaign for Congress. As a county commissioner in 2006, Sorenson ran against Gov. Ted Kulongoski in the May primary but lost.

The only time Sorenson faced a tight race for re-election for his seat was in 2012 when Andy Stahl ran against him. Sorenson still won. Although Stahl is a progressive, that race does show how south Eugene voters weren’t swayed by conservative political shifts of the past decades that influenced other seats on the board, such as the Tea Party and Trumpism.

Before Sorenson was a commissioner, he served two terms as a state senator but couldn’t run for a third term because of voter-imposed term limits. The politics of campaigning killed his law business, he says, and he was working full time in Salem but only getting a part-time salary. Elected offices need to provide a reasonable wage to attract working people, he adds, “We cannot run them on an agrarian model of volunteerism that we might have been able to do in the 1800s.”

Whether serving on a board of education or in the Legislature, it takes time, money and work to be elected and then serve, he says. For everyone to have a shot at serving in politics, he says money needs to get out of the system. The Lane County Board of County Commissioners does at least offer a living wage, he adds.

Sorenson announced he would not run again during his swearing-in ceremony in 2017 to give candidates a chance to prepare for the 2020 election, which Trieger won, beating Joel Iboa, in a November runoff. Sorenson says his old seat is in good hands. “You judge leaders by the kind of successors they leave, and I think it’s really good that she’s going to be our commissioner for south Eugene,” he says.

During Sorenon’s final board meeting, Commissioner Jay Bozievich, who’s now basically the lone conservative, said he and Sorenson have been on the same side of issues at times because they look with a legal lens. “That’s the integrity we have,” Bozievich said.

Sorenson says making himself a lameduck commissioner gave him time to ponder an exit strategy. So after nearly 50 years of work in the public policy world that began with a job in former Congressman Jim Weaver’s office, the Lone Liberal will ride off into the sunset and use his law degree to help Americans file federal public records requests, as well as spend time with his family.

“I intend on doing Freedom of Information Act work to help journalists, authors and nonprofits get records important to them,” Sorenson says. “That work is meaningful to me and needs to be done.”

This article has been updated