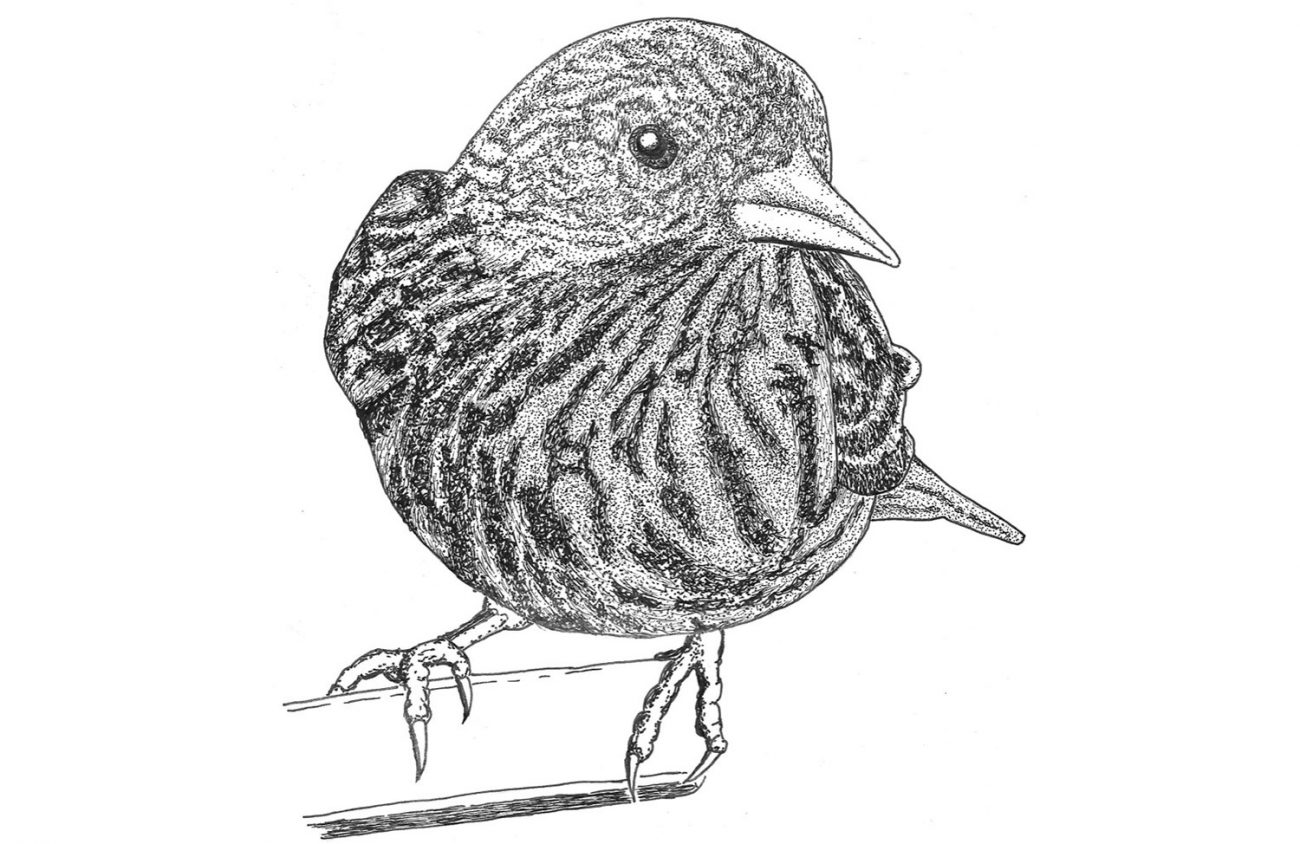

Suddenly, in the third week of May, pine siskins disappeared from our yard. Ever since last year’s Labor Day fire, our feeders have been crowded with unusually high numbers of goldfinches and other small birds. None were more dramatic than the flocks of pine siskins. This past fall and winter their numbers grew so much they dominated the feeders, a dozen or more at a time. Concomitantly with this surge in numbers came the spread of salmonella infection among the pine siskins.

This salmonella outbreak occurred throughout the Pacific Northwest. I found dead birds in our garden and had to euthanize some who sat shivering on the feeder, unable to fly away. Mortality was so high that the Audubon Society urged us to put away our feeders for a couple of weeks. The idea was to prevent transmission by forcing them to hunt natural seed sources individually. I put away our finch seed feeders and kept a platform feeder out of sight for most of the winter. After a recommended pause, I put seed feeders back up. The pine siskins returned in former numbers. Thankfully, infection rate was clearly less. Migration day has arrived now and they have gone away to nesting grounds where, hopefully, the salmonella infection will be reduced to normal background rates.

The global spread of COVID-19 among humans has significant parallels. Humans have a significant advantage: a vaccine that prevents infection. But birdbrains among us refuse vaccines and cluster in spreader situations. Lord save us.

David Wagner is a botanist who has worked in Eugene for more than 40 years. He teaches moss classes, leads nature walks and publishes the Oregon Nature Calendar. He may be contacted directly at fernzenmosses@me.com.