Speaking with Jordan Schnitzer over the phone, I hear an urgency about putting a grant together for a Black Lives Matter art exhibit.

Every group, no matter their culture, ethnicity or gender, has been a target for some other group, he says. It’s a remarkable statement but one that rings true, especially considering the history of the U.S. — or of Eastern Europe or Russia, where Schnitzer’s maternal grandparents are from.

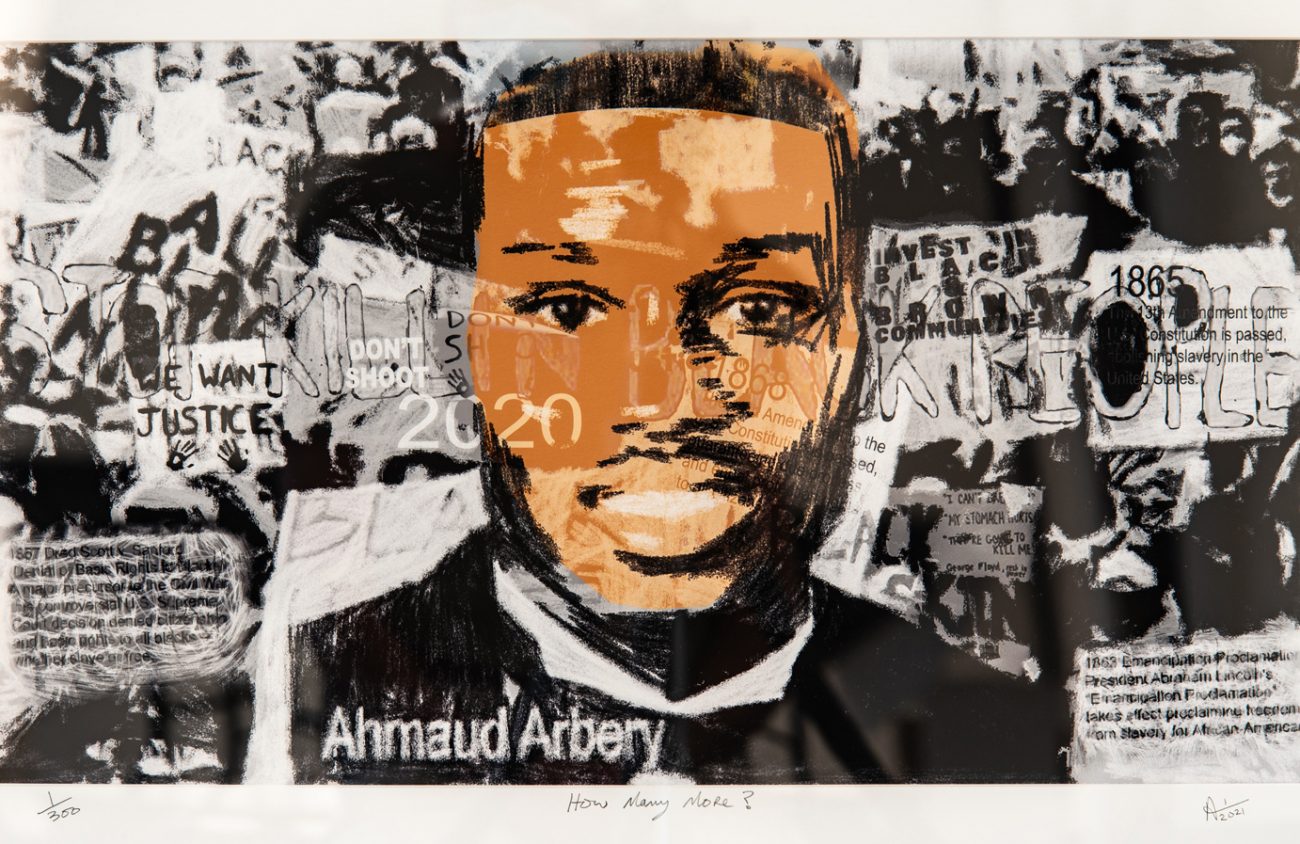

Funded by Schnitzer, a Portland real estate developer and avid art collector, work by 20 artists goes on display July 3 in the Black Lives Matter Artist Grant Exhibit, which runs through Nov. 21 at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon. The artists were chosen by a panel assembled by the museum and the Lyllye Reynolds-Parker Black Cultural Center on campus.

The artists are mostly from the Eugene area, though some also are from Bend and Ashland. They are an eclectic group in terms of culture, race and ethnicity, though the subject matter of their art, relating to Black Lives Matter, ties them together. They have come to Oregon from across the country and around the world. And though the four artists highlighted in this story all work with different media, most of the work in this show is photography or video based.

The artists are John Adair, Mika Aono, Gabriel Barrera, Gabby Beauvais, Kathleen Caprario and Gregory S. Black, Marco Elliott, Marina Hajek, Jasmine Jackson, Mya Lansing, Ana-Maurine Lara, Anthony Adonis Lewis as well as Stormie Loury, Malik Lovette, Tumelo Michael Moloi, Naomi Meyer, Artemas Ori, Michael Perkins, Josh Sands, Aaron Thompson and MO WO.

Schnitzer created the grant and three exhibits in partnership with the Jordan Schnitzer Museums of Art, which are located at Portland State University, Washington State University and at the UO. The 20 artists at each of the three museums were each awarded $2,500.

Moloi, True, Adair and Aono, four of the 20 grantees funded by the grant whose art is showing in Eugene, used their funds to address racism and its associated effects. Their work is done in different media and carries with it different tones. But each puts forth a message of strength, unity and hope, steps from which to carry on conversing and, hopefully, towards creating a more just and equal overall society.

Seeking liberation

Stormie Loury, who also goes by the name True, is originally from Chicago but has lived in the Pacific Northwest for 21 years. She describes herself as “an Afro-futuristic social political multimedia activator who focuses on themes of Black Liberation.” Her three works in the show, all done in felt textile, reference a “survivalist perspective,” according to her artist statement:

See ‘they’ started too soon,

with no wisdom

‘they’ rose

‘their’ feet bruised from

the money motivation.

With no foundation ‘they’ rise.

So keep rising fool

Cause what ‘they’ searching for

We’ve always had.

What “We’ve always had” is a particular kind of wisdom or strength which the artist describes as necessary for the “African American” (quotes are hers) mind to survive in the “white” world; a strength required not just to survive but also to maintain cultural roots.

Loury’s artwork “Survivalist Perspective II: Her Blood Tears” represents a “3rd eye” that helps people to persist beyond the physical and emotional sacrifices they’ve had to endure. In her view, it’s this third eye that assists African Americans in maintaining their sense of culture and identity.

Collaborative dance

Another grantee, Tumelo Michael Moloi, moved from South Africa to the U.S. to perform with Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas. He tells me about the culture shock he experienced one Martin Luther King Day: Cirque du Soleil asked non-Black performers in the troupe to step aside for a photograph. Moloi was surprised that white people were being excluded from the picture. He says in South Africa, when Nelson Mandela came to power, he could have sought revenge and excluded enemies but generally led by “treating everyone the same.”

In other words, celebrating equality shouldn’t be a Black thing. Moloi says, “Everybody has to work together.”

Moloi wound up in Junction City because, as he says, “I fell in love.” His wife’s family has a farm where he now lives and works, and where his father-in-law allowed him to convert an outbuilding into an artist’s studio.

Though he hasn’t found much opportunity in Eugene for the artistic collaboration he has done elsewhere, he views living here as an opportunity to start over, to do something new and more personal. Sharing the video with me that he submitted to apply for the BLM Artist Grant, I see a highly collaborative piece that couldn’t have been led by anybody else. He choreographed via Zoom with artists in different countries, combining music, dancing, news footage and even references to hand washing in rhythm, marking the pandemic during which it was made.

Beginning with footage of Black workers in South Africa during apartheid, the video splits the screen to show three dancers each doing the same dance in the U.S., in South Africa and in Brazil.

One of the dances he includes in his performance is called “Gumboot.” The dance originated in the mines of South Africa as a way for workers to communicate among themselves. Miners were from different cultures and spoke as many as 11 different languages, Moloi says. But when they stomped their rain boots twice, for example, it meant the bosses were coming.

You could say that Moloi’s entry in the exhibit (or entries — he’s not sure if one or both of his videos will be shown), functions as a call, too. First, he says, people have to acknowledge the reality of the Black experience. Having been around for the last part of apartheid, he believes in the adage that the first step toward fixing a problem is acknowledging it exists.

Photography

John Adair came to Eugene from Kansas. A full-time Lane Community College student and a part-time photojournalist for the school’s paper The Torch, he also works for the fairly new Double Sided Media, a digital publication that delivers “Heady Writing From The Streets of Eugene, Oregon.”

Adair photographed the riot that broke out in Eugene last May. It was totally by accident, he says. He happened to be at his studio, which was on 7th Avenue at the time. The first thing he heard was fireworks then later saw the dumpster fire. He had his equipment so he went down and took pictures.

His photographs from that night are available for viewing on his website, JohnAdairPhotographs.com, under the series titled “George Floyd Riot of Eugene, Oregon.” They capture stunning moments of frustration, violence and confusion.

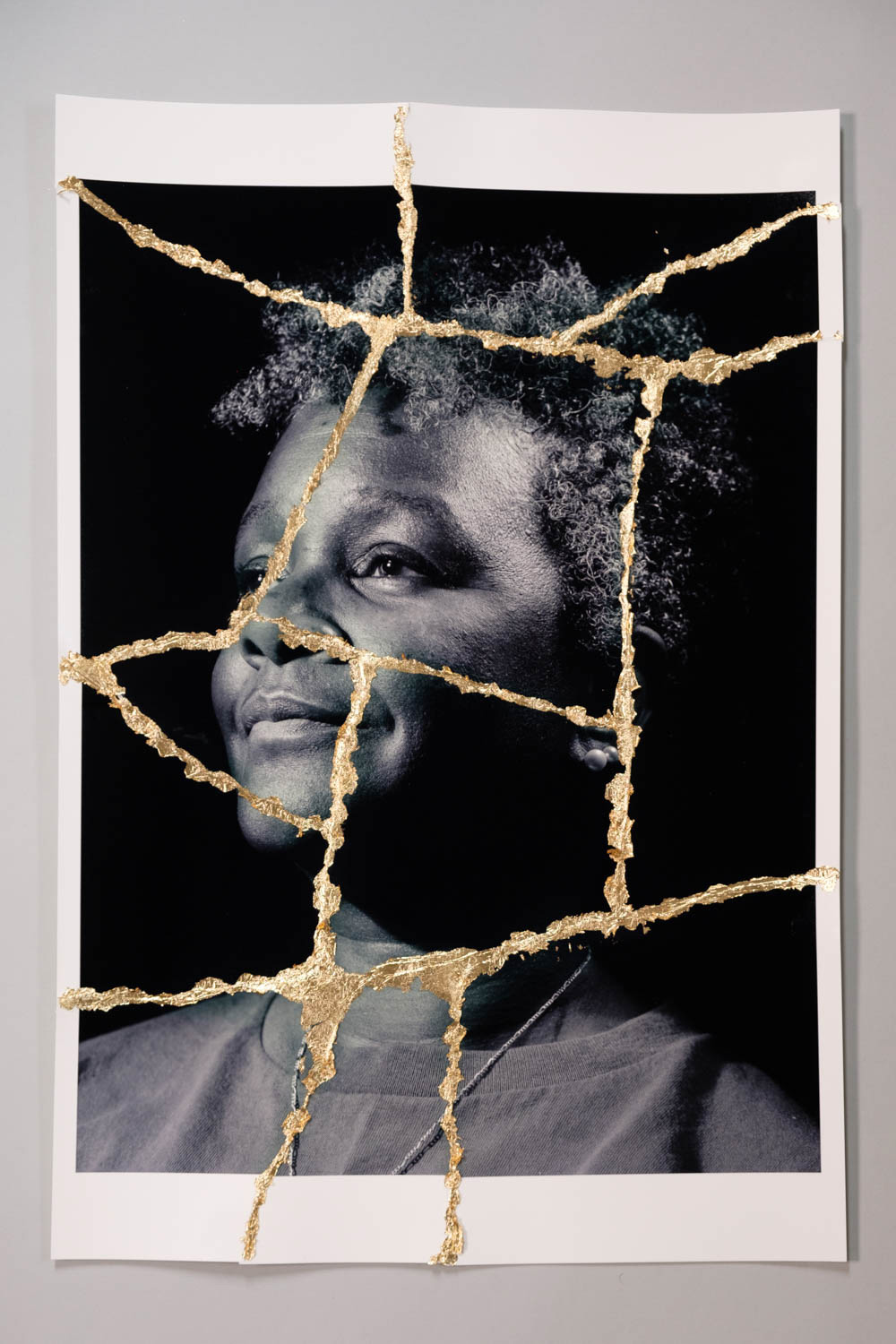

Adair chose a more controlled environment for the setting of his BLM Artist Grant work. Going for a “personal take” this time, he took photographs of his family. Six photographs from his series titled “Black and Gold” are featured in the exhibit.

He spoke with family members from whom he’d been feeling disconnected, and he says the experience made him feel closer to them. Before he took their portraits, he asked each relative to relate an experience they had with racism. In each instance, the first racist experience his family encountered occurred during childhood.

The photographs are printed in black and white. The gold in the series “Black and Gold” is gold leaf. Borrowing from a Japanese practice used to mend broken pottery called kintsugi, Adair tore his portraits and then glued them back together, lining the “scars” with gold.

Referencing the Japanese aesthetic, he says that we can fix broken things and still find them beautiful. His relatives recovered from the racist incidents, he says, moved on and now live lives that are not defined by fear.

Print performance

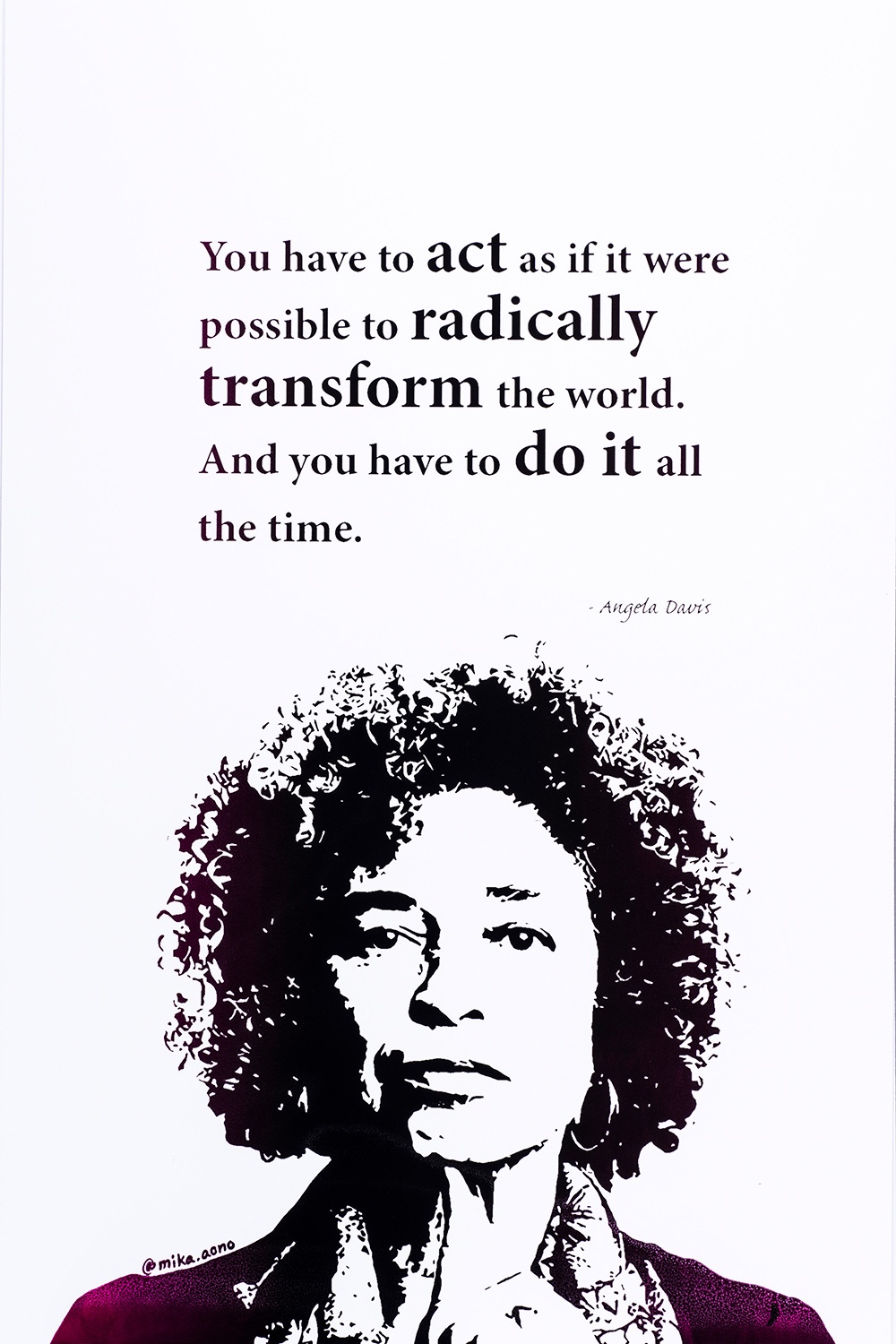

Recipient Mika Aono is from Japan. She studied art at LCC and the University of Oregon before earning an MFA in printmaking from the San Francisco Art Institute. She has lived in Eugene for 19 years and manages the print shop for the UO’s School of Art and Design.

When she was younger, Aono went to Nepal to work with the Red Cross, and she ran a small fair-trade business in Peru. In her life outside of art she says she sometimes feels helpless to effect change.

But as a printmaker, she says, “I do what I can.”

Using funds from her grant, she held two “print performances” at Eugene Contemporary Art’s ANTI-AESTHETIC gallery. She says performances are important because they invite people to gather.

Her BLM Artist Grant work was inspired by the signage that sprang up around town these last years, on people’s lawns and in store windows, calling for peace and for unity. She especially liked the BLM slogan, “We’re all in this together.” It makes her feel happy, she says. So when she was chosen as a grantee, she knew she wanted to put more positive signs out into the community.

Though she will have prints in the exhibit, the assistance she received from the grant for materials enabled her to give posters away, too. She gave away lots during the performances. In fact, she ran out of posters. She then printed more and ran out again.

Creating a conversation

Schnitzer has seen images of the art ahead of the show. “Wow,” he says.

The one word response takes me aback. It’s quite different from the eloquent manner in which he’s been discussing the topic of racism, and of art in the abstract. “Artists force us to look at our values,” he starts off. “Are we the people we think we are? Do we practice what we preach?”

Then in response to the art, it’s just “Wow.”

But isn’t that the way it is when an artwork grabs you? Then, if you want to talk about it, you have to think about your response. You have to find the words.

That’s how this grant started for him: with a desire to generate words. He has more than 19,000 works in his personal art collection. His focus is on contemporary artists, many of whom are people of color. He could have easily drawn from his collection to support an exhibit that stimulates dialogue. But last year, when BLM protests were taking place in Schnitzer’s hometown of Portland, he wished more conversation was taking place as well.

Rather than looking at art made in the past, no matter how excellent, he says, he created this grant to encourage art to be made to address this moment in the BLM movement.

The Black Lives Matter Artist Grant Exhibit runs July 3 to Nov. 21 at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on the UO campus. JSMA is open 11 am to 5 pm on Saturdays and Sundays. A celebration of the BLM Artist Grant program at JSMA is scheduled for 5 to 7 pm Thursday, July 8.