Active walk. Get your heels down. Sitting trot. Quiet your hands. Posting trot. Switch the diagonal. Right lead canter. Atta-girl.

These equitation colloquialisms are second nature to anyone familiar with the sport of horse riding. With a slight shift in weight in your seat and a readjustment of the leg at the flank, your horse makes a smooth transition from walk, to trot, to powerful canter.

But who normatively gets to sit atop of these majestic ungulates? Take a look at the advertisements for most mainstream equestrian products, and you will have your answer.

There is a hegemonic narrative of who rides horses, a narrative that has been written and rewritten with the intention of highlighting some identities while erasing others. We saw these narratives play out across the American West, with historians now estimating up to one in four cowboys were Black. This reality flies in the face of the noticeable absence of African Americans from cowboy narratives compared to their John Wayne-esque counterparts.

The stories that we tell are the stories that persist. The very real repercussions of this biased narrative-making are the myriad barriers that historically marginalized identities confront when attempting to gain entry and acceptance into the horse-riding world.

The high costs of instruction and riding gear, unwelcoming barn communities and feelings of isolation all do the work of ensuring the mainstream horse-riding community stays predominantly able-bodied, wealthy and white.

As a rider myself since I was 12, I have had my fair share of experiences that highlight the exclusion inherent in modern day horse-riding communities, from having to take out school loans to pay for college Intercollegiate Horse Show Association team membership to most recently having my hopes of auditioning to be a rodeo flag girl at the 2022 Eugene Pro Rodeo being dashed because I do not have my own horse to ride.

“It’s really just for people who do that,” I was told when I inquired about the rodeo audition process. I guess that counts me out.

Fortunately, a small nonprofit in Lane County has begun the work to disrupt this narrative. In its original conception, Solid Strides was founded in 2017 by Alison Weston, now a board member, as solely a horse welfare organization. Avid equestrian Katie Ebbage, looking for her opportunity to create access and find her lane in the social justice movement, took the reins in 2019 and revamped the organization to focus more on creating access — including advancing diversity, equity and inclusion in the horse-riding world.

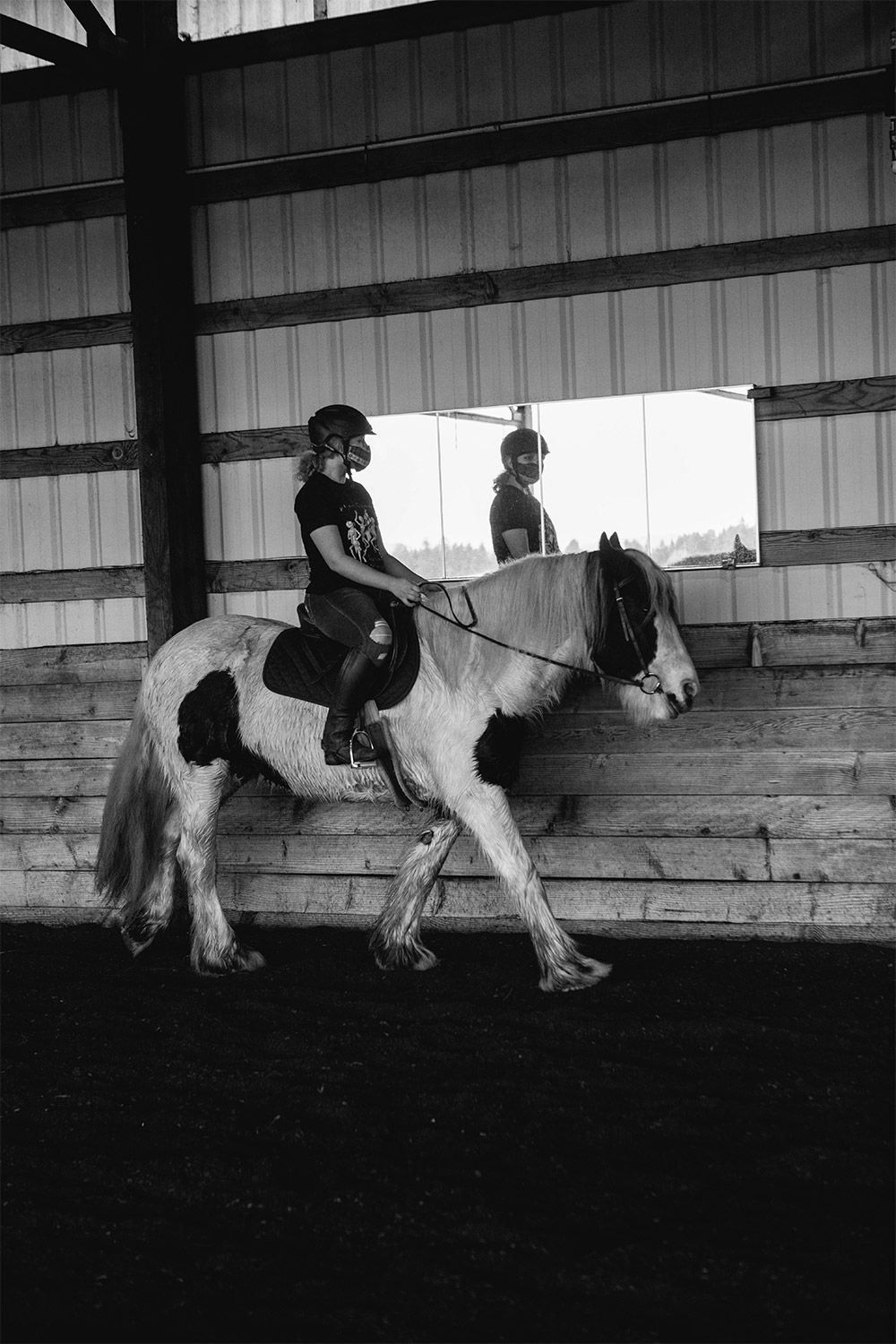

Nestled in the forested foothills of central Willamette Valley, today Solid Strides is a year-round nonprofit horse welfare-based research and educational organization seeking to reduce barriers to entry for historically excluded riders and provide evidence-based instruction to participants of all backgrounds, ages and riding skill levels.

With an organizational mission resting at the intersection of horsemanship and social justice, Solid Strides is an anomaly for Lane County, a region sporting a non-white population of just 14 percent.

The new and improved Solid Strides hit the ground running with the help of a generous individual donor this past summer. There were four one-day introductory camps for Black, Indigenous and riders of color, co-led by Willamette Racism Response Network, allowing prospective riders to get their toes wet in the world of horseback riding.

Following this series, and with support of a K-12 Summer Learning Grant from Oregon Community Foundation, Solid Strides served 45 students with 16 hours each of instruction in low-barrier summer camps. The camps educated students on a variety of topics, including horse lifestyle and nutrition, anatomy and physiology, breed types, gaits, equine behavior and movement as well as equipment, horse and human posture and, finally, riding skills.

With this programming, Solid Strides provides the rare opportunity for riders of all identities, including riders of color, to connect with one another and foster a sense of belonging sometimes absent in less diverse barn communities.

“I grew up in Eugene. When I was 5 years old I knew I wanted to be a cowgirl,” says Jodi Youngblood, board member for Solid Strides and a longtime rider herself. Similar to other riders, the costs of lessons and horse upkeep were very expensive and were a barrier to Youngblood’s progress and development as a horsewoman.

But beyond financial barriers, the sociocultural barriers of lack of diverse representation further isolates underrepresented riders and negatively influences feelings of belonging in the equestrian community. “In anything you do, you want to feel included. You want to feel welcomed,” Youngblood explains. “As a Black woman growing up in Eugene in the ’80s, I never saw anyone that looked like me on a horse.”

Youngblood got involved with Solid Strides when she saw Willamette Racism Response Network advertising its one-day BIPOC Introductory Camps. She eagerly reached out and inquired about volunteer opportunities. As a descendant of Pearlie Mae Washington and the daughter of the first Black man born in Eugene, Youngblood got renewed hope from her engagement with Solid Strides because a younger generation has access to opportunities that did not exist when she was growing up.

“I’m excited about Solid Strides because it provides opportunities for historically marginalized youth to be involved in the sport. It teaches responsibility — horses hold you accountable. If I had programs like this when I was a kid, it would have kept me out of a lot of trouble,” Youngblood says.

From the stellar horse-welfare based quality of programming to offering an inclusive sense of community, Solid Strides is making its mark in Eugene by keeping passionate students engaged and finding ways for them to stay involved in the sport. It was this exact mission that drew me to Solid Strides in the summer of 2021.

I have since become the organization’s assistant program coordinator, designing culturally responsive lesson programs, recruiting new riders of color from the Lane County community, and developing public-facing materials about our programs and sponsorship opportunities.

In addition to the one-day BIPOC Introductory Camps and low-barrier summer camps, Solid Strides also organized two events with Kids for the Culture and Willamette Racism Response Network, where horse activities were combined with Black Cowboy Culture. This holds particular significance; the history of cowboy culture in the U.S. is steeped in racism and exclusion.

In the latter half of the 19th century, entrenched anti-Blackness, reinforced and institutionalized by local and statewide exclusionary policies, restricted the growth of Oregon’s Black population. There were barely more than a thousand Black people in the state, with even smaller numbers in rural areas. Some of these isolated rural areas were “sundown towns,” where being out after dark while existing as a Black person carried deadly consequences. As a result, 19th-century Oregon saw very few African Americans working as cowboys, according to the Oregon Historical Society.

The emergence of the cowboy as a cornerstone of American entertainment at the turn of the 20th century opened up new opportunities for African Americans to participate in cowboy culture. Though still subject to racial discrimination, they finally had opportunities to showcase their skill on horseback.

Solid Stride’s Black Cowboy Culture programming highlighted this complex history, amplifying and discussing the cultural appropriation and inherent racism in stories like the Lone Ranger and his Native American sidekick Tonto, as well as George Fletcher, who came to Oregon at the turn of the century and would later become one of the most famous Black riders of Oregon’s most celebrated rodeo, the Pendleton Round-Up.

Katie Ebbage’s work with Solid Strides is also leaving a lasting impact on low-income families of color. “I’m a single parent with limited resources,” says Alicia Johnson, whose 13-year-old daughter Lizzie got back into riding after participating in Solid Stride’s summer programming. “When Lizzie was doing lessons as a kid, I was doing barn chores to pay for her lessons. When these workshops started, the financial barrier was brought down. Without that, Lizzie would not be riding horses.”

Johnson was fortunate to have ridden horses growing up and wanted the same for her daughter, who was in the saddle as early as 4 years old. “Horses saved my life when I was a teenager,”Johnson says. “Everyone should have the opportunity to experience that and develop a bond.”

For the Olalde family, Solid Strides provides a sanctuary from the disruptive isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. “My daughter has always loved horse riding and that has been one of her major passions,” says Elisa Olalde, mother to 10-year-old Sai. “When COVID happened, everything stopped. We were thinking about how to keep feeding ourselves and our souls.”

The two resolved that horse riding would be a good fit as it was low risk and could also feed Sai’s passion. It quickly turned into something that they both loved. Sai began with Solid Strides at the end of last summer and, with financial support from Sai’s grandparents, began participating in regular lessons once a week.

“It’s been really great for her confidence. I could really see a big shift in her skills and how much more she was able to do on her own,” Olalde reflects. For Sai, the leadership skills she’s been able to develop have been invaluable: “I made a lot of new friends and I was sort of an experienced rider so I got to teach other riders,” she says.

The organization looks to the future with optimism, prioritizing getting youth into regular lesson programming to ensure students have the opportunity to continue to develop their skills as equestrians. Fundraising for scholarships and future programs is essential to advancing the organization’s mission of reducing barriers to entry by offering low cost lessons and programming. Other priorities include offering adult programming, including culturally specific programming, and building partnerships with other community organizations.

“Horses have so much to teach. In addition to riding skills, working with horses creates the opportunity to learn innumerable life skills that translate to improved self-awareness, relationships, communication and valuable school and job skills. This is not a resource that should be limited to those with the social and economic means to participate,” Ebbage says.

She hopes a strong community of support will keep the organization on its feet, allowing it to continue the important work of diversifying the equestrian world through low-cost opportunity and community-building.

Aimée Okotie-Oyekan is a land use planner, storyteller, equestrian and passionate environmental justice advocate working as the assistant program coordinator for Solid Strides. For more on Solid Strides go to KatieEbbageEquestrian.com/solid-strides