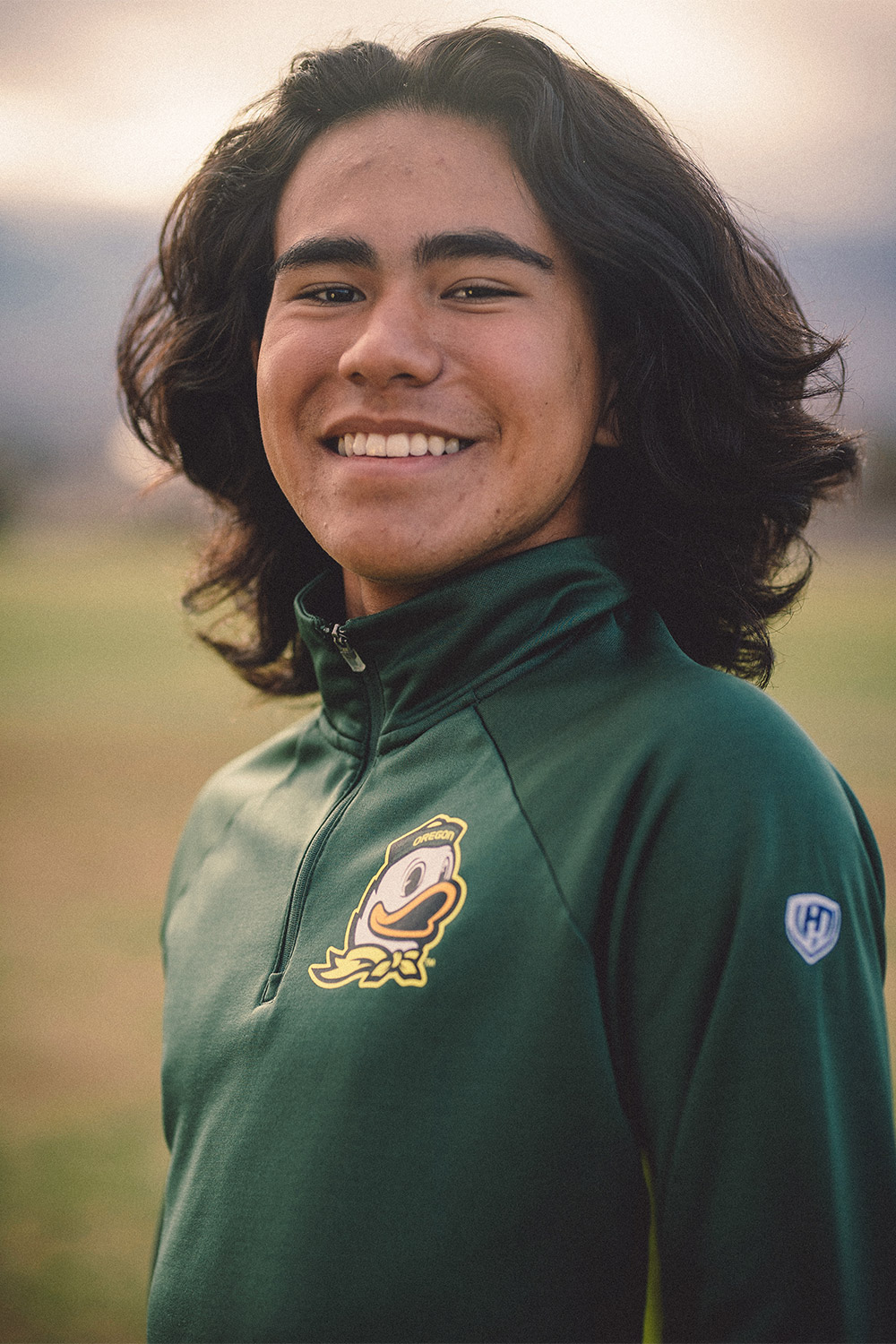

High school runner and Yerington Paiute tribe member Kutoven “Ku” Stevens remembers his most recent trip to Eugene because it was the day he committed to run for the University of Oregon, his dream college.

Accompanied by his family, as well as a team of documentary filmmakers, Stevens had a tour of Hayward Field and then headed outside to take a breath of air, Stevens tells Eugene Weekly.

“I took a knee and sat down for a second. It was hitting me hard,” he says. “I’ve worked so hard for this. So many people that got me to this point. All the training. All the hours. And finally, I’m here. It was a moving moment.”

Enlarge

Stevens isn’t the typical high school athlete heading to the UO. A resident of Yerington, Nevada, population 3,137, and member of the Yerington Paiute tribe, he’ll be one of the few Native American athletes who have ever competed for the UO. In getting there, he’s faced the trials of competing as the only runner on his high school team.

Throughout his running successes, Stevens has kept his ancestry on his mind, which led to a race he organized in remembrance of his grandfather who escaped an Indian boarding school in Nevada and inspired the documentary film Remaining Native.

“When you’re born in a community like I was, you want to get out and make a change and make a difference,” he says. “Through my running, I figured that’s the way I could make my mark on the world. I could go out there, be noticed and inspire other people to be active.”

Stevens started running competitively in middle school. As a fifth grader, he says, he was considered too young to compete, but the track coach saw his running talent and made an exception for Stevens, allowing him to compete against sixth graders.

It was around that time when Stevens heard from someone that the UO was the best place for running. “I was like, really? All right, then I’m going to go to UO someday,” he remembers. “It was from that moment on that I made a promise to myself, and I have to hold myself to it.”

That promise is what kept him dedicated to running and working out, he says, even when his high school wouldn’t fund a one-man team.

Enlarge

As a junior in high school, Stevens was the lone runner on the Yerington High School cross country team, which didn’t have a coach. He designed his own workouts and “flew blind,” he says. With one person on the team, his high school wouldn’t provide transportation to races, so he says he worked a part time job for gas money. Somewhere in between school and work, he found the time to run about 60 miles a week. “It was rough for sure,” he says.

Despite the lack of resources, in May 2021, Stevens won a track and field regional title as an individual in the 2021 Nevada Interscholastic Activities Association Northern 2A Region Championships.

Still running for Yerington as a senior, Stevens started training with the Damonte Ranch High School team in Reno, an hour from his home. And he’s continued to dominate as an individual. On Nov. 9, 2021, Stevens won a cross country state individual title, and on Jan. 31, he was named a Gatorade Nevada Boys Cross Country Player of the Year.

When Stevens moves to Eugene, he says, he’s an “invited walk-on,” meaning the UO didn’t award him one of its NCAA scholarships. He says the UO told him that if he wins races and proves himself on the track, he can then get that scholarship from the university. During the fall, he’ll run cross country, and in spring, track and field.

Running isn’t just a sport for Stevens. He’s used it to raise awareness of Native American issues. And one book has helped fuel that drive.

Enlarge

Stevens says his father recommended the book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, by Dee Brown, a recount of American history through the lens of Native Americans, which he listened to an audiobook edition of while training.

“My dad wanted me to read the book at a young age because he said it also impacted him,” Stevens says. “After he read that he was mad and angry. But the best way he could get back at the people he was mad at was to get educated, because an educated Native American is a dangerous Native American.”

Stevens says reading the book made him mad, too. And in 2021, he took on the goal of educating the running community about Indian boarding schools.

Indian boarding schools were established in North America with the intent of forced assimilation into Western culture. In the U.S., the federal government removed Native American children from their families to attend the schools. Children had to speak English and adopt Western names, and many children never returned home, according to National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit whose mission is to understand and address the ongoing trauma created by the U.S. Indian Boarding School policy.

Stevens organized the Remembrance Run, a 50-mile run that started on the grounds of the Stewart Indian School, a boarding school that ran from 1890 to 1980. Stevens’ great-grandfather, Frank Quinn, attended the school in 1913 when he was 8 years old and escaped the school by foot three times, running 50 miles through the Nevada terrain.

Stevens says his father always wanted to hike those 50 miles to experience what his grandfather went through. The two were inspired to turn that into a run after news broke about mass graves found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada. Stevens says that a lot of people didn’t know that those sort of boarding schools existed, so they hosted a run to educate the public about the history of the schools.

The race attracted a lot of media attention, from regional news outlets to the larger publications like Runner’s World and The New York Times. It also caught the eye of an upstate New York Native American filmmaker, Paige Bethmann. The filmmaker and her team — She Carries Her House Productions — have been following Stevens around at track meets and filming the Remembrance Run as well as his trip to Hayward Field for a documentary called Remaining Native. “I never thought it would happen this young,” he laughs. “Maybe later in life when I’d done something cool and someone would record me for it.”

Enlarge

As Stevens ran through Nevada landscape for the Remberance Run, a route with about 2,000 feet of elevation gain and temperatures in the 90s, he says he thought about his great-grandfather’s journey back home as a child, leaving a place that was trying to erase everything about you.

“It was a lot of emotions, especially around the end,” Stevens says. “I remember crossing this hill and looking upon my valley, putting myself in the shoes of an 8-year-old coming home. Maybe seeing your family there working, doing whatever they’re doing and feeling the sense of relief that you made it.”

For more information about Remaining Native, visit RemainingNativeDocumentary.com.

A Note From the Publisher

Dear Readers,

The last two years have been some of the hardest in Eugene Weekly’s 43 years. There were moments when keeping the paper alive felt uncertain. And yet, here we are — still publishing, still investigating, still showing up every week.

That’s because of you!

Not just because of financial support (though that matters enormously), but because of the emails, notes, conversations, encouragement and ideas you shared along the way. You reminded us why this paper exists and who it’s for.

Listening to readers has always been at the heart of Eugene Weekly. This year, that meant launching our popular weekly Activist Alert column, after many of you told us there was no single, reliable place to find information about rallies, meetings and ways to get involved. You asked. We responded.

We’ve also continued to deepen the coverage that sets Eugene Weekly apart, including our in-depth reporting on local real estate development through Bricks & Mortar — digging into what’s being built, who’s behind it and how those decisions shape our community.

And, of course, we’ve continued to bring you the stories and features many of you depend on: investigations and local government reporting, arts and culture coverage, sudoku and crossword puzzles, Savage Love, and our extensive community events calendar. We feature award-winning stories by University of Oregon student reporters getting real world journalism experience. All free. In print and online.

None of this happens by accident. It happens because readers step up and say: this matters.

As we head into a new year, please consider supporting Eugene Weekly if you’re able. Every dollar helps keep us digging, questioning, celebrating — and yes, occasionally annoying exactly the right people. We consider that a public service.

Thank you for standing with us!

Publisher

Eugene Weekly

P.S. If you’d like to talk about supporting EW, I’d love to hear from you!

jody@eugeneweekly.com

(541) 484-0519