When I was 17 years old, I lied about my age to get my first full-time job — as an orderly making $1.30 an hour at a state mental hospital where you had to be 18 to get hired.

“What’s your Selective Service status?” asked the head nurse, an affable but no-nonsense guy with gray hair, who wanted to make sure I wouldn’t be drafted and sent to Vietnam the moment he put me to work.

“4-F,” I said, ad libbing. “Heart murmur.” I realized too late it might not be wise to offer a fake medical excuse to a registered nurse.

“What caused it?”

I began to flounder. “Rheumatic fever?” He looked doubtful. “Look,” I finally said. “I’m 17. But I really need this job.”

Turned out he really needed an orderly. “You can start work tomorrow. Just don’t tell anyone how old you are.”

That was my introduction to South Carolina State Hospital, the second oldest state mental institution in the nation. The hospital was and still is known by locals as Bull Street, for the road that fronted its 181-acre campus in downtown Columbia. Founded as the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum in 1821 as part of a Quaker-led reform movement in mental health care, it consisted of a dozen or so stately old red brick buildings with white columns, surrounded by bucolic green lawns and fragrant magnolia trees. Today Bull Street — along with many state mental hospitals around the country — is shut down, leaving many of the nation’s severely mentally ill untreated.

Some people would like to bring elements of the old system back, along with reforms. State mental hospitals had flaws, but they took care of thousands of people, says Lisa Dailey, executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit founded in Arlington, Virginia, in 1997 to change civil commitment laws so that people with severe mental illness can again be forced into medical treatment.

Enlarge

In a telephone interview, Dailey says the state hospital system worked well in the early 20th century at providing a safe place for people with mental illness to get help. What caused that system to fracture, she says, was two-fold: It was called on to care for too many incurable patients, such as those with dementia, and it was increasingly underfunded.

I applied for work at Bull Street because I needed a job, but also because I was fascinated by the romantic notion — elaborated in such then-trendy books as R.D. Laing’s 1967 The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise — that what society called “insanity” was a reasonable and creative reaction to a world out of control. I liked that idea, and I wanted to meet crazy, creative people.

My first shift started at 7 o’clock the next morning at a run-down brick dormitory that was part of a dismal unit called Remotivation II. There I found myself in sole charge of about 50 elderly men suffering from chronic and at the time untreatable schizophrenia. Dressed in worn out tan jumpsuits, they watched TV, smoked cigarettes, held incoherent conversations with themselves and batted away imaginary attackers.

My main job was to herd them, four at a time, into the shower room, where I’d get them undressed, hand each a bar of soap and then spray them down with warm water from a garden hose. Many were incontinent and required scrubbing. Some masturbated while washing; a few asked me to take part. If I worked fast enough I could hose down about half the population of the ward, get them dried off and into clean overalls during an eight-hour shift, keeping the ammonia stench in the ward down to just about bearable levels.

After a week I was back in the head nurse’s office. “I can’t do this anymore,” I said. “Is there any other job at the hospital that I can do?”

He looked sympathetic. “I’ve got an opening in the admitting unit,” he said. “You’ll find it more interesting. Just one condition. Get a haircut, and shave off that beard.” I hit the barbershop the moment I got off work that afternoon.

Enlarge

The men’s admitting ward was, by comparison, modern, bright and shiny. Upstairs in a wing of the neoclassical 1930s-vintage Williams Building, which housed the Admission-Exit unit, it had a series of semi-private rooms along a lengthy corridor, with the locked front door at one end and a comfortable day room, with tables and chairs, a television set and plenty of windows, next to a nurses’ station and a dormitory at the other.

Running things day-to-day on the ward was a senior orderly by the name of Dewey Grubbs, a big, commanding but easygoing fellow with the soul of a maternal master sergeant. Grubbs, who knew all 50 or so patients by name, pointed a few out for me to get acquainted with right off. “Talk to them in your free time,” he said. “Get to know them. There are some good people here.”

In the coming days and weeks I would learn how to hand out medication (always watch to see that a patient swallows the medicine and is not hoarding pills), how to host family members on a visit (imagine that they are your own parents), and how to approach a patient having a potentially violent breakdown (always put Grubbs in front). I showed up for work each day in a freshly starched and ironed white uniform that made me look like a junior Dr. Kildare.

Under South Carolina law in those days, anyone admitted to the state hospital was required to be held for 28 to 30 days of observation. The observation took place on our ward, and no one went home before a month was up and the physician in charge of their case said they were sane.

In 1969, the year I worked there, Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest was seven years old; the movie starring Jack Nicholson hadn’t yet been made. Both tell the story of the wild and charming Randle McMurphy, his friend the supposed-deaf-mute Indigenous Chief Bromden, and their battles with the brittle Nurse Ratched at an Oregon mental hospital that could have been an exact institutional copy of Bull Street.

Kesey’s book fed into the R.D. Laing romance about insanity — and would eventually help conservatives justify shutting the whole system down.

I found no sign of creative, romantic insanity amid the noise and occasional chaos of the Williams Building, but I did see a lot of care.

One night I was called down to the admitting room, where police — then, as now, the first responders to people in crisis — had just brought in a smelly, incoherent middle-aged drunk. As he lay on an examination table I helped remove his foul clothing and watched as a nurse cleaned up his left eye socket, which was missing the eyeball but full of greenish pus. Once he was scrubbed and given clean pajamas he spent a couple days in the medical unit until the docs decided he was healthy enough to join our ward. Within a week I learned he was a professional accountant, a man with a decent education, a middle-class family and a terrific drinking problem. Within a month he was helping us run the ward, while he and his doctor tried to figure out how he could navigate being released back to a world full of alcohol.

One day about midsummer, I was told to report the next evening for my shift to a ward in the Cooper Building, down the hill; I’d be taking the place of the evening orderly for a week while he was on vacation. It housed patients who, while not having been convicted of any crime, were uncooperative, disoriented or violent. Unlike the cheerful admission ward where I was now comfortably working, the Cooper Building was built with prison architecture. It had heavy locks and iron bars, and a wire cage surrounded the nurses’ station. This was terrifying news for a 17 year old who weighed in at about 125 pounds soaking wet. I’d be mostly on my own for eight hours each night.

The first evening a humorless nurse introduced herself, gave me a few tasks — including suicide watch on several patients held in isolation cells that looked like animal cages — and said she’d be back later as she made her rounds.

After she left, I sat down and started talking with a big African American man of about 30 who was locked in the closest cell. “I don’t really know what I’m doing here,” I said.

“Neither do I,” he said.

He made an interesting offer. He had a show he wanted to watch on TV that evening. If I would let him out to watch his show, he promised not only not to cause trouble, but that he would help me with any patients who did. “And I’ll tell you when the nurse is coming on her rounds, so you can lock me up again.”

Our arrangement worked perfectly. He got out of jail to watch TV every evening that week, and I had an entertaining assistant. There was never any trouble on the ward, he always warned me in time to lock him back in his cage, and we never got caught. On my last night in the Cooper Building I asked him what he had done to get himself put in solitary in the first place.

“I goosed that nurse,” he said.

Enlarge

Though I didn’t know it at the time, Bull Street was already in the process of being shut down. Using civil liberties as an excuse, conservatives around the country who didn’t want to spend money to help the mentally ill were seeing to it that South Carolina State Hospital and dozens of others like it were closed, and their patients released. In the early 1980s President Ronald Reagan began to finish the old hospitals off, promising a system of community care that never materialized. When I worked there in 1969, Bull Street had more than 6,000 patients; the last were released in the early 1990s. The Oregon State Hospital, founded in 1862 as the Oregon State Insane Asylum, never closed completely but has been drastically reduced in size; while it once housed more than 3,500 patients, it now has beds for 620.

Yes, there were problems in the old hospitals. The worst abuses occurred as the system was collapsing when it was defunded. At a Congressional hearing in 1985, South Carolina state Sen. Arthur Ravenel Jr. testified that on a visit to the hospital in 1983 he personally saw that “Youths ranging in age from 12 to 16 years old had been stripped naked, strapped face down in four-point restraints to the floor, and some had been heavily drugged to lessen their struggles and mute their cries.”

But those were aberrations — nearly all brought on by severe understaffing as a result of grinding budget cuts — in a much larger historical picture of competence and care. When I worked at Bull Street, straitjackets and shock therapy were relics of the past, and for every Nurse Ratched there was a Dewey Grubbs.

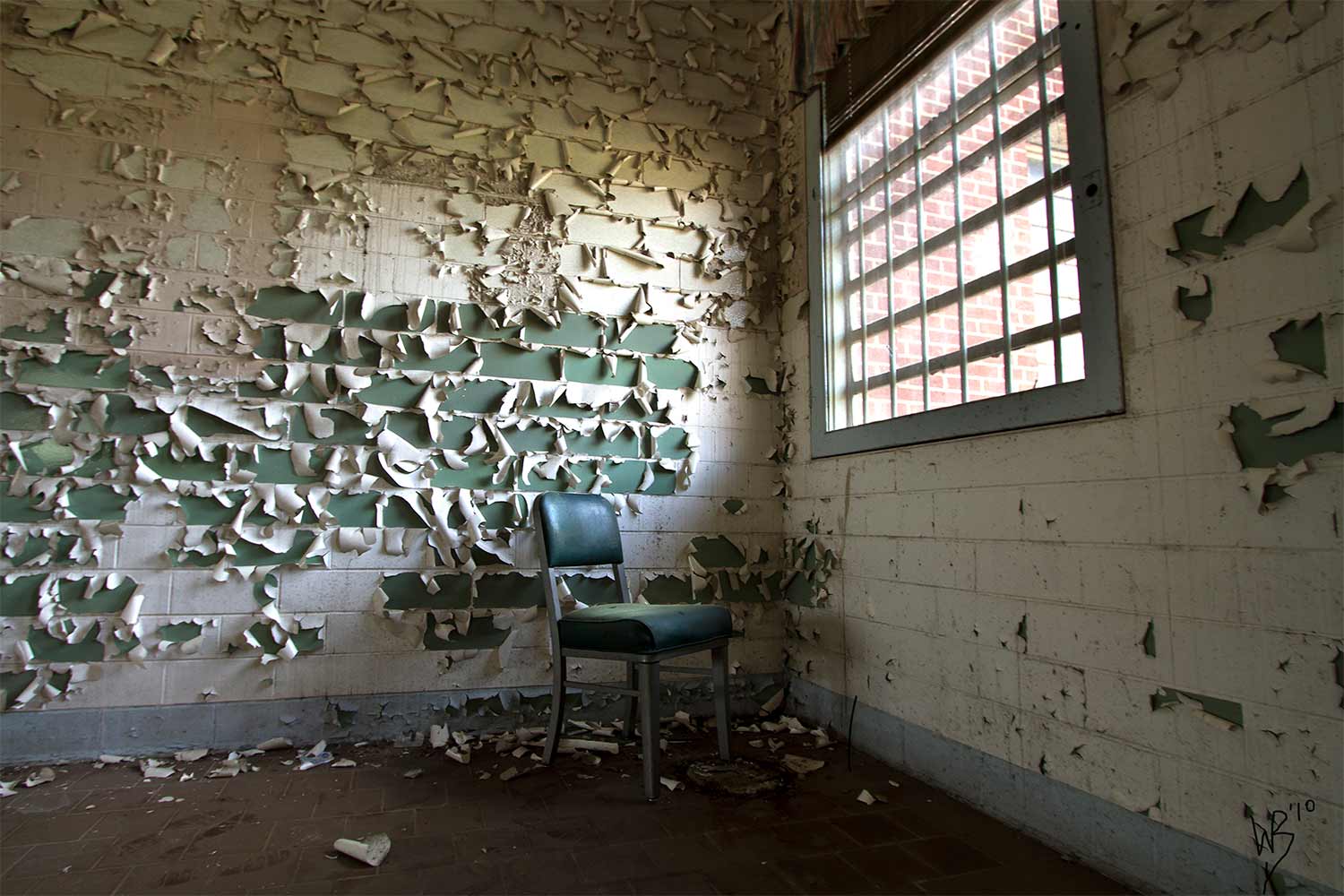

For decades after its patients were gone, Bull Street was nothing but a haunting ruin. Its stately buildings, one of them on the National Register of Historic Places, sat abandoned and decaying, attracting teenage drinking parties by night and ruin-porn photographers by day.

As a prime piece of real estate in downtown Columbia, Bull Street has now been sold to developers and fully gentrified as the BullStreet District. Where once stood a hospital that was revolutionary in its founding, there’s now an REI store, luxury condos starting at $500,000, a minor league baseball field and upscale restaurants, including a barbecue place in the old hospital morgue.

In his 2020 book The South Carolina State Hospital: Stories From Bull Street, South Carolina newspaperman and photographer William Buchheit gives accounts from 24 people who worked at Bull Street. One of those former employees written about in the book was Bill Fort, who worked as an orderly in another male ward in the Williams Building the same year I was there.

Now 72, as I will be in July, Fort was then 17 and also lied about his age to get his job, though he was smart enough not to get caught. He’s retired from a career as an employment counselor with the South Carolina Employment Security Commission.

Enlarge

Fort and I both remember the care that was given to people who were so broken that they couldn’t begin to take care of themselves — people like some you still see today, Buchheit says, living on the street next to the posh BullStreet District.

“A lot of things are lost,” Fort says. “And especially the opportunity to help people, to help alcoholics and drug addicts. We need those facilities.”

He is especially angry about the depiction of mental hospitals in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “They tried to act like all the employees really hated the patients. They didn’t, and you know, who would want to? What profit would there be in doing harm to those people? It was just crazy. But that’s Hollywood.”

Civil commitment should be seen not simply as a legal decision, says Dailey of the Treatment Advocacy Center, but also as a medical one. Current antipsychotic medications can help people with schizophrenia live reasonably normal and productive lives, she says, but it can take months of treatment before a patient becomes stable enough to live on his or her own.

Delaying treatment for psychosis, she says, is harmful in itself. “What happens if you delay getting treatment to somebody who needs treatment is that their ability to recover gets further and further away because it actually causes brain damage,” she says.

When I look back on my days at Bull Street, I can’t help but think Dailey is right. Yes, there was abuse, and that cannot be allowed to happen again. But we need a mental health system that actually helps people suffering the most severe problems — that helps them even, sometimes, against their will — rather than relegating them, as we do now, to prisons, jails and living on the street. That is the real abuse.