In the early ’70s Jerry Rust did what any ambitious hippie with long hair to match would do: co-found a tree planting co-op called Hoedads. The people of the Hoedads Reforestation Cooperative were real hippies. They slept in vans, shared meals together, grew their hair out and worked for nobody but themselves.

“Their problems become your problems,” Rust says. “When you work together you thrive together.”

Rust says he started Hoedads after returning home from a stint in the Peace Corps in India. He had successfully dodged the draft, met a woman who would become his wife, had a couple of kids, and realized very quickly that he needed to make money. Rust found tree planting to be “surprisingly” lucrative.

“I wanted to start a company where everyone made money, not just the company,” Rust says. “So we started a co-op.”

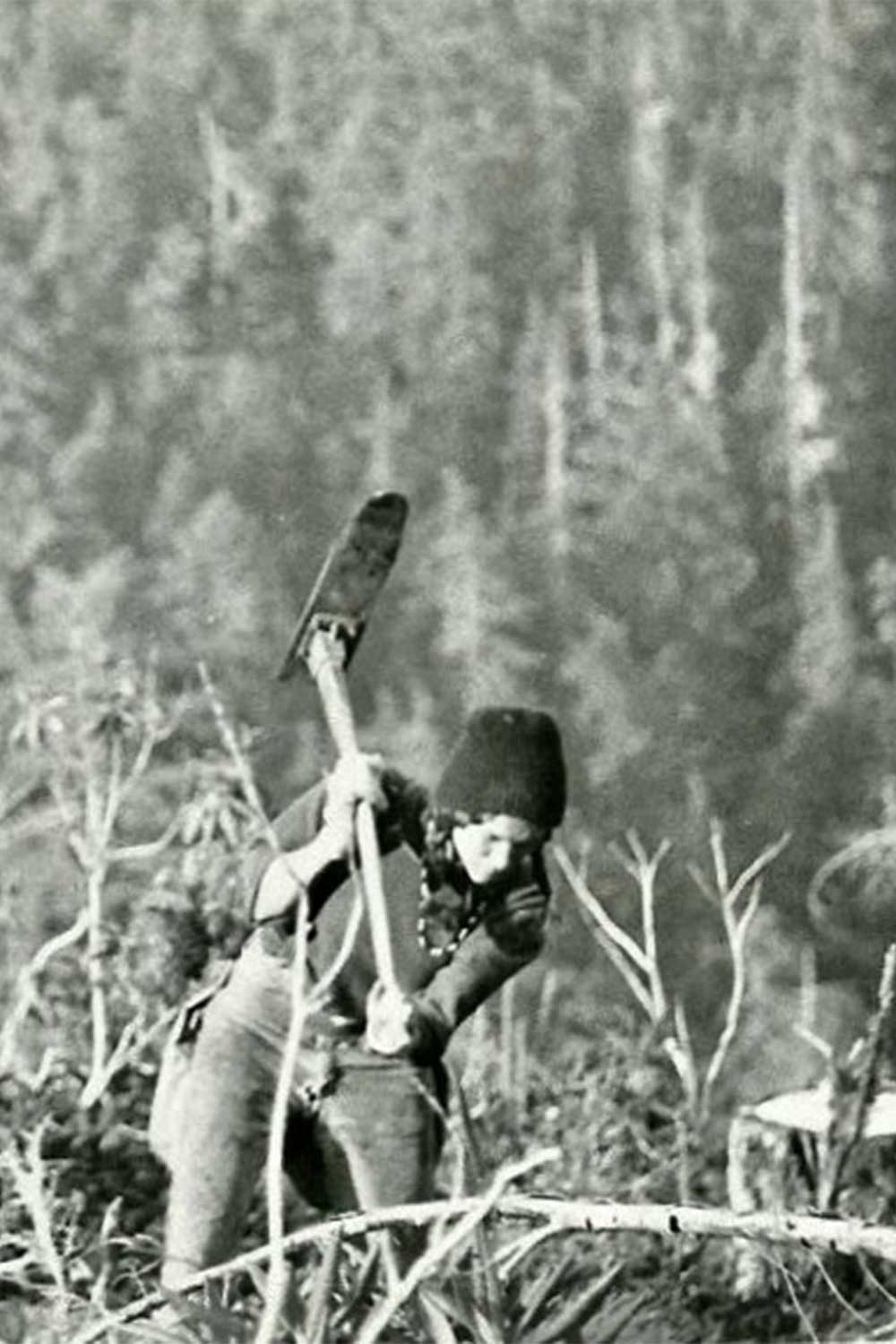

After the timber industry devastated Oregon’s forests by clearcutting trees in the first half of the 20th century, tree planting became a vital job in restoring forests. Rust and his friends, Hoedads co-founders John Sundquist and John Corbin, bid on a Bureau of Land Management contract for planting 63 acres on the Oregon coast during the winter of 1971. Planting trees is not for the faint of heart. It’s usually done in Oregon’s cold, wet winters and consists of digging a hole in the ground with a hoedad, tossing a seedling tree in and moving on to the next one.

“You had to be hardy,” former Hoedad Francis Eatherington says. “Everyone expected you to be hardy and not complain.” Their first winter was wet and profits were low, but with each season came more contracts.

The Hoedads, named after the long metal shovel used to plant trees, grew from a small company to more of a counterculture movement. Hoedads was one of the first workplaces in Eugene to include women and Latinos; it had all-women crews and all-Latino crews. Former Hoedad Greg Nagle says they were apathetic to conventional society. “We had educated people, but we also had working class, and we had people who did drugs and people who didn’t and veterans and Latinos,” Nagle says. “Mostly, we were pissed off about the war.”

Nagle was a key member of Hoedads from 1973 to 1987, writing newsletters for the cooperative and working in the forest until he decided to take his knowledge about forestry and put it towards a degree. He got his undergrad degree and Ph.D. at Cornell University in forest and watershed science and ended up working as a scholar-in-residence at the university, giving lectures in the forest and watershed sciences departments, and was paid to do research. He now continues a career in research in Vietnam, where he has lived for nearly 12 years.

At its peak, in the late 1970s, the Hoedads consisted of about a dozen or so crews with 10 to 12 people in each, and raked in nearly $6 million per year. Their influence seeped into Eugene’s politics for decades to come. The Hoedads were a major fundraising help in saving WOW Hall (aka Woodmen of the World Hall) from being sold in 1975. Most notably, Rust was a left-leaning voice in Eugene politics as Lane County commissioner for 20 years, fighting for forests and the environment, often as the lone liberal on the commission.

“Jerry Rust would not have been county commissioner if it weren’t for the Hoedads and the hundreds of Hoedad volunteers who worked on his campaign,” says Roscoe Caron, who was Hoedads president in 1982.

One of the things that stuck out to Caron more than anything was that in Hoedads, “every voice mattered.” Despite the fact that there were sometimes 200 to 300 people at Hoedads meetings, he says, when people stood up to speak they were listened to. “You had to have the confidence that what you have to say is of value, and so I learned to stand up when I speak.”

Caron says he has taken that skill with him throughout his career as an activist, professor and his favorite role, middle school teacher.

Hoedads stunned suited-up contract inspectors with their cooperative leadership and messy hair, which Rust says was always a delight. They challenged the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to put an end to corrupt tree planting practices such as hiding or burying seedlings instead of planting them.

“Hoedads had a huge influence on the anti-herbicide/pesticide movement,” says former Hoedad Cece Headley. “There was a lot to be proud of.”

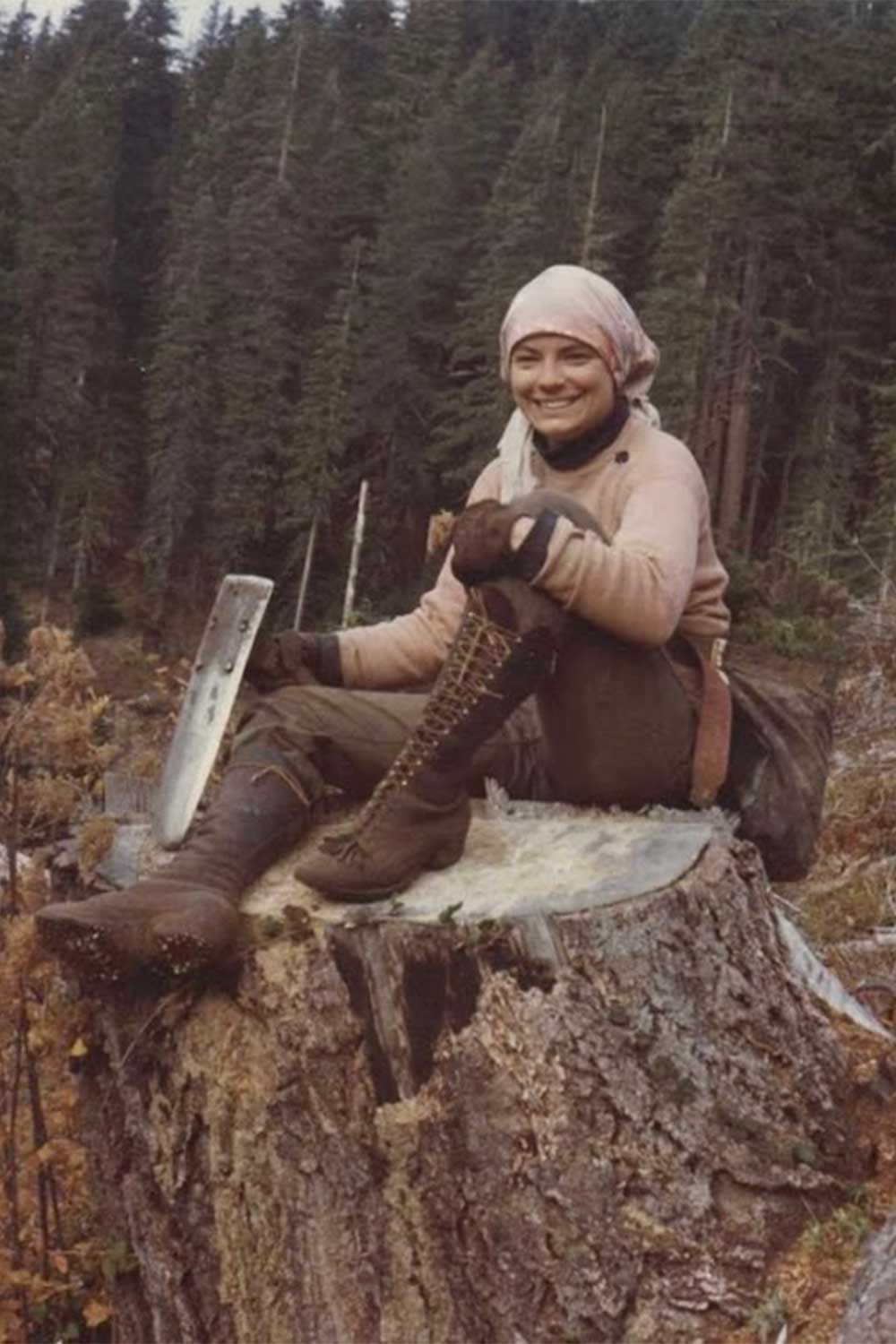

She was one of the dozens of women who worked in the Hoedads cooperative through the years. Twenty-eight-year-old Headley was not what she says is your typical Hoedads woman. She was married already had a three-year-old child by the time she came across the Hoedads. Headley was a part of a few different crews during her time as a Hoedad, including the Cheap Thrills and Flying crews. Each crew democratically named themselves and were free to run their operation however they pleased as long as it was done without a boss. Headley was also a part of a select group of people who planted trees in Alaska every year.

She looks back on her time in Alaska fondly, despite having almost died her first trip when she took the wrong boat and despite the persistent men in the remote bars.

“One of the gals in our Alaska group was blonde, and she would say that we’d be out in the bush for weeks and we stank and she would go to a local bar and still get marriage proposals,” she says while chuckling. “Alaska was a great time. Just great memories.”

Headley ended up leaving Hoedads in 1992 to help raise her kids, but came back to the forest as her own contractor in the late ’90s.

“I can never say how grateful I am to the organization. I learned everything from Hoedads,” she says. “I learned how to work in the forest; how to bid; how to negotiate a contract; how to work with the government; how to run a business.”

Headley worked as a one-woman show; planting the trees and doing her books up until she retired.

Hoedads didn’t just plant trees. Eatherington’s favorite part about Hoedads was measuring the trees by climbing them. “I mean, I was the only person in the world to ever go in that spot; 160 feet off the ground up in that tree,” she says. “We got to see the whole world around us. I mean, it was just out of this world.”

Before Eatherington was a tree climber she was a cultural anthropologist at the Douglas County Museum.After a friend pointed her to Hoedads, she was hooked on forestry.

“I remember just being stunned by the size of the trees laying on the ground that we had to climb over,” she says.

Eatherington loves her motorcycle almost as much as she loves trees. In the early ’80s she zipped through forests on a dirt bike, climbed trees and made heads turn at local bars when she and the rest of her crew of tree planters walked in.

“It was sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll,” she says.

Eatherington was a part of Half and Half, one of two women-only Hoedads crews, Full Moon Rising being its predecessor. Known for being a primarily lesbian crew, Half and Half got its name for the way their crew split their profits. Half a worker’s share was based on how many trees each individual planted and the other half of the profits were divided equally among the women.

“Hoedads changed a lot for us. We learned how to work together and be a cooperative,” Eatherington says. “I would say Hoedads probably changed the world.”

Eatherington went on to work for nonprofits, Cascadia Wildlands and Umpqua Watersheds, where she critiqued government logging proposals through the National Environmental Protection Act’s public comments process by going out into the forest and ground truthing the government’s claims. If the process didn’t work to save the forest habitat, she worked with lawyers to sue and stop the timber sales. Eatherington fought timber sale proposals at the Umpqua National Forest, the Coos Bay BLM, the Roseburg BLM, among others, and at the state level at the Elliott State Forest until retiring in 2016.

“I can’t imagine spending my life doing anything else,” Eatherington says. “I’ve lived in the woods since 1975. It’s my life.”

The Hoedads Eugene Weekly spoke with all had varying ideas of how this generation can make a difference in the forest. Rust sees carbon sequestration, which is the process of capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide, as the future whereas Headley believes young people should get involved through wildland firefighting. Eatherington would encourage any young person interested in forestry to work for a nonprofit like Umpqua Watersheds. But what every Hoedad had in common was the belief that another organization as unifying and impactful as Hoedads could be a saving grace for the young people of today.

If anything, Hoedads are more than ready to pass on the torch to a generation crippled with the ticking time bomb of climate change. “When I die, dig my grave with a silver hoedad and hope I grow into something good,” Rust says.

This story has been updated to reflect that CeCe Headley was referring to the Half and Half crew when she says she was one of the few women who wasn’t a lesbian, not the Hoedads as a whole.