When Matthew Dickman was a sophomore in high school, like many of us did at that age, he had a crush who he wanted to impress.

His crush loved poetry, so Dickman thought that maybe if he started writing “really bad versions of other people’s poems to put in her locker,” he might have half a chance to go out with her, he said.

While these romantic gestures were unsuccessful, they laid the foundation for Dickman’s lifelong love affair with poetry.

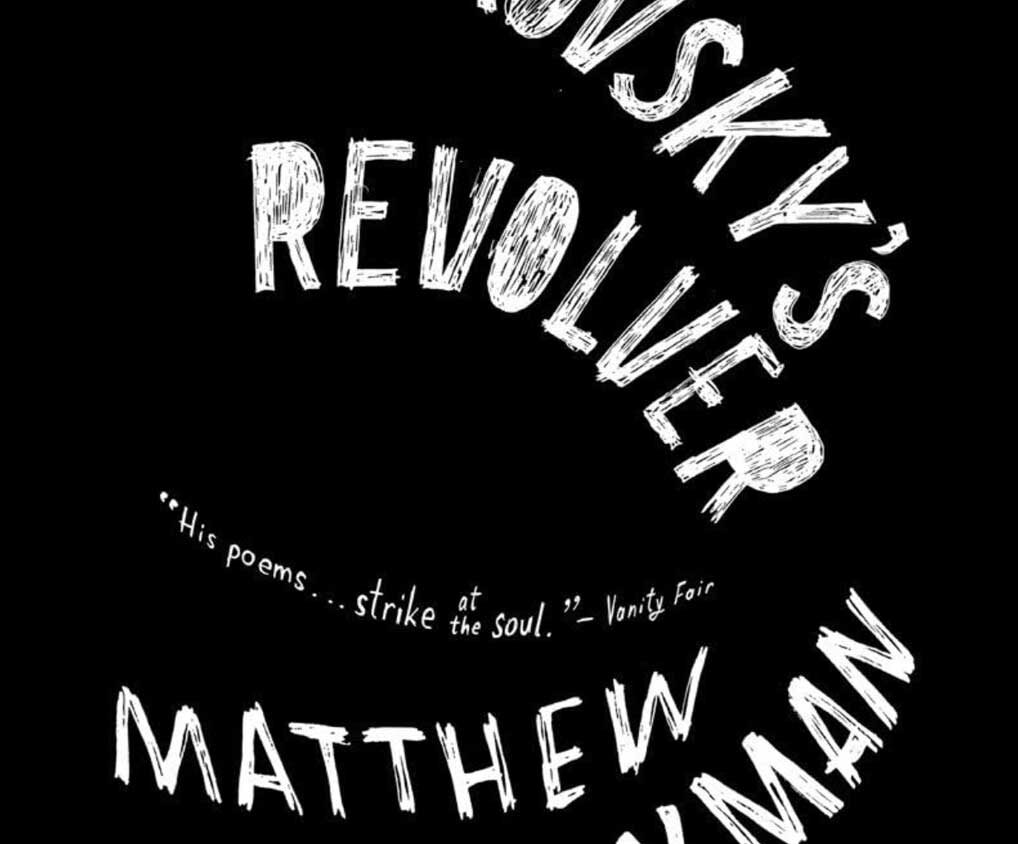

Looking back more than 30 years later, Dickman has written four full-length poetry collections. His first book, All-American Poem, won the 2008 American Poetry Review First Book Prize in Poetry and the 2009 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. A First Book Prize judge described Dickman’s work as “spiritual in character — free and easy and unselfconscious.”

In a full-length interview, Dickman opened up about his childhood and how it influenced his poetry, his role in a Steven Spielberg film, serving pizzas at Whole Foods to support his writing career and his eventual return to teach at his alma mater, the University of Oregon.

Dickman’s poetry is rooted in his upbringing. He and his siblings were raised by their single mother, Wendy Dickman, in the Lents neighborhood of Southeast Portland.

“It was an impoverished neighborhood,” he tells Eugene Weekly. “There was a lot of drug addiction and alcoholism. A lot of absent dads, or if the dads were around, they were violent. Often, the moms were violent. And there was a kind of contract passed down from fathers about what it meant to be a guy, and one of those things was you certainly don’t fucking talk about your emotions.

“There weren’t fathers around who were asking you, ‘How do you feel?’ And for me, I think poetry was that parent.”

Now, Dickman himself is a parent, and he still uses poetry as a means of navigating complicated family dynamics. His most recent book, Husbandry, released in 2022, details his own journey as a single father.

In general, the arts have provided solace for Dickman. He and his identical twin brother, Michael Dickman, who is also a poet, did theater together in high school. They dreamed of becoming actors before they pursued their writing careers, and even signed with an agent, which ended up affording them quite the opportunity.

A few years had gone by with no roles to speak of. Then, one day, Dickman’s mom received a phone call from a Los Angeles casting agent who wanted him and his brother to audition for a Steven Spielberg film called The Minority Report.

The Dickman brothers got the parts as the precognitive twins, and, in thanks, they gifted Spielberg a first-edition book by the poet Nelly Sachs, which he ended up using as a prop in the film’s final shot.

When the Dickman brothers saw the film and Sachs’ face on the back of the book, Dickman says they celebrated, saying, “Fuck yeah, awesome! We got Nelly Sachs in a sci-fi Hollywood film!”

After The Minority Report and graduate school at the University of Texas, Austin, Dickman returned home to Portland and worked at Whole Foods while continuing to write poetry.

Following the critical acclaim of Dickman’s first book, All-American Poet, he and his twin brother were profiled in The New Yorker. They thought that after this profile was published, their writing was going to take off.

But soon after, while he was working at the pizza island and finishing his closing duties at Whole Foods, his apron covered in flour, Dickman noticed the man who would come in to replace the store’s magazines and newspapers.

One of the new magazines that night was The New Yorker with the profile on him and his brother. As soon as the man was done replacing the magazines, Dickman says the man “just walked over to me and he was like, ‘Do you have any leftovers?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, let me box up a couple things.’ Then, I looked at the magazine stand, and I just thought, ‘Fuck. Nothing’s gonna change.’”

Though, for Dickman, writing poetry was never about being successful or winning praise.

Just like it had been throughout his life, poetry was there for him in times of love, but also in times of grief, like when his older brother, Darin, died by suicide.

“When I was writing in my second book a lot about my older brother’s death, or in my most recent book when I was writing a lot about the separation between me and my children’s mom and being a single dad, they’re tough subjects. But there is also always a joy in the act of creating, whatever it is.

“For me, it’s never been therapeutic in a classic sense, but it has helped me understand my life.”

Dickman has also worked as a freelance copywriter and written several Super Bowl commercials, all while continuing to write poetry.

Now, Dickman lives in Portland and teaches as a visiting professor in the creative writing program at the University of Oregon.

Geri Doran, a fellow University of Oregon creative writing professor, tells EW via email, “It’s terrific to have Matthew teaching with us this year in creative writing. His poems hold his readers in thrall: they’re full of energy, wit, tender intimacies, and human devastations — all cast with an observant eye and a big heart.”

Yet, even after a successful career filled with awards and praise, Dickman is most proud of something else.

“I would not say that I’m a great poet. I would not say I’m a great boyfriend. I would not say that I’m a great anything. I make a pretty good pie crust, and I’m a pretty good baker. But the thing I’m most proud of is being a father.”