By Emma J Nelson, Brianna Murschel, Amelia Winkelman and Ellie Graham

Oregon legislators are preparing to dismantle the voter-approved reform of how the state deals with drug addiction.

Bills taking shape in Salem would once again make it a crime to possess small amounts of heroin, methamphetamines and other hard drugs. Oregonians decriminalized drug possession in 2020 when they approved Measure 110 with 58 percent of the vote.

The measure’s backers argued more treatment, not jail time, was a better prescription for people addicted to opioids.

Since then, Oregon has been swamped by an unprecedented opioid crisis. The state saw 280 opioid overdose deaths in 2019, according to the Oregon Health Authority. Three years later, the toll hit 956. The numbers aren’t in for 2023, but the trend shows the state was headed to break another record.

Politicians now blame Measure 110 for the rising rates of overdose deaths. In January, Rep. Rick Lewis, a Republican from Silverton, captured the conventional wisdom in Salem when they blamed the reforms for the current crisis.

“The citizens of Oregon understand the failures of Measure 110,” Lewis said in a statement. “We see the results on the streets, in the unacceptable overdose death rate, and in the catastrophic consequences to our communities, to public safety and to livability.”

But there’s a side to the story most Oregonians aren’t hearing: Data-driven research suggests Measure 110 isn’t the culprit and that doing away with low-level drug possession laws neither unleashed the crisis nor made it demonstrably worse.

On Jan. 22, RTI International, a North Carolina-based research institute, hosted an all-day symposium in Salem to examine Measure 110’s effects on Oregon. RTI’s work is funded by Arnold Ventures, a Houston-based foundation that has championed Measure 110 and other drug-reform law efforts. (An Arnold Ventures affiliate, for example, gave $700,000 to Drug Policy Action, a national advocacy group, to support Measure 110’s passage.)

The symposium brought in a wide array of voices — 16 speakers from research centers including the University of Southern California, the University of Michigan and Brown University. The panelists also included experts who focus their work on harm-reduction policies.

A single day’s presentation of the leading research can’t by itself unpack the complexities of Oregon’s overdose crisis. However, the symposium’s highlights offer a sense of balance to the current debate over Measure 110’s future.

Overdoses in Oregon were already on the rise before Measure 110 passed.

One clear message from the symposium: Overdoses in Oregon were already on the rise before Measure 110 passed.

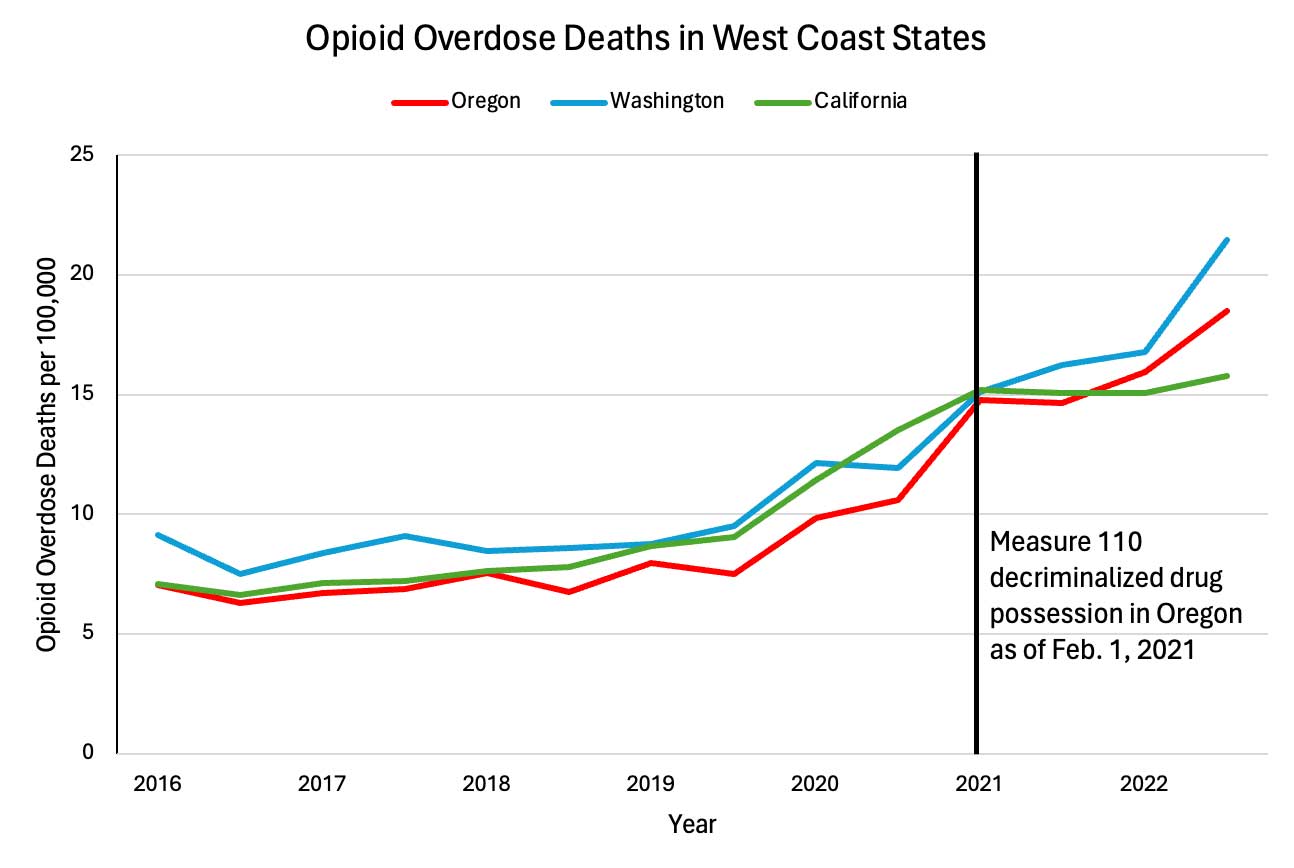

Presenters at the symposium noted that the increase in opioid overdoses that Oregon is seeing today started in 2019. By 2020, the year voters passed Measure 110, the death rate for opioid overdoses had already increased by one-third from only five years earlier.

They also noted street-level fentanyl was already taking hold in Oregon.

Fentanyl is a powerful opioid often used by physicians to treat severe pain. Its tiny grains are 50 times more potent than heroin, and that puts users at far greater risk of overdose, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Illegal drugs containing fentanyl can include pills produced in drug labs or mixed with other drugs, such as meth, cocaine and heroin. Researchers say many people who overdose have no idea that fentanyl is present in the drugs they’re taking.

“It is possible for someone to take a pill without knowing it contains fentanyl,” the Drug Enforcement Administration reports. “It is also possible to take a pill knowing it contains fentanyl, but with no way of knowing if it contains a lethal dose.”

The fentanyl wave slammed into Oregon just as Measure 110 took effect.

Starting in 2014, fentanyl as a street drug swept across the U.S. from east to west, with states such as Maryland and New Hampshire first witnessing fentanyl playing a significant role in overdose deaths.

Researchers can track fentanyl’s impact with federal data that indicate which opioids were linked to overdoses. The data show it took five years before the wave reached the Midwest and Western states such as Oregon.

In 2016, data from the RTI symposium show, fewer than one out of 40 overdoses in Oregon involved fentanyl. The most recent data show fentanyl now plays a role in nearly half of all overdoses.

So when was the fentanyl tipping point in Oregon?

Brandon del Pozo, a former police officer turned Brown University professor and researcher, told the symposium that the data show Oregon experienced its first “fentanyl supply shock” in the first three months of 2021 — right as Measure 110 went into effect.

“Fentanyl is not only the apex predator of people who use drugs,” del Pozo says, “it’s the apex predator of confounding variables and drug policy.”

Researchers also argued that Measure 110 did not make Oregon’s overdose rate worse than it would have been otherwise.

Oregon is the only state to have decriminalized drug possession. If Measure 110 affected overdose death rates, Oregon’s opioid death rates would look significantly different than other states that still made drug possession a crime.

But that’s not the case, according to three studies presented at the symposium.

In September 2023, Spruha Joshi, assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan, and six co-authors published a study that used the experiences in 48 other states to predict how Oregon’s overdose rates would have turned out if the state had not passed Measure 110. The study, which appeared in a Journal of the American Medical Association publication, then compared Oregon’s actual opioid overdose death rates.

“We see no difference in sort of what would have happened in Oregon if Measure 110 had not been in place,” Joshi told the symposium.

Joshi noted the published study covered only one year after Measure 110 passed, but that she has continued to track data since then, and her conclusions have stayed the same.

Alex H. Kral, an epidemiologist and RTI International researcher, told the symposium his research examined how Oregon’s overdose rates compared to its neighboring states, which experienced the impact of fentanyl arriving around the same time.

“If it was just Measure 110 in some way, you would see Oregon look very different than the rest of those states,” Kral said. “Oregon’s looking just like its neighbors, so it can’t be Measure 110 that’s responsible for this one way or the other.”

Del Pozo’s research comparing Oregon to other states reached the same conclusion. Oregon, del Pozo added, is “surprisingly mundane when it comes to the ability of fentanyl to interfere with drug policy and take human lives.”

Del Pozo said his research suggests that recriminalizing drug possession will not lower overdose rates.

Washington law made possession of heroin and other drugs a felony until February 2021, when the state supreme court struck down the law as unconstitutional. The court ruling left Washington with no law against drug possession for about four months until the Washington Legislature passed a new law again making possession a crime.

Washington’s overdose rate didn’t drop when drug possession was made a crime again. Del Pozo said just the opposite happened.

“Fentanyl was still tightening its grip on Washington, and overdoses were on an inexorable rise,” del Pozo writes in an email. “Decriminalization and recriminalization weren’t going to stop that, and recriminalization certainly didn’t slow it down, either.”

The researchers noted the limitations common to all such studies. In many cases, their data extended only through 2022. They also say that it’s too soon to see any effects of the increased drug treatment services promised under Measure 110.

Much of the funding for treatment programs didn’t go out from the state until mid-2022, and panelists say they lack the data to see whether those programs have had any impact on overdose rates.

The symposium received scant news media attention, but some news outlets have noted the research. The Salem Statesman Journal, KGW-TV in Portland and Portland newspaper Street Roots focused reporting on people experiencing homelessness. Oregon Capital Chronicle and Willamette Week have also reported on RTI research in the past. On Feb. 8, The Lund Report, a news site that covers Oregon’s health policy, provided an analysis and critique of the research presented at the symposium.

This week, Kral tells Eugene Weekly that he doesn’t know if the research made public at the symposium has had any effect on the debate over Measure 110.

“We want legislators and the general population of Oregon to understand and know research findings with respect to M110,” Kral writes in an email. “When comparing to neighboring states, the data are clear that M110 has not been responsible for any changes in overdose deaths or crime.”

He adds, “It is too early for us to know whether M110 is meeting its intended goals. Fifty years of drug criminalization doesn’t get reversed in three years.”