On display at Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art until August 25 is a relatively small but powerful show, comprising 10 works, titled My Body, My Choice? Art and Reproductive Justice. Judy Chicago’s serigraphs envision the moment of birthing, Nao Bustamante’s series centers on gynecological care, and Alison Saar’s larger-than-life depictions of African American women were made in response to the 2022 decision by the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Chicago’s famous work “The Dinner Party” (1974-79), now permanently on display at the Brooklyn Museum, set the table for significant women from history and is a landmark in feminist art. Her art in My Body My Choice? is from another large-scale project, the “Birth Project” (1980-1985).

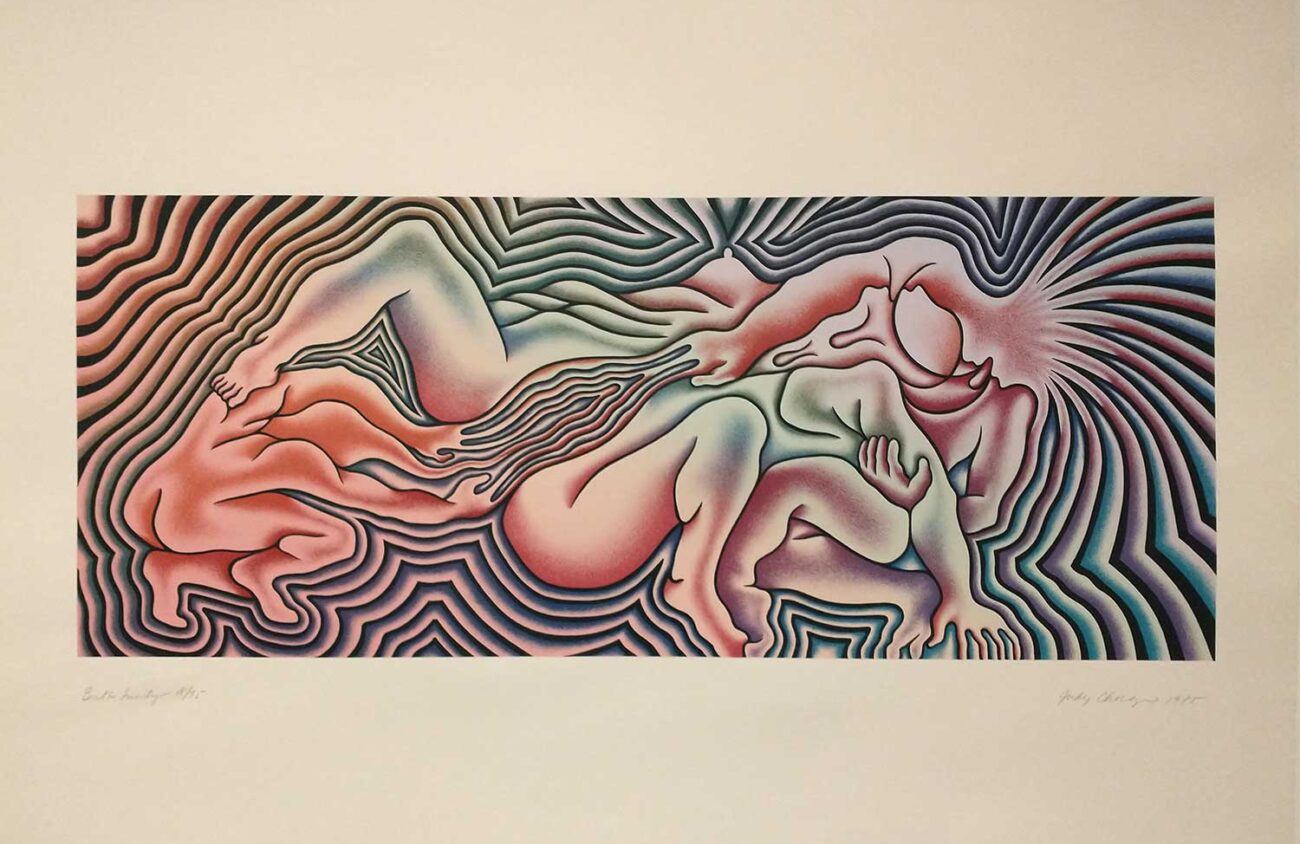

For five years she collected information from hundreds of women about their reproductive experiences, their creative fiber art images of pregnancy and childbirth, and made drawings and prints of her own. Her print “Earth Birth” is dark, perhaps set at night. The woman at the center is on her own, and the land around echoes the shape of her body. “Birth Trinity” is a blast of psychedelic colors and vibrating lines that depict a woman giving birth, accompanied by someone helping. Her vagina, the focus of the image, is a strange, graphic, but beautiful cartoon-like vision of creation.

Los Angeles-based artist Saar’s art primarily focuses on the African diaspora. Hers two works — “Plucked” and “Uproot” — are monumentally sized at 108 inches tall, but they seem delicate in contrast to Chicago’s linear figures. Painted on vintage cotton picking bags, the two African American women represented are more realistically drawn, even when surrealistically combined with branches of the cotton plant.

Inspired by historical accounts of slaves ingesting plants to induce their own abortions, one woman is shown with the roots of a cotton tree in her mouth. The heavy subject matter is contrasted by the lightness of the presentation. The figures hang on cotton fabric that you can easily imagine outside on a clothesline being blown by the wind.

Bustamante’s contribution is a series of five multi-media works called “Bloom Speculum Suite” and a video titled “Gruesome History.” Both focus on the speculum, an instrument used by gynecologists during pelvic exams.

The suite reimagines the speculum designed after the forms of flowers. It’s composed of five lovely images juxtaposing colorful flowers with illustrations of speculums yet to be made.

“Gruesome History,” in stark contrast, is a video narrated by a talking speculum. The speculum teaches us about the awful origins of gynecology — which includes performing experimental operations on slave women. It is a disturbing piece of art, and not perhaps in the way the artist intended. Rather than reflecting on the horrible past, I found myself wondering why I was learning about it from a funny-sounding hand puppet.

One couple noted, “The puppeteer seemed to be using a kind of Donald Duck voice.” Another woman with gray hair chuckled on her way out, “I’m glad I don’t have to go through that again.” And then clarified she meant the speculum, not the video.

She could have been referring to either because if she had stayed then she would have heard the history over… and over. The video is replayed about every four minutes, and it provides the background sound for viewing the entire exhibit.

If I could make a suggestion, it would be to have headsets for listening to “Gruesome History,” giving visitors a choice for how they wanted to experience the rest of the art.

The exhibit is a companion show, a visual counterpart to the Common Reading Program at the University of Oregon. That program distributes a different book every year campus-wide to faculty in a multitude of disciplines. This year’s common reading, by Diana Greene Foster, is The Turnaway Study: Ten Years, A Thousand Women, and the Consequences of Having — or Being Denied — an Abortion.

My Body, My Choice? Art and Reproductive Justice isn’t meant to illustrate the book, but rather respond creatively to the subject matter. Each artist interprets the theme differently while at the same time reflecting a singular message: put decisions about women’s health into the hands of women.