“People have been painting icons in Russia for at least 1,000 years,” says Russian-born artist Olga Volchkova in a 2016 “Oregon Art Beat” profile. She paints them, too, but with one exception — her icons are not Russian angels or deities, but rather saints of her own invention.

Inspired by her adopted country, the artist uses the techniques of her ancestors to express gratitude and admiration or perhaps even worship the natural landscape in Oregon, where she now lives.

Florae Animalia, a group show at Karin Clarke Gallery running until June 22, features art by Volchkova, as well as Claire Burbridge, Matthew Dennison and Marjorie Taylor. The title of the exhibit is taken from Volchkova’s series of works, and it sets the tone for the atmosphere in the gallery: a realistic approach of representation with a supernatural twist.

Personifying nature is Volchkova’s forte, and among the plants she deifies is the bearberry shrub. “St. Bearberry” features a portrait of a bear and a girl in a field of berries. A blurb beside the painting informs us that, according to Anishinaabe (an indigenous group in the Great Lakes region) legend, “Bear put a berry” into a baby’s mouth, ensuring that people would not starve.

The title, Florae Animalia, carries with it a reference to scientific classification, and Taylor, whose “vegan taxidermy” is displayed throughout the gallery, was a social scientist before becoming an artist and is now emerita professor of psychology at the University of Oregon.

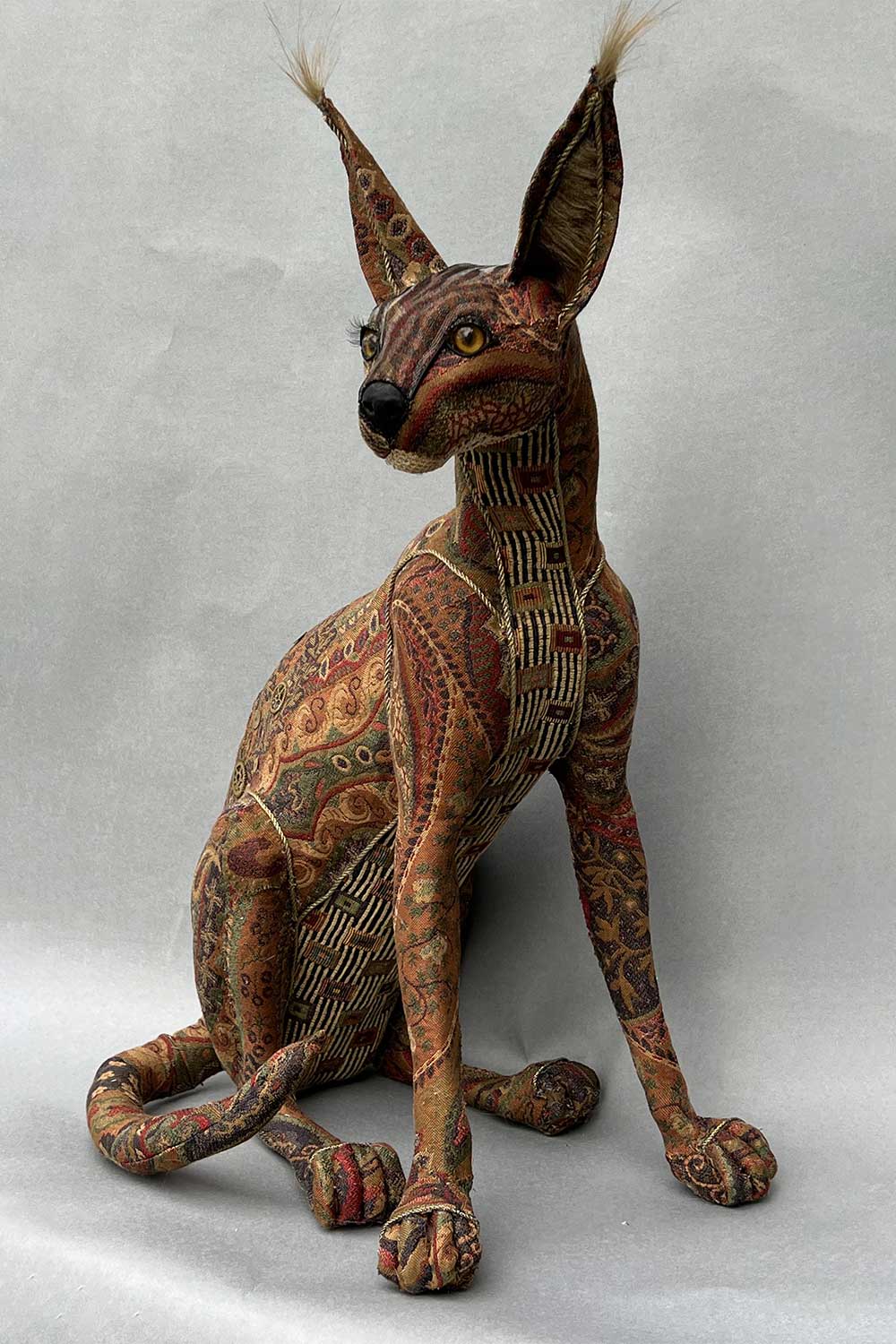

A self-taught artist who has worked with quilting, beads and wearable art, Taylor’s three-dimensional animals are well placed among the paintings by exhibit designer Tina Schrager, providing pause and contrast to the two-dimensional works in the show.

Taylor’s sculptures are both realistic and fantastic. She creates the form of an animal by wrapping wire with layers of paper mâché, replicating its actual size and shape, but then covers the armature with human-made fabrics. The result is a hybrid creature, a fox or cat that looks intensely familiar and has real presence but whose eyes peer out from behind multi-colored tapestries.

Burbridge takes you to the forest. Her drawings and paintings depict scenes you might encounter on a hike in Oregon but have elements that don’t quite belong. An unidentified feather or abstract form, possibly resembling a microscopic cell, might be floating among the trees. And much the way it would if you were on an actual hike, the sight of it stops you in your tracks.

Burbridge was raised in Scotland and studied art at Oxford University. She focused on printmaking and sculpture until she moved to Ashland, where she turned, or returned, to her first love — drawing. She works with graphite, colored pencils, ink and watercolor. Her meticulous attention to detail, whether depicting bark, lichen or abstract forms, is a mediation of nature.

“Forest Apparition” takes place at night. Working with white on a dark background, Burbridge uses her unique brand of pointillism so the dark spaces seem as alive as the trees.

Of the four artists in this group, Dennison’s portraits of animals are the most straightforward in terms of representational style, but even his subjects have a unique look about them. This is because he manipulates his oil paint without using a brush and instead paints with gloved hands, rags or paper.

I saw Florae Animalia during the day, but later that same night I saw something in nature I’d never seen before, and never thought I would, at least near Eugene — the Northern Lights. The sight of the Aurora Borealis, looking as if it was materializing out of nowhere, reminded me that it is possible to see something wonderful in a familiar spot, whether looking up at the sky or at a bearberry shrub in your own backyard.