One of the least known — but most influential — photographers ever to work in Oregon is the late Terry Toedtemeier. Trained as a scientist — he earned a bachelor’s degree in earth sciences at Oregon State University in 1969 — Toedtemeier picked up a camera instead of a test tube and became fascinated with photography during the wild and wooly artistic experimentation of the 1970s. He never looked back.

In 1975 he was one of the five founding members — along with Portland artist Chris Rauschenberg, son of the nationally known painter Robert Rauschenberg, and now-retired University of Oregon art professor Craig Hickman — of the cooperative Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, still a significant photography venue in the fine art world.

In the 1980s Toedtemeier taught as an associate professor of art and history at Pacific Northwest College of Art, and in 1985 he became the first curator of photography at the Portland Art Museum, a job he held until his sudden death in 2008.

That came one evening just moments after he gave a talk on a book he had co-authored with writer and editor John Laursen titled Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River Gorge, 1867-1957. Still in print from OSU Press, it is an illustrated study of historic photos by such influential early Northwestern photographers as Carleton Watkins, Fred Kizer and Ray Atkeson.

A small but compelling show of Toedtemeier’s own work opened in May and is on display at the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art through August 11. Terry Toedtemeier: Photographer comprises just 15 black and white silver gelatin prints, made by Toedtemeier himself. They come from a larger gift of Toedtemeier’s work to the museum 18 months ago by his widow, Prudence Roberts, former curator of American art at the Portland Art Museum.

Selected from that collection by Thom Sempere, the JSMA’s associate curator of photography, the exhibit is presented in chronological order. Its first five photos come from those wild ’70s days, beginning with a delightful cat photo (no, those weren’t actually invented by social media) and showing the exuberance of a talented, aspiring artist and his friends.

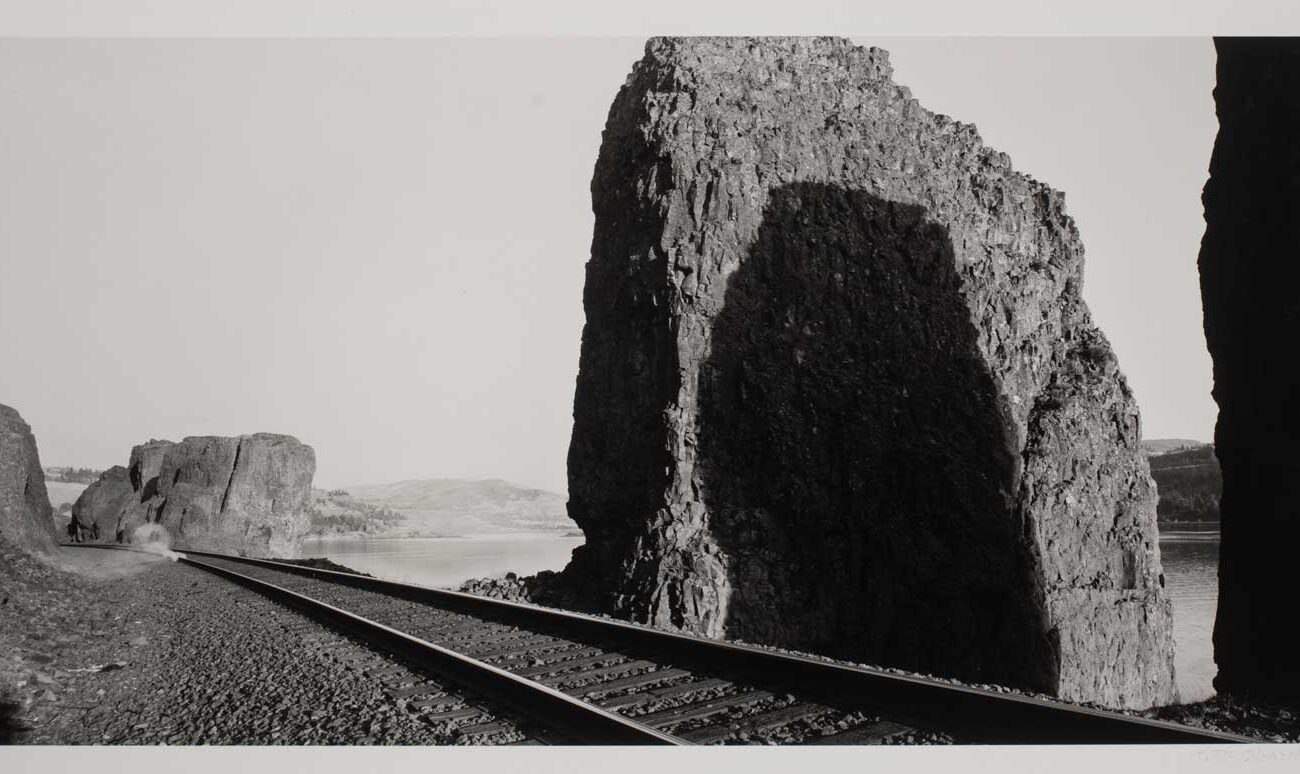

The 10 later photos in the exhibit unveil a landscape master at work. Toedtemeier grew up to become an artist and curator instead of a geologist, but he never lost his deep love for geology and its often beautiful abstract forms.

He photographed Oregon’s rocks and desert, ocean and sky, in a landscape he sometimes noted was entirely built on volcanic basalt. The show’s subjects include volcanic cones, coastal rock formations, a distant salt flat and even an old wooden log flume, all traditional icons of the Northwest landscape but seen, in his work, with fresh artistic eyes.

Add to that his exquisite black and white technique — you should look closely at these photographs to fully appreciate their intense beauty — and Toedtemeier easily earns himself a place in Northwest photographic history alongside the 19th century masters whose work he so earnestly admired.