One night in late 2016, Booker Bartow — best known in those days, if at all, as a skateboard videographer and hip-hop DJ performing as “Nomadic” — was skateboarding down a hill near his home in the Nye Beach neighborhood of Newport when he hit a patch of black ice.

When he came to on the cold pavement, the 30-year-old had a fractured skull, a broken clavicle, a dislocated shoulder and several smashed ribs. He was bleeding from cuts and scrapes all over his body, but especially his head. No one came to his aid. He crawled back to his house and passed out again when he got inside, bleeding all over the couch. Before losing consciousness he took a selfie and posted it on Instagram, leading his uncle, who happened to see it, to come over and take him to the hospital.

That, Bartow says, was a pivotal moment in his life, which had lately been mired in a haze of alcohol, drug use and anger over the death that year of his father, the renowned Oregon artist Rick Bartow, and the death of his mother years before.

As he’s telling me this story, Bartow and I are sitting in the cluttered, dark upstairs living room of the small Nye Beach house where he lived and took care of his father, whom he refers to as “Pops,” for several years after the senior Bartow suffered a debilitating stroke in 2013. The room is still packed with Pops’ possessions, including a line of guitars in black cases — Rick was a rock ’n’ roll musician on top of his art career — a large shelf full of art books and a framed portrait he made of Oregon artist Lillian Pitt. A weed pipe sits amid the mess on a coffee table, and on this bright spring day, the curtains are all drawn, giving the room the twilight atmosphere of a shuttered cave.

Though he’s 38 years old, Bartow looks two decades younger — tall and thin, almost emaciated, pale of skin with dark green eyes and short hair concealed by a baseball cap. He supports himself largely by eBaying thrift shop items he finds and sports cards from a lifetime collection. His only housemate these days is an elderly, talkative and highly opinionated cat named Tut, who loudly reminds him it’s lunchtime as we discuss life as the son of a nationally respected Native American artist.

It’s not always easy growing up in the shadow of a giant, and Rick Bartow was clearly a giant in the art world.

One of the elder Bartow’s immense carved wood sculptures — his 26-foot-tall “The Cedar Mill Pole” — was exhibited in the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden at the Clinton White House. Another, built from two large poles and titled “We Were Always Here,” is on permanent display outside the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

The elder Bartow’s drawings, prints and paintings are in collections around the West and around the country, from the Portland Art Museum and Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Oregon to the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, the Yale University Art Gallery and the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

In 2015, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon mounted a large retrospective titled Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain. After the exhibition here, the show toured to 10 other art museums around the West.

To hear Booker Bartow tell it, his childhood was idyllic, growing up on rural property his great grandfather, John Bartow, of Wiyot heritage, had homesteaded in the early 20th century in South Beach, a couple miles south of Newport, after walking there from Northern California in 1911. It was on that property that Bartow’s father made art in several ramshackle studios in outbuildings on the homestead, as his mother, Julie Swan, oversaw Booker’s home-schooled education. For a bright, inquisitive kid, this amounted to paradise, one that involved not only practicing art but experiencing nature at his doorstep.

“Mom was a basketmaker,” he says. “Dad was multi-media. They made sure I had my own set of tools.” A family photo shows 4-year-old Booker putting wood scraps together with his father to make masks. “I was free roaming. I chose what to make and which studio I was going to work in.”

Paradise was lost to Booker in 1999, when Swan died of breast cancer. “That was a jarring shift. She was my rock. She was the main structure for my home schooling. I was an odd nut, a unique kid. And she worked with me.”

After his mother’s death, Booker found himself enrolled, for the first time, in school. Showing up for eighth grade was a dizzying experience for a home schooled odd nut. “When I started going to public school I lost focus. I was drinking and smoking and losing my way.”

A sympathetic art teacher helped, and Booker made it through to graduation, leaving town soon after he had his diploma, and moving to Eugene. Here he buried himself in the Washington Jefferson skateboard community. He got into hip hop, performing at house concerts and the rougher edge of Eugene area pubs.

He had a hard time fitting into mainstream culture. “The lifestyle I grew up in, I didn’t know how alternative it was,” he says. Skateboarding, with its sheer physicality, fed his strong desire to stand out.

By the time he had the accident, Bartow had begun to cut back his drinking, to take control of his life. “But I was still carrying the baggage,” he says. “That wreck was a further stepping stone.”

His story of the skateboard wreck echoes one that was often told by his father, who had come home from military service in Vietnam as a 21-year-old with a serious drug and alcohol addiction fueled by the guilt, anger and trauma of his main job in the Army — playing rock ’n’ roll guitar in field hospital concerts to entertain horribly wounded young men who had endured the combat he never saw first hand. That job earned him a Bronze Star for service, a medal that, in his bitterness, he threw away.

Rick Bartow used to say he didn’t clean up his act until one night, in an alcoholic furor, he started a fight with the wrong young tough and woke up on the street in Newport, battered, bruised and with broken teeth.

In the end it was art that saved him, the elder Bartow often said. “I drew myself straight.”

Booker Bartow started drawing himself straight soon after the skateboard accident. “That was pivotal for me, a moment of clarity and focus.” But it wasn’t until last year when Eugene gallerist Karin Clarke mounted a new show of his father’s work that he became fully serious about art.

“That show sparked a fire in me,” the young Bartow says. “She put together a collection of small etchings and large drawings. There was something for everyone. It took me back to being a kid working from studio to studio — and that freedom of being a kid.”

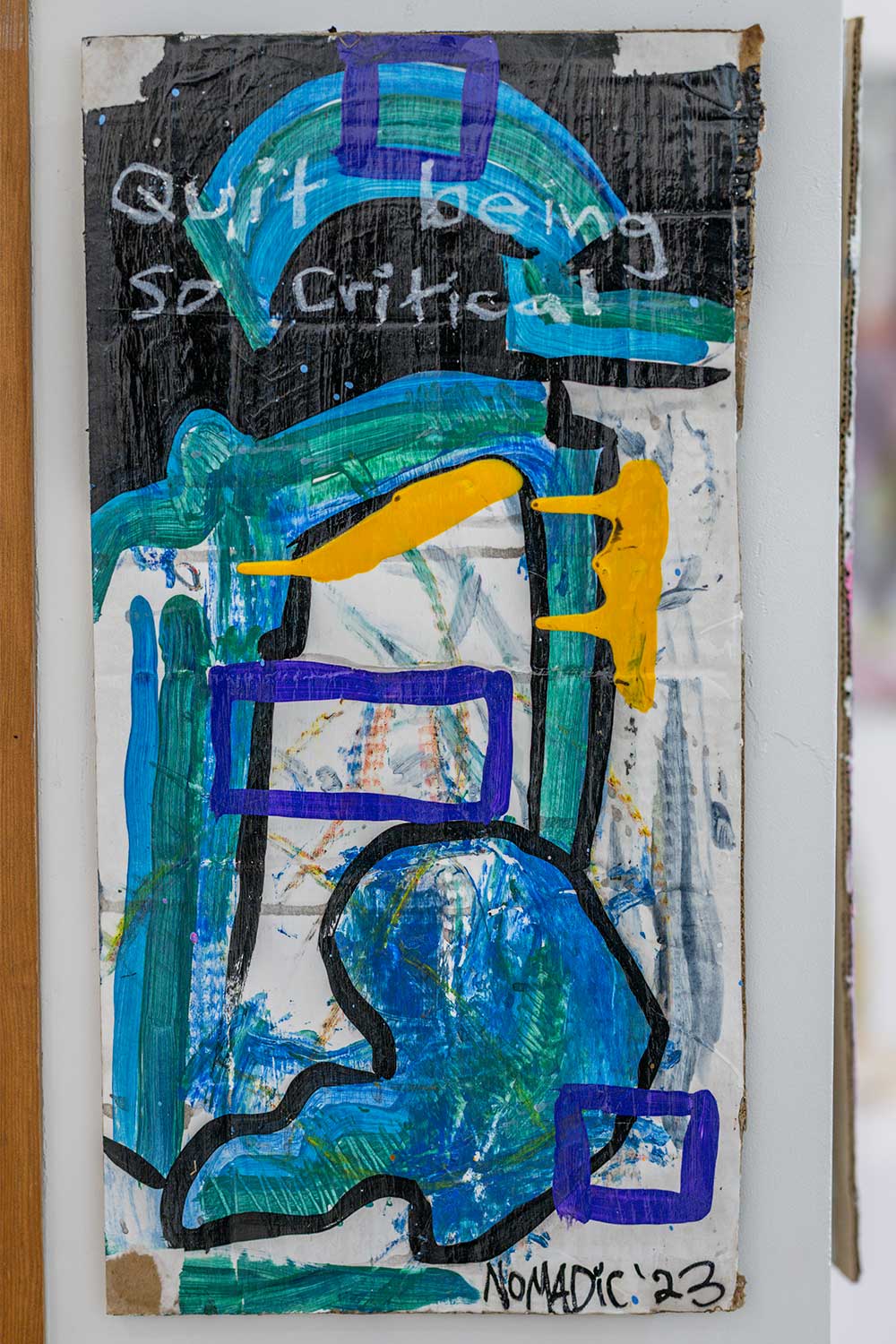

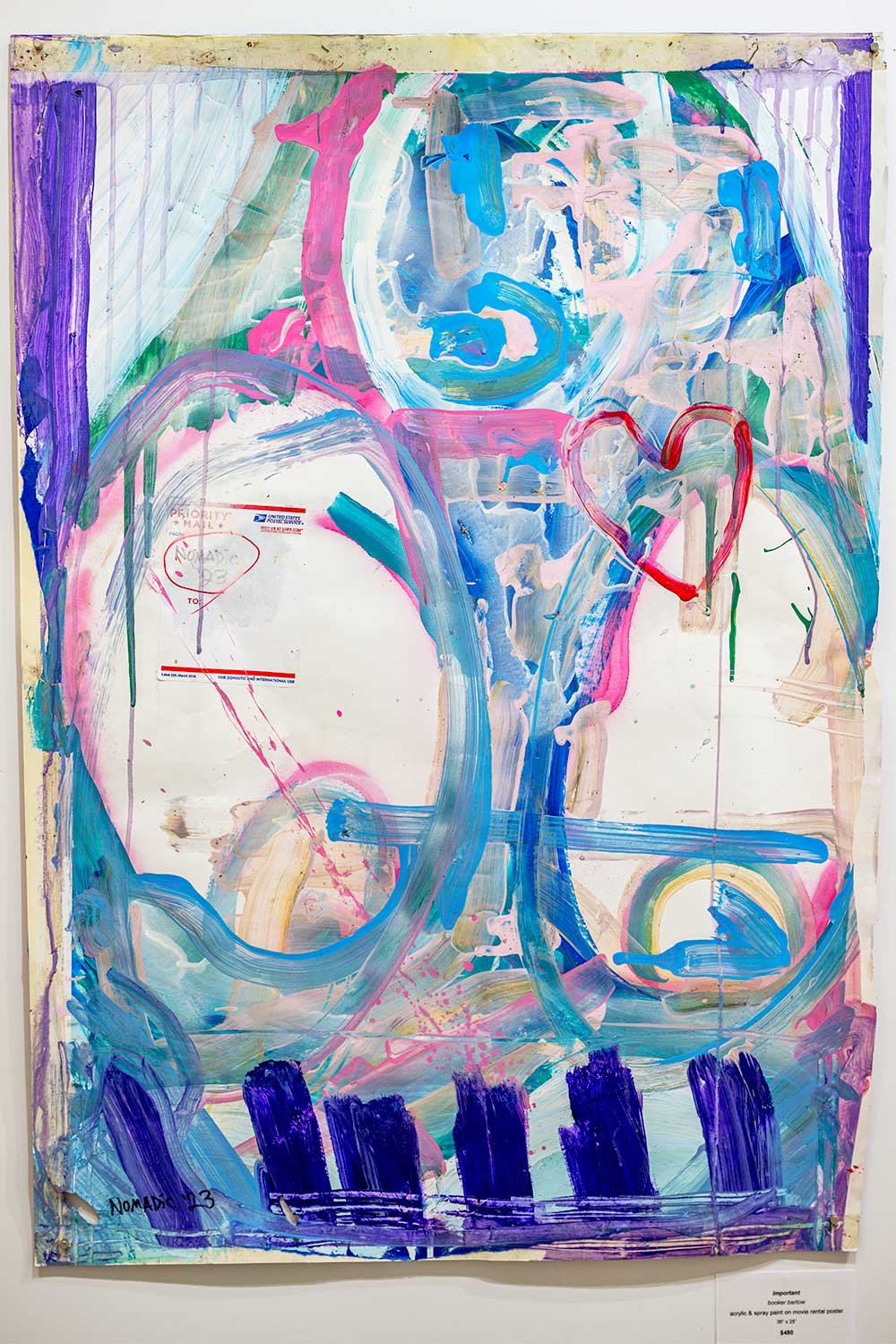

Often rising at dawn, he now works each day painting, drawing and making prints in a cramped outdoor studio he’s fabricated on the back porch of his house. With little money to spend on art supplies, he uses whatever is available. Where other printmaking artists create their work using carved wood or linoleum panels, Booker carves images to print from on salvaged sheets of Styrofoam. He paints on any surface that comes to hand — corrugated cardboard from recycling bins, old newspapers, even thrift shop fabrics.

That inner fire, fueled by hours in the makeshift studio, resulted in his being included in a summer show of painting by local Indigenous artists that runs through July 28 at the Newport Visual Arts Center, just around the corner from Bartow’s house.

As we walk through the upscale ocean view neighborhood to the nearby arts center, we talk about Nye Beach’s history as a center for artists and writers. No more, he says, pointing out that virtually every house on his street is now being rented on Airbnb. No one actually lives in any of them full time. “It’s all been gentrified,” he says, and there is no more artsy community.

At the arts center the staff welcomes him cordially and points us upstairs to the section where his work has been hung under the title “South Beach Salamander,” a reference to Bartow’s childhood obsession with catching salamanders near his South Beach childhood home. Though he’s already seen his work on display several times, Bartow’s eyes light up as we come up the stairs to the wing where it’s now on display in a space that could pass for a small upscale gallery in Chelsea, from the bright white walls to the unusual art mediums that Bartow combines in his work.

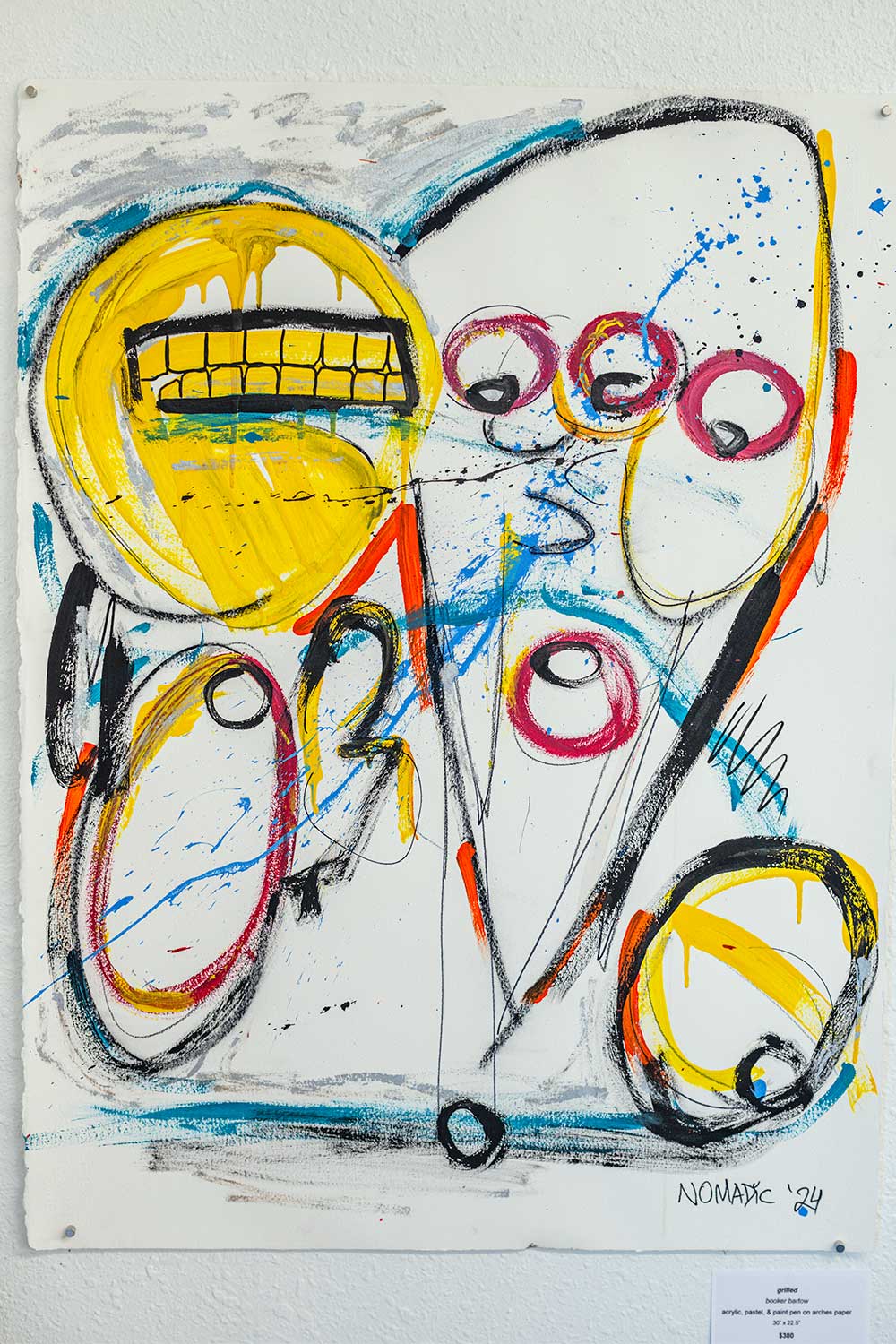

The gallery tag for “No Saint,” a large painting on fabric, lists as its medium “acrylic, pastel, paint pen, pipe resin, safety pins, plastic beads & charcoal on vintage rainier sleeping bag.”

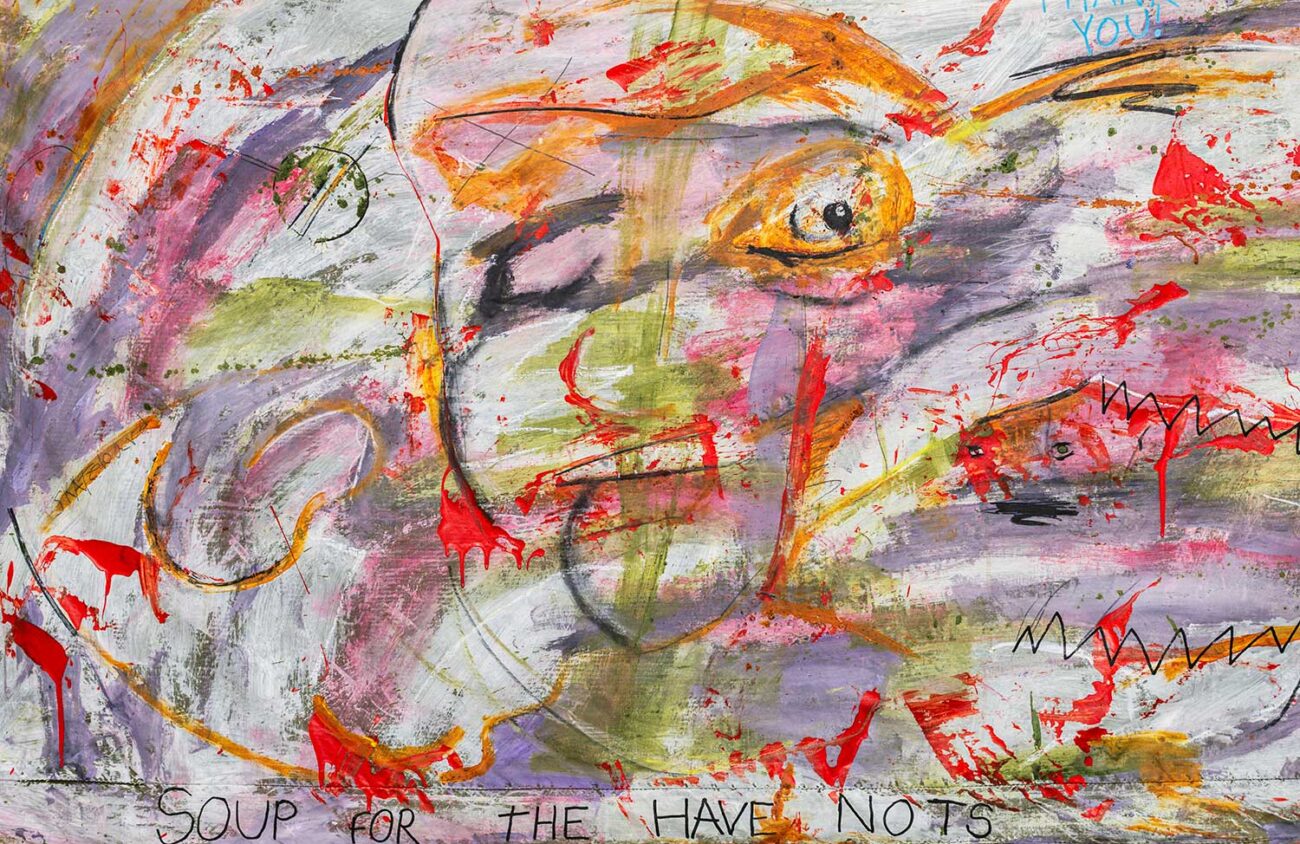

His paintings and prints, rarely done from observation, grow out of imagination and churning emotions, with occasional text woven into the art to offer a hint for the viewer. The large sleeping bag painting, which otherwise consists of chaotic abstraction, includes the words “no pain, no gain, no saint.”

Similar to his father’s work, if perhaps not as sophisticated, Bartow’s paintings in the show — signed “Nomadic” — are often built around startled or anguished faces, sometimes focusing on the eyes, which are the only features in the image that are fully articulated.

He was invited to show his work earlier this year when the Arts Center put together Where Waters Meet, which also features work by Leonard Harmon, Leland Butler, Isabella Saavedra and Chantele Rilatos — all emerging artists with Indigenous backgrounds.

For Bartow, this is his first time showing his art in a venue more elaborate than a café. “I didn’t know what to expect,” he says. “The whole thing is very surreal. The reception had good attendance, and I got a lot of positive feedback. I’m just taking it as it is.”

He hasn’t completely turned his back on his previous life, though he’s tried to defuse the anger he once felt. He still signs his work “Nomadic,” the name which he used in his skateboarding and hip-hop days. And he hasn’t turned his back on skateboarding, even if it nearly killed him. “I still skateboard,” he says. “But it’s much more about the breeze in my face now.”