By Martha Freeman

Twenty years ago, my book The Trouble with Babies was removed from a school at the request of a trustee horrified that the parents of a kid character were identified as gay.

As far as I know, none of my other books has been challenged, but the issue remains important to me as an author, a parent, a grandparent and a citizen. That’s why this year I joined Authors Against Book Bans (AABB), an organization founded to uphold the freedom to read. This month, AABB, the American Library Association and many other groups mark Banned Books Week (Sept. 22-28) to highlight and celebrate the value of free and open access to information.

Trouble was banned in Pennsylvania. Now I live in Oregon, widely thought of as progressive. In fact, Buzzy Nielsen of the State Library of Oregon’s Intellectual Freedom Clearinghouse notes that the state constitution has stronger free speech protections than does the U.S. Constitution.

But even here, an historically high 93 library titles were challenged in 2022-23. (The state library will release 2024 data later this month.) Today, Nielsen believes the clearinghouse’s work tracking attempts to restrict access to books and library materials is more important than ever “as libraries in Oregon and across the country face record challenges that disproportionately impact BIPOC, 2SLGBTQIA+, people with disabilities, and others whose voices are most often silenced.”

The sad fate this spring of legislation to prohibit schools and libraries’ restricting access also signals the need for vigilance. In February, State Sen. Lew Frederick of Portland, a former teacher, introduced Senate Bill 1583 which would have prohibited book bans based on race, gender identity, country of origin, sexual orientation, disability and immigrant status.

The bill attracted written testimony from some 500 people, more than any other bill during the session, with comments split about evenly pro and con. The senate passed the bill but — rather than bringing it to the floor for consideration — House leadership effectively killed it by adjourning the legislative session early. A legislative aide to Frederick says they learned a lot from the experience and hope to reintroduce a version based on their superior knowledge.

Alan Gratz, a bestselling author, recent transplant to Portland and AABB co-founder, notes that mustering people to fight book banning may be “even harder in a progressive state, where people think, ‘It couldn’t happen here.’ But it is happening here!”

In fact, it is happening right now in Tillamook where the school board voted to remove Julia Alvarez’s 1991 classic, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, from the 10th-grade honors English syllabus. Wondering why, parent Nikki Brown read the book and now spearheads the effort — supported by the Tillamook County Pioneer newspaper — to have it reinstated.

Alvarez immigrated to the U.S. from the Dominican Republic, fleeing a repressive regime. Her regard for democracy is echoed by 25-year Oregon resident and AABB member Jennie Englund, who believes that censorship represents “the most dangerous freedom we can revoke; it’s our very first amendment. If we tweak that one, what happens to the rest of the Constitution?”

As Englund suggests, book challenges pose threats beyond discrimination. In Tillamook, for example, the challenge to Garcia Girls arose because a student was uncomfortable with a scene in which a would-be predator takes advantage of a teenager. Yes, the scene is creepy! And it’s an opportunity for readers to consider and potentially defend against such behavior.

Also, as Heather Sears, Eugene Public Library youth services supervisor, notes, parents have a responsibility when it comes to choosing what young people read or don’t. For parents to exercise that responsibility, libraries, schools and the public need to make available what she calls “a wide scope of materials to meet the needs of various viewpoints and ages.” In Tillamook, the teacher had offered options to Garcia Girls.

Years after The Trouble with Babies was banned, a graduate student’s research identified it as the first mainstream book for the age group with gay characters. I hadn’t written it to break new ground, only to represent the world I knew, which included gay parents. Alvarez has said she started writing because she did not see the world she knew represented in books when she was a child.

One reason for books is to represent the world in a way that helps readers understand it and themselves. If books are going to do their job, we the people — authors, teachers, librarians, readers, families and citizens — must fight to keep them accessible.

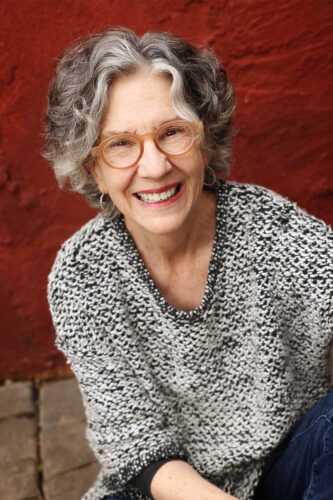

Eugene resident Martha Freeman is a member of the Oregon chapter of Authors Against Book Bans and the author of 35 books for children. Write to her at martha@marthafreeman.com. For more on Authors Against Book Bans, go to AuthorsAgainstBookBans.com.