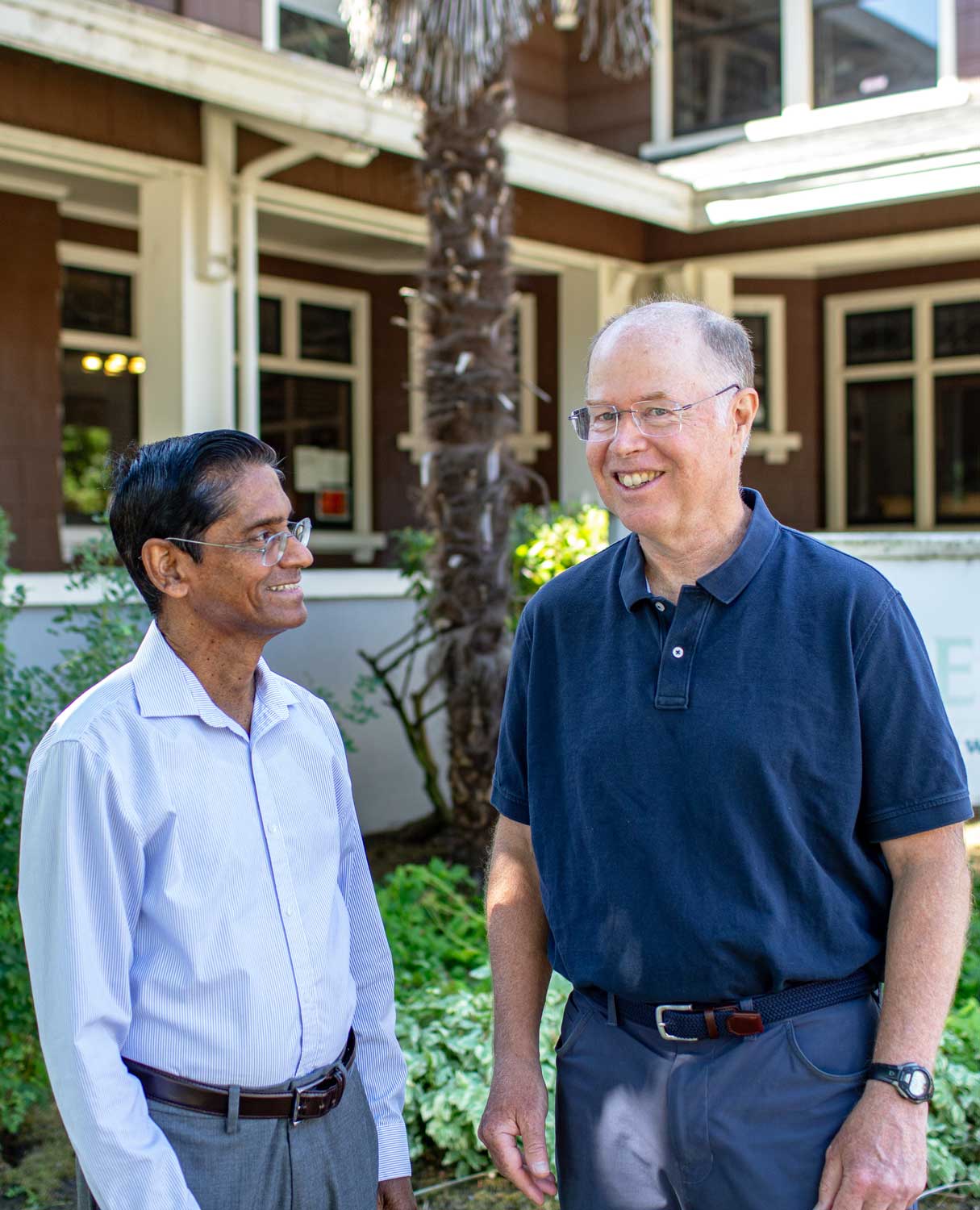

The Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide is known globally for its efforts on the intertwined issues of human rights and the environment in over 80 countries. After 33 years as the ELAW executive director, Bern Johnson announced his retirement in June. With a new executive director, Lalanath de Silva, the nonprofit with 30 employees around the globe and an office in Eugene continues to look to its future.

ELAW makes a worldwide impact with its work supporting community efforts to challenge unsustainable development projects that threaten wildlife and ecosystems.

The nonprofit focuses on creating and strengthening laws to provide better protection for the present and future of our planet. ELAW does this by engaging and collaborating with attorneys, scientists and other advocates. ELAW’s impact begins when it receives environmental claims from citizens or organizations, looking for support or expertise in environmental law, scientific resources and human rights violations. ELAW focuses on correcting human rights violations caused by environmental damages across the world.

Projects take all different forms. For example, ELAW and its partners are currently helping launch a coalition to defend land and Indigenous and environmental defenders like Mexican attorney Eduardo Mosqueda Sanchez, who was held for almost a year on false charges after representing an Indigenous community challenging an illegal mining operation. The effort, called ALLIED — Alliance for Land, Indigenous and Environmental Defenders — brings together local, national and international organizations as well as individual defenders to fight the accelerating attacks on those seeking to protect the environment around the globe.

In August, ELAW announced a victory in a May 2021 maritime disaster. The MV X-Press Pearl cargo ship caught fire off the coast of Sri Lanka. According to an ELAW report, “Twelve days later, it sank causing one of the worst ever maritime disasters.” The incident spilled more than 1,680 metric tons of plastic pellets, affecting communities and wildlife like dolphins, turtles and fish.

ELAW partners are taking on the plastic pollution crisis and opening conversations with the United Nations to adopt a global treaty to rein in plastic waste.

The Center for Environmental Justice, a nonprofit organization in Sri Lanka focusing on improving environmental rights, called upon ELAW’s network for scientific support, examples of damages in other marine disasters and more. Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court ordered the Singaporean shipping company and involved parties to pay $1 billion for the environmental damage.

Over his tenure at ELAW, Johnson fought for lawyers around the world protecting human rights and the environment. ELAW’s work includes “defending the defenders” against threats and attacks — sometimes by the ELAW partners’ own government. Johnson’s goal has been to empower people globally and build a sustainable environment for future generations.

He was inspired in his youth to make an environmental impact. “My mother asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up,” Johnson says. ”I told her I wanted to be a dam buster, because building a dam and killing free flowing rivers is wrong.”

Growing up in Eugene, Johnson fostered a relationship with the environment around him while hiking, fishing and being surrounded by old growth trees, cold rivers and the Cascade mountains. As he got older, his growing interest combined with scientific perspectives and legal training generated a compelling case for him to spend his life protecting the environment.

“We need to do a better job protecting our planet,” he says.

After becoming its first staff attorney in 1991, Johnson spent 34 years at ELAW, eventually becoming the executive director. Now, at the age of 65 Johnson passes the torch to de Silva.

“It was a joy to work with ELAW and help build something special,” Johnson says. “You can look at your children and say, ‘We’re trying to make a better plan, trying to protect the planet for you and the next generation.’”

In his retirement, he adds, “I am still helping out ELAW, while enjoying wild rivers, old trees and big mountains with family and friends.”

As a young boy born in Colombo, Sri Lanka, de Silva was told he was threatening cultural norms because of his involvement with music. “My father was a musician. We would sit together and play instruments as a family,” he says. De Silva’s creative interests were ridiculed and used against him by his peers. By the time he reached university, he had to make a decision. “I had to make a huge choice in my life, between law and playing music,” he said.

At that time in Sri Lanka, there was no higher education for aspiring musicians; he felt torn between continuing to pursue his musical passion with offers from prestigious European universities like Potsdam and Cardiff, or listen to his parents, who, de Silva says, “were honest and full of integrity,” and could not afford to send him to Europe without scholarship funding.

Desperate to pursue his passion, de Silva applied for a band master position with the Sri Lanka Air Force, at the same time receiving an acceptance letter from the Sri Lanka Law College. After a night’s conversation with his father, his path to becoming a world-changing environmental lawyer began.

In de Silva’s final year of college, two ornithologists, Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution and Salim Ali of the Bombay Natural History Society of India, came to Sri Lanka to collect specimens of 24 endemic bird species. Several of the birds were placed on the country’s national “red list,” classifying them as an endangered species close to extinction.

Their tactics of collecting the birds were to capture them through violent measures. De Silva and his colleagues wrote a petition to halt the capture of the endangered bird species. Although his petition made an impact, de Silva realized it was just the start and wouldn’t be sufficient in the long term. “We need something bigger,” he says.

So, as a law student in 1981, de Silva co-founded the Environmental Foundation Limited, the first public interest environmental law firm in the developing world, and later he co-founded the Public Interest Law Foundation in Sri Lanka.

In addition to his law degree from Sri Lanka Law College, de Silva has a masters of laws from the University of Washington and a Ph.D. from the University of Sydney.

De Silva was appointed by the Ministry of Environment as its first legal consultant in 1994, serving for two years and helping draft most of the environmental regulations that are still enforced today in Sri Lanka.

De Silva’s successful environmental work, he recalls, was becoming widely known, leading judges to recognize him as an expert. “I would be sitting in court, minding my own business, waiting for my case to be taken up, nothing to do with the environment — there is some other environmental case going on, causing the judge to ask me to come up and give my advice,” de Silva says.

Alongside his environmental work, de Silva still went on to become a flautist, composer and conductor. His compositions have been performed by orchestras around the world in Sri Lanka, India, United Kingdom, Vietnam and the U.S.

In 2002, de Silva became a legal officer of the environmental claims unit for the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC), which focused on issues of war reparation, security and conflict.

After the first Gulf War, de Silva was recruited — along with scientists and economists from around the world — to try to solve the cost of replacing environmental resources damaged by war and conflict. They worked on calculating the damage to the environment caused by Saddam Hussein after the invasion by setting fire to 700 oil wells in Kuwait.

“Crops died, animals suffered. The oil which was burning spewed out more oil, creating oil lakes — throwing 500,000 barrels of oil into the sea in hope that this oil on top of the ocean could be set on fire to protect when ships were coming,” de Silva says.

While the oil wells burned for months on end, in some areas the thick dark smoke blocked sunlight for weeks. Syria, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Turkey filed billions of dollars worth of claims for environmental damage, according to the American Society of International Law.

“What would be the cost of replacing the damaged environmental resources?” de Silva asks. “There’s no price to it. How do you put the price to it, you know?”

Working with scientists and economists from around the world, de Silva and his collaborators used theories of economics and habitat equivalence to create a legal framework that showcased the evidence for the panel of commissioners considering the case.

The UNCC completed its claim review in 2005 and awarded money to the six countries with environmental claims. The funds were monitored and dispersed over several years.

“This is one example of environmental damage being restored through the international community,” de Silva says.

De Silva previously worked with ELAW supporting and building its global connections and now will leave his imprint as the executive director.

“We’re entering a world with a lot of new challenges. Environmental conservation and protection is under threat more than ever before,” he says, adding that recent wildfires in Southern California and Oregon, and flash flooding in Texas, mean environmental aid is needed more than ever. “My job is to beef up this operation so that we are able to provide the necessary services for the growing number of conflicts that will have to be settled.”

The Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide office is at 1412 Pearl Street. Visit Elaw.org or call 541-687-8454 for more information.