Eating disorders have become a “silent killer” in the U.S., claiming one life every 52 minutes and affecting millions more. Eating disorders aren’t just about nutrition — they can become a severe mental illness with an endless onslaught of obsessive and compulsive thoughts about restricting, binging and purging.

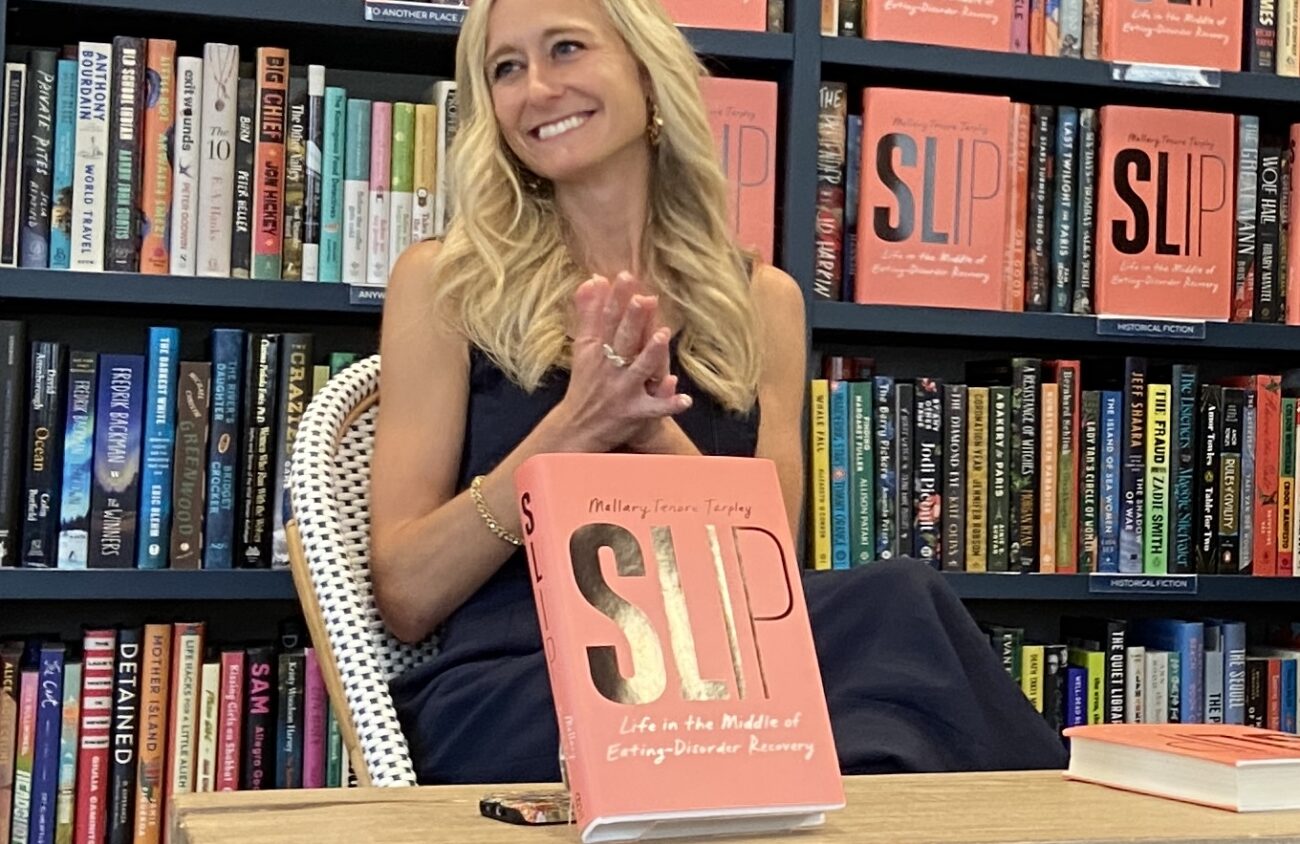

Mallary Tenore Tarpley’s recently published SLIP: Life in the Middle of Eating-Disorder Recovery is one of the most valuable books about recovery that I’ve read. Tarpley brings together expert voices and the leading research on eating disorder recovery while crafting the story through the lens of her own gripping experience with anorexia nervosa. What makes SLIP unique is the focus on recovery as a continuum and the acknowledgement of living in the “middle place” — existing in a spectrum between acutely sick and fully recovered.

Toward the end of the book, Mallary refers to herself as a “heroine of recovery.” I love this because so often when we’re in the darkest vortex of our addictions, we’re desperate for someone — anyone — to see how sick we are and save us. But the reality is that no one can save us. We have to save ourselves. And SLIP can help us do just that.

I had the pleasure of catching Tarpley on her book tour in Santa Monica, and we spoke via Zoom a few days later. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What does the “middle place” of recovery look like for you on a daily basis?

Being in the middle place has largely been about recognizing my vulnerabilities and coming to understand the eating disorder so that I don’t end up letting it defeat me day-to-day. It’s about listening to those periods where I may be called more toward the eating disorder and trying to shift my thinking in terms of making choices that are in service of more recovery.

At your recent book talk you said that “slips” into disordered thinking and behavior are an “opportunity for growth.” What do you mean by that?

So often we stigmatize slips, we demonize them. We think about them as moments of failure. But now I think about the fact that it’s part of the recovery process. I try to maintain curiosity around it. Why did I slip? Who can I talk to about this? And how do I get back up again? So when I can do that sort of analysis around a slip and have more self-awareness, it actually helps me to move forward in my recovery.

In recovery communities, we often talk about applying “tools of recovery.” What recovery tools do you find most valuable?

I sometimes rely on tools like mantras. In my recovery, I’ve learned to develop my own voice and my own line of thinking. And so a lot of times when I have eating disorder thoughts, I’ll think “opposite action.” Let me do the opposite of what the eating disorder is trying to tell me to do.

Research has shown that writing about painful experiences can help the writer heal. How was writing this book healing for you?

Writing my book was therapeutic. Writing is this process of discovery that helps me to be more self-aware and helps me to put words to my recovery. Journaling was an important part of my writing process because it’s important to have a place where you can write for an audience of one — meaning yourself — where you can just unabashedly write and not be afraid of what other people may think of it. It’s a place where you can share emotions without shame. Once I’ve been able to think through that process I can come to the page with a greater sense of what I want to share publicly. So that process can help us to make connections between the stories we tell ourselves and the stories we want to tell the world, and through these connections we can find meaning. If I hadn’t written about the middle place, I don’t know that I could speak articulately about it or that I would even feel comfortable talking about my eating disorder.

Certain personality traits, such as perfectionism and OCD, are common in those with addictive disorders. In the book, you discuss temperament-based therapy (TBT), which works to turn those traits into strengths. How have you done that in your own life?

It’s a matter of figuring out how to use your traits rather than trying to get rid of them. Perfectionism, for instance, fueled my eating disorder when I was sick. I recognize that I’m still very much a perfectionist, but I don’t like to say that I’m a “perfectionist in recovery” because I don’t need to be in recovery from my perfectionism. It’s just part of who I am. And so for me, perfectionism helps drive me. It helps me to succeed professionally. I recognize moments where it can mess with my mind and be potentially harmful, but that’s something that’s not going to set me back anymore. I can have the thoughts, but then still be able to move beyond them.

Coda. Tarpley closed her book talk saying that she hopes readers feel ”seen and heard” after reading her memoir. Indeed, this was my experience with reading SLIP.

Nicole Dahmen is a professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication and the Clark Honors College. The book is available for purchase from Simon & Schuster and all major online booksellers and of course ask for it at your local bookseller.