Good Old American Music?

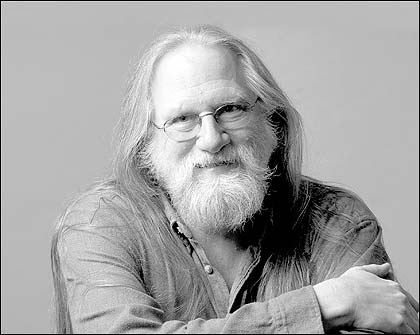

Todd Barton creates African Company soundscape

By Suzi Steffen

Picture the sounds of New York, circa 1821: cows, pigs, horses, carriages, boots glopping through mud and water. Tony white folks play Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann as their servants, including a few last N.Y. slaves and a lot of free blacks, perform their labor. In the evenings, some of the African-Americans will travel to the African Grove, a theater company founded by blacks, for blacks, with black actors and directors, costume designers and scene painters.

|

When Todd Barton, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s resident composer, started to imagine creating the sounds of the African Grove for the OSF’s The African Company Presents Richard III, he found himself a bit stumped.

“White culture was just totally appropriated from Europe,” he says. “Likewise, the Africans had brought their own music, which was of the djembe and the talking drum.”

The mostly West African slaves of the U.S. and the Caribbean, and their descendants, including many of New York’s free men and women, used the talking drum to communicate. That drum originated, probably, within the Ghana Empire. The djembe, or jembe, meanwhile, might have originated within the Mali Empire, and it’s got a deeper voice. Carlyle Brown’s script for The African Company Presents Richard III calls for both kinds of drums, so Barton knew he needed to write music for them.

The character of Papa Shakespeare, played by Charles Robinson, had been a griot both in West Africa and in the islands before he arrived in the U.S., and he carries his talking drum with him to help translate meaning from one group to another. “I imagined a talking drum in New York in the 1820s was possibly a novelty, possibly unusual,” Barton says.

As he researched the sounds, he also learned that it’s likely Africans brought the banjer or banza — aka the banjo — first to the Caribbean islands and then the U.S. “We were going to use one in the play, but it’s too cumbersome,” he says. “It’s a huge gourd with skin.”

Instead of having a character play the banjer, Barton plays the instrument himself, mixed with a drum sample set, for the music under scenes between Jimmy Hewlett (Kevin Kenerly) and Ann Johnson (Tiffany Rachelle Stewart).

For the white impresario Stephen Price (Michael Elich), who strongly believes that he is a cultured, important man, Barton used opera, which contemporary U.S. audiences may interpret as a bit stuffy or snobby, and for the Irish constable (who has no name, and is played by Mark Murphey), Barton placed some subtle Irish fiddle music in the mix.

He also wrote a waltz for a couple of scenes involving Sarah (Gina Daniels), but it’s not the kind of late 19th-century waltz some may think of — “it’s not the ‘Blue Danube,’ it’s not Strauss,” he says. “This is based on country dances.”

Barton needed to show that the African traditions of music, including the rhythmic, deep djembe and the stringed banjer, met and sometimes clashed with European traditions, both folk and classical. He says that writing the music was actually not so hard, considering that much of the script contains cues for this clash.

“The juxtaposition of these two major cultures, that was the point for me, musically,” Barton says.