Occupying Wall Street for Dummies

An interview with Benjamin Brubaker

|

|

|

|

Benjamin Brubaker (Benjah) has been a crisis worker at the White Bird Clinic in Eugene for the past five years. At White Bird he has filled many roles including volunteer coordinator, grant writer, teacher, counselor on the 24-hour hotline, and member of the mobile team (CAHOOTS) dispatched through the Eugene police-fire-ambulance communications center.

Before working at White Bird he spent nine months serving as a member of the 24-hour security team at a relief kitchen/camp set up in the parking lot of a demolished building immediately following Hurricane Katrina. He also spent four years as a counselor at a lock-down residential treatment facility for teen boys.

He is currently a co-founder and resident of the Heart and Spoon community house in the Friendly Street area of Eugene.

At the onset of the Occupation, Benjah was instantly intrigued by the live-in element of this movement. He (kind of obsessively) followed the live-stream podcasts that emerged (occupystream.com) as, city by city, the Occupation began to expand. Obviously, Benjah was interested in the political ramifications of the movement, but he was especially fascinated by the social organization of this brand new, exponentially growing conglomeration of people from all spectrums of life.

When two of his friends unexpectedly offered to sponsor his trip to the New York Occupation, Benjah immediately accepted.

The following is an interview with Benjah by his wife after his 10-day occupation at Wall Street. During his stay he worked in the medical tent as a crisis worker and contributed to the eternally evolving structure bent on keeping the Occupation peaceful.

Jesika: I have noticed that, when referring to the Occupation, people tend to avoid the term “protest.” How is the Occupation different from a protest?

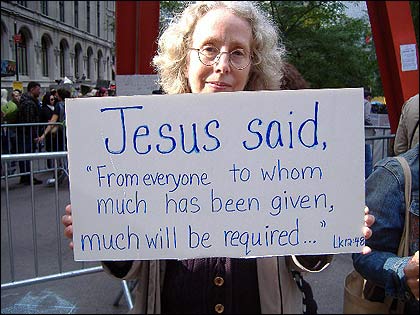

Benjah: Because a protest usually has a singular target or demand. The Occupy movement encompasses far more than that. It is not only about sharing ideas, but about activating them … trying them on for size. The Occupation itself is a living prototype of self-governance and community.

The Occupation is not intended to stop or block any single issue or event. Its purpose is to collectively critique and identify what is broken in our society and to reach consensus about how we should proceed.

Jesika: It could be argued that this “prototype” of self-governance that is being created at the Occupy site is idealistic in the sense that many of those who occupy are not working a job. The food and medical supplies etc. are being supplied for free. Does this make it an “unrealistic” society?

Benjah: Corporate lobbyists throw millions of dollars toward influencing politicians and swinging elections in their favor. In the Occupy movement, people give what money they can. Others volunteer their time as doctors, chefs, organizers, or computer techs … whatever their skills are. People want to support the full-time occupiers across the country because the occupation site has become the voice of “regular people” across the world.

My plane ticket out to Wall Street was paid for by a few of my friends who stepped forward because they did not have the ability to leave their jobs, yet they wanted to forward the movement and they felt that I would be a good representative and organizer.

People are delivering food and supplies from all across the world to Occupation sites. What I hope I’m conveying is that the Occupation does not only consist of jobless individuals who hang out all day in a campsite. It is much, much larger than that.

The beauty of this movement is that its roots reach out from each Occupation site and draw energy from every corner of the globe. We are sharing resources, ideas, solutions, organizational strategies, and a general feeling of solidarity that no government or corporation can compete with.

Jesika: So this movement goes far beyond politics?

Benjah: Exactly. This movement feels far more holistic than any “protest” I’ve ever taken part in.

Jesika: How is the environment of the Occupation different from our accustomed day-to-day environments?

Benjah: The most apparent difference is the willingness of nearly everyone, in this radically large group of individuals, to instantly respond to issues of conflict or escalated situations. Any time two people argued or talked loudly, the crowd immediately activated to intervene and de-escalate the individuals who were at-odds.

Jesika: How did they go about this de-escalation process?

Benjah: The most common way is to use a mic check.

Jesika: What is a mic check?

Benjah: One person yells, “mic check!” and the surrounding crowd shouts back, “mic check!” Then the individual speaks short phrasings of words that are repeated and amplified by the crowd … so, in a sense, the crowd becomes a “microphone” for the speaking individual.

Jesika: What short phrases do they “amplify” during a conflict?

Benjah: They usually restate the positive social contracts such as, “We all need to respect each other. This is a peaceful protest. Let’s keep it peaceful.” Or, “We are all here for the same reason. Don’t let outside forces divide us.”

Jesika: What if the mic check doesn’t work? What’s the next step in the de-escalation process?

Benjah: After that, people called for “de-escalation” (another name for security) or “mediators” (on site nonviolent-communication trained mediators) or “support” (mental health crisis workers). Surrounding people yell these words out and the people with those qualifications respond to the scene.

Jesika: Do these crisis workers and mediators have any sort of organizational structure?

Benjah: All of these working groups meet constantly to resolve the on-site issues as well as issues with the outside community. Each of the groups I mentioned form a “safety cluster” which continuously examines on-site policies and procedures to ensure that everything flows as effectively as possible. As it has become increasingly obvious that outside security systems (such as the police) are not interested in helping those involved with the Wall Street Occupation, the tightening of on-site security has become even more crucial.

Jesika: You said that the NYPD is not helping those involved with the Occupation? Would you care to discuss that further?

Benjah: It’s a strange duality because the Wall Street Occupation has an overwhelming police presence, yet when crimes or issues occur that require police action, it often takes the reporter of the crime numerous attempts before finding an officer who will actually take the occupier’s concerns seriously. Sadly, it is clear that the police are not there to protect everyone, but to protect the 1 percent.

Jesika: When you say, “an overwhelming police presence,” what kind of numbers should we be visualizing?

Benjah: Usually no less than 20 police vehicles surrounding the park and 20 to 60 police officers. They definitely add an ambiance of intimidation to the site.

Jesika: And can you describe a specific scenario to exemplify your statement that the police do not take the occupier’s safety concerns seriously?

Benjah: Yes. I immediately think about a young female who was hit in the face by a male assailant. The assailant arrived from off site. The victim solicited at least four officers before finding one who would arrest the assailant for assault.

A few days later, the assailant’s friends returned to the scene to threaten and intimidate the woman because of her involvement with the police. She contacted seven or eight officers, all of whom gave her the run-around, refusing to take action.

Despite the fact that it was a clear case of intimidating a witness, the police didn’t become motivated until a lawyer (who happened to be on-site) and I (acting as the mental health worker) made a fortunate contact from the DA’s office.

Another time, a gentleman (identified by residents of the area as a local drug dealer) walked through camp for five or six hours, in the middle of the night, screaming (in a mocking way) lyrics to a Beatle’s song, “so you say you want a revolution!” This man would not stop, even after mediators, mental health workers, and peaceful occupiers all tried to intervene.

Despite the fact that an egregious number of police officers were present, not one officer took action. Doesn’t this seem like an instance in which police would have responded if it had been a different crowd or venue? What if someone had been trying to incite a riot at a football game?

And, one final example is the tendency of the police and fire department to activate their sirens, randomly, as they drive along streets that are immediately adjacent to the Occupation, and they do this predominately in the middle of the night. I worked the overnight shifts so I personally witnessed numerous instances of sirens going off just as the vehicles drove along the Occupation site and then the sirens being cut at a distance of only one or two blocks away. It doesn’t make a lot of sense. I can only assume that the drivers of these vehicles are trying to intimidate the occupiers or to deprive them of sleep.

Jesika: Are the officers on site rude to the Occupiers?

Benjah: Not all of them. Some of them communicate pretty amiably. Others will not make eye contact and ignore all efforts of communication.

Jesika: Do you think that anything positive has resulted from the lack of police involvement with the Occupation’s in-house affairs?

Benjah: Absolutely! The Occupation deals with its own issues concerning substance abuse, interpersonal conflict, and violence (verbal and physical). The realization that we are, essentially, on our own in these areas helped to construct an unbelievably tight-knit group.

In fact, the Occupation has become a harbor for so many skilled professionals that many occupiers don’t even want to call outside authorities because it is vastly apparent that the Occupation has better resources to effectively handle most situations. Especially right now, most social service institutions are underfunded and understaffed while facing impractically large case loads. Their ability to give high quality service to the community is waning. Many occupiers no longer trust outside institutions and security apparatuses to function with the best interest of the individual in mind.

If someone at the occupation shows up drunk, the staff on site are likely to find them a place to lie down or to take them to the medical tent for stabilization and monitoring. On a normal day in the city, the police would take them to the emergency room where they would likely be over stimulated, faced with frazzled and overloaded staff, and then dealt a humongous bill.

Jesika: I heard that the New York occupiers were not allowed to use tents. I’m sure that’s only one of many discomforts about being a full-time Wall Street occupier. Can you tell me about some of the day-to-day difficulties?

Benjah: The absence of bathrooms is a big one. One of the city’s primary complaints regarding the Occupation was sanitation. But when the site inquired about Porta-Potties, they were told that the potties would be immediately confiscated because a permit could not be acquired for multi-day events.

Without Porta-Potties, everyone is forced to use the facilities in local restaurants, primarily McDonalds, Subway and Burger King. In reaction, Burger King ruled that no one can use the bathroom without ordering a full meal. Even in restaurants that haven’t made that regulation, occupiers still feel compelled to purchase something. No one wants to give the Occupation a bad reputation.

Mediators are working constantly to resolve this issue because we want local businesses and chain restaurants to feel included in the Occupation.

This entire scenario has created a situation where having to go to the bathroom just becomes “a state of mind” for most occupiers. We just carry the discomfort until we absolutely have to deal with it. It also leads to inconsistency with staff because, especially for women, having to use the bathroom becomes at least a 30 minute process. This irritation even leads some people to decide against occupying at all.

Jesika: Are the Wall Street occupiers allowed to use tents?

Benjah: At first there was a “no tarps at all” rule. That rule was eventually relented and tarps could be used for covering equipment and for people to wrap themselves in order to sleep. But this did not occur until several occupiers had already been arrested for the cause.

The first tent was the medical tent, used to cover equipment and to ensure patient confidentiality during medical issues. Within two or three days the police threatened to arrest the medics if the tarp wasn’t taken down. At the last minute, the Rev. Jesse Jackson arrived and said, “get your ass out of here” to the cops. The police completely gave up after that and haven’t made any more attempts to take down the medical tent even though the very next day a larger medical tent was erected.

The lack of police interference on this issue has led to more tents being put up. Now some people are even using tents for personal comfort.

Jesika: What did you enjoy most during your occupation in New York?

Benjah: Walking around in a crowd that large and listening to almost every person engaged in intense political, social and economic discussions … debating root issues and problems as well as the merit of various solutions for the repair of what is broken in our society.

Jesika: In what capacity do you see yourself contributing to the Occupation now that you’ve returned to Eugene and your full-time job?

Benjah: I plan on organizing more crisis intervention trainings to help people feel more prepared for the crisis and escalation that will continue to erupt on occupation sites due to the stressful environment. I’m always working to expand people’s awareness and comfort level surrounding mental illness, especially among the homeless population, and that’s very relevant at the occupation site.

I’m also going to take what I learned from the few marches I attended in New York, and help to organize similar consensus based marches here in Eugene. And finally, White Bird Clinic (the crisis center where I work) will continue to support the medical side of the occupation efforts.

Jesika: Do you think that the added time and energy that it takes to reach decisions by consensus is going to work for or against the Occupation?

Benjah: It’s working right now. It might be time consuming and emotional and messy, but the fact is … it’s working. Are there ways the process can be streamlined and still keep its integrity? I think so. One of the new models being activated in NYC is a spokes-council model. It is a blending of the consensus process with representatives from the different working groups meeting together to iron out proposals and reach consensus in a more streamlined way. Other models will be proposed, attempted, and then either built upon or discarded.

Again, this movement is about the conversation. It is not an assembly line product or a set of soul-less governmental procedures. We will all see what emerges in time.