Some people dream of sparkling granite countertops, spacious pantries and glossy whirlpool tubs set next to enormous showers tricked out with the latest technology.

Rhonda would just like a bathroom, and Emerald Village Eugene (EVE), a new proposed village of tiny houses, could give her that along with the stability she and others need to get back on their feet. Currently, she lives in Opportunity Village Eugene, but because subsidized, low-income housing is difficult to find, she and her husband need another transitional step — which is where EVE comes in.

“We used to live on 160 acres,” says Rhonda, who didn’t want her last name used in a story about her turn of luck. “[We had] a nice three-bedroom house in Colville, [Washington]. We were what you call regular Americans.”

In 2009, during the worst of the recession, Rhonda and her husband were laid off. “The town we lived in had 300 people and no economy,” she says. “We were living on this farm and it was all we’d ever wanted. We’d still be there if we had kept the jobs we loved, but it all just went away.”

Job hunting for five years didn’t turn up a single position, and Rhonda knew checks were going to start bouncing. In an effort to protect their rental history, Rhonda and her husband made the difficult decision in March of 2014 to sell all of their possessions and begin living in the forests of Oregon at free campgrounds until they could find employment.

With their limited means, it was impossible for Rhonda to drive back and forth from the forest to Eugene where she could find a job, but the forest was safer than living on the city streets.

Opportunity Village Eugene (OVE) was, exactly as the name implies for them, a chance for a hand up. Thirty quirky tiny homes, an outdoor kitchen, bath house, laundry and a large yurt tucked safely behind a chain-link safety fence makes up Opportunity Village.

At Opportunity Village, Rhonda and her husband found a safe place to gain some ground, but they hope to bring to fruition a new program — Emerald Village Eugene, which still has a number of hurdles to clear before it becomes a reality.

In Eugene, the waitlist for single-occupancy low-income housing can be two to four years — a wait Andrew Heben, co-founder of OVE, believes is too long.

“Opportunity Village is a transitional place to get people off the streets,” Heben says. It’s a good first step, he says, but it is time to take the next step.

“What we’ve found is that a lot of folks have a modest amount of income but they can’t necessarily afford the cheapest rent, and the Section 8 [subsidized housing] waiting list is closed right now,” Heben says.

Emerald Village Eugene would bridge that gap between the transitional housing at Opportunity Village and traditional low-income housing.

Heben’s goal is to provide permanent tiny homes that would rent for $250 per month, something Heben says he believes is affordable and sustainable.

By using volunteer labor and keeping the units simple and small, Heben and the board are hoping to complete EVE without reliance on public subsidies.

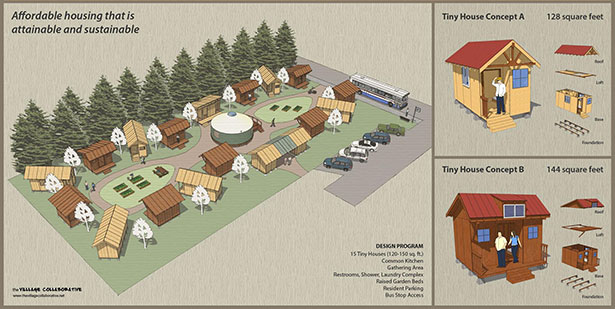

According to the Opportunity Village website, Emerald Village will provide a grassroots model for permanent, affordable housing. The community will include tiny (140 to 250-square-foot) houses each with a kitchen and bathroom, supported by common gathering and gardening areas.

The mockup Heben and Alex Daniel, designer and chief builder, have created includes 15 tiny houses costing around $15,000 apiece to build.

Popularity of the “tiny house” movement and the goodwill of the project have inspired local architects to sponsor the design, construction and materials of seven of the 15 units.

Villagers would be required to contribute 50 hours of volunteer time to the project to live in one of the Emerald houses.

Heben and Daniel’s goal for the village is to create an aesthetically pleasing community and foster self-reliance for villagers through the creation of a co-op.

The first portion of the villagers’ “rent” would go to maintenance and utilities, while the remainder would go to equity. With equity, villagers could sell their shares back to the nonprofit when they leave, giving them the upfront costs on a rental or a down payment on a house if the villager finds steady work.

For Rhonda, knowing that a portion of the rent would be put away for them if they ever decide to move is comforting. “People have such a hard time saving money because after they pay their bills they still owe a couple bills,” she says. “It’s a juggling act.”

Finding a location for EVE will be one of the biggest hurdles for the project. Some neighborhood residents have already voiced their concern about having the development in their neighborhood. Rhonda understands such concern, but like the individuals in those neighborhoods, she is hoping for a safe place that she can call home.

“EVE is permanent housing for very low-income people, people just like them. The misconceptions they have about homeless people who are causing problems are not the people who live in [OVE].” Rhonda says. “I understand their frustration with what they are dealing with and I try to see it from their point of view. But I wish they would not pass judgment and think we are the same ones that are causing problems. We are just normal people, too.”

Although there are still many hurdles for the project, Heben, Daniel and Rhonda say they hope they will break ground soon. EVE is currently fundraising on crowdrise.com. As of press time, the website has raised nearly $8,000 of its $15,000 goal.

“We’ll have electricity, heat and a bathroom. To us it will be just like going back to normal, so that we can function back into a more mainstream society,” Rhonda says.