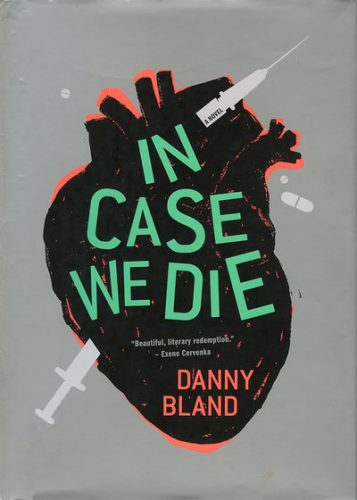

Entering into the gloriously tattered tradition of strung-out criminal lit ranging from Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn to Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, Seattle rocker turned author Danny Bland has written a novel that reads like a beastly scream into the dark mythology of ‘90s Seattle — a gilded wasteland where junkies reared on Iggy and Sabbath turned filthy power chords into gold and cosmonauts of the apocalypse pimped hip to the culture vultures. In Case We Die (Fantagraphics Books; $26.99) is by turns filthy and wrenching, funny and violent, as Bland tells the story of a pair of star-crossed lovers who are driven together, and then apart, by the ravenous needs that consume them both. Scenes of lust, degradation and self-immolation are interspersed with a kind of narcotic slapstick that reveals the insane logic of addiction, and beating below it all is, yes, a love story that is no less moving for being utterly down and dirty.

Here we have the narrator, Charlie Hyatt, a heroin addict who works the night shift at a downtown sex shop with its “blinking lights everywhere — beckoning you to phallic monstrosities too gruesome to imagine handling, much less inserting.” During his off hours, when he isn’t chasing down dope, Charlie is tangled up with his girlfriend, Carrie Finch, a rising rock star with a serious death wish. Every morning the two of them wake up to Carrie’s perpetual suggestion of suicide, that today might be the day, to which Charlie can only implore, helplessly, “not yet.” This sounds like dark territory, and it is, but Bland’s prose — an artful blend of sharp comedy, poetic insight and deadpan patter that channels a kind of hardboiled neo-noir — is like a fluttering flashlight illuminating the darkness.

As Charlie’s life spirals out of control, and the gnaw of his addiction pushes him to increasingly reprehensible acts, we begin to see cracks in the tough-guy exterior; his tone is confessional, self-deprecating, buoyed by cosmic sense of humor that reveals his underlying humanity. Here’s how Charlie describes rifling the drugs of a terminal cancer patient who lives in his building: “The first time I went over there, I was being a good citizen, honest… But then I have that thing about medicine cabinets. When I opened his, everything changed. There they stood, like tiny glass soldiers fallen into rank, dozens of bottles of morphine. Maybe I heard a chorus of angels, maybe I didn’t.”

This is tough stuff, the brutal honesty of a man driven to wit’s end by a hunger that, in the final tally, will only be satisfied by annihilation. And hindsight, with its unforgiving clarity, is always a bitch: As Charlie makes stuttering steps toward recovery in a twelve-step program, we watch him grapple with the wreckage of his life. In keeping with the narcotic nature of its subject matter, In Case We Die is episodic and hallucinatory and fast-paced, flipping back and forth in time but always hurtling toward its final act, which is at once tragic and liberating. But, unlike so much downbeat junkie fiction, Bland’s novel never bogs down in overweening self-pity or mealy mea culpas; his tone is one of hard-won acceptance for life in all its glorious fuckery, and there is joy to be found in his embrace of that long, hard path that leads upward to light. Not for the weak of heart, this is a novel that is glued together by the most basic substances of life — sweat, semen, blood, shit, spit — but it is always slouching toward survival.

Bland and I ran in some of the same circles in Seattle in the ‘90s, and our paths intersected every once in a while; I think we’re both a bit surprised, and grateful, that we made it out alive. I’m especially glad Danny punched through to write a book like In Case We Die (he’s also published a beautifully illustrated book of streetwise haiku poetry, I Apologize in Advance for the Awful Things I’m Gonna Do, published by Sub Pop). He was a damn fine bass player, but it seems that, in writing, he’s found his truest voice — the funny, sad, strong voice of a man who’s seen it all, and who has the balls and the humility, not to mention the talent, to send back reports from the bitter edge.