This story begins with a simple request for information. Before long, it veers into murky waters about freedom of information and the public trust, and potential violations of both in Eugene and statewide.

The story ends in a snarl of unfortunate answers with, perhaps, a shard of hope.

Little did we know that one narrow request would end with a tumble down the rabbit hole into the absurd world of public records law in Oregon, leaving us with the question: Do you, as a citizen in a democracy, have the right to know?

This past winter, Eugene Weekly submitted a public records request to the city of Eugene in the thick of the Kesey Square controversy, an issue both this paper and The Register-Guard had been covering regularly for months.

The controversy in question stemmed from an Oct. 12 executive session — a meeting closed to the public — at which City Manager Jon Ruiz brought a private proposal to purchase the publicly owned Kesey Square, also known as Broadway Plaza, to the Eugene City Council.

In an unorthodox jumping-off point for a property transaction, Ruiz was asking City Council to consider a private offer to buy a city square that had not been deemed surplus land; a city square that had not been publicly listed for sale; a city square of which hundreds of thousands of tax dollars were invested to pave in brick and beautify with art (but, oddly enough, not to maintain it); a city square that had been “forever dedicated to the use of the public” by a 1971 deed.

The interested buyers, a private group led by Rowell Brokaw Architects — the same firm Ruiz handpicked to work on City Hall — wanted to build (and seemingly still does) high-end apartments with ground-floor retail on the square.

Some in Eugene supported the plan to sell Kesey Square, calling it an underperforming “empty lot,” but citizens were suspicious of giving up valuable public land, let alone a landmark, in the heart of downtown.

EW had questions about the process, or lack there of, surrounding this public parcel of land and how such a development proposal came about.

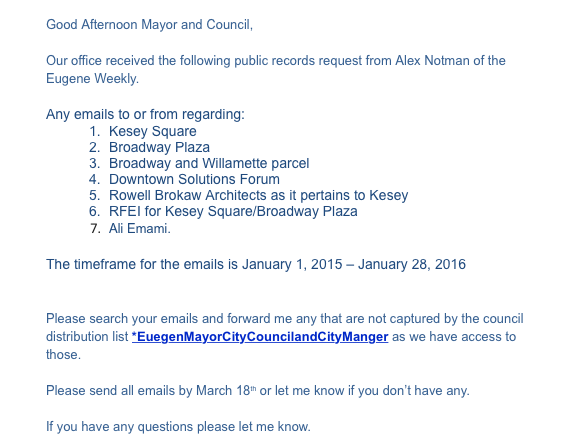

On Jan. 27, 2016, EW submitted a public records request for “any emails from or to City Manager Jon Ruiz, Assistant City Manager Sarah Medary, City Planner Nan Laurence, Mayor Kitty Piercy, Eugene City Council regarding: Kesey Square/Broadway Plaza/Broadway and Willamette Parcel; Downtown Solutions Forum; Rowell Brokaw Architects, RFEI for Kesey Square/Broadway Plaza; Ali Emami.” The timeframe was 2015 and 2016.

The city refused to waive the fee, as it has the discretion to do, responding that EW’s request was not in the “public interest,” and set the price at $447.20 for collecting emails.

EW paid the fee Feb. 25 and was told to check back in a week. One week turned into two, two weeks turned into a month, a month turned into — well, as of this issue (May 26), EW is still waiting for the entire request — essentially a search for emails containing keywords — to be fulfilled.

To be sure: This story is not about what EW’s public records request reveals, but rather what the journey to obtain it does. Eugene’s process for public records is troubling, but it is in no way unique to our city. Eugene, and Lane County for that matter, echo the dysfunction that starts at the state level; call it trickle-down obfuscation.

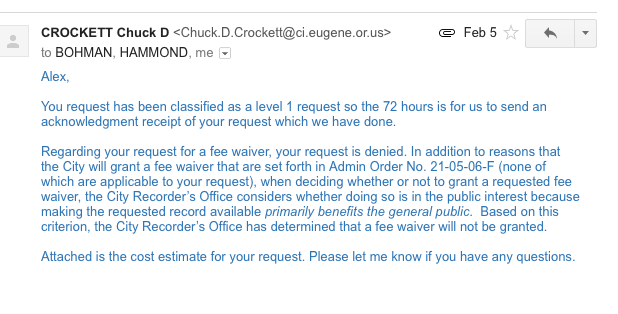

[Below: The city’s public records fee waiver denial for EW‘s request.]

F is for Oregon

“A 2007 study of government transparency in the 50 states gave Oregon an ‘F.’”

Those are the opening words of the damning 2010 Attorney General’s Government Transparency Report, known among public records wonks as the Kroger Report, after then-Oregon Attorney General John Kroger.

In 2015, the Center for Public Integrity — a nonprofit investigative journalism organization — also gave Oregon an “F” for “public access to information.”

Recently, transparency in government came into sharper relief statewide in the aftermath of the fall of Gov. John Kitzhaber. In its wake in early 2015, the new Gov. Kate Brown ordered an audit of public records via her three ethics reform bills, but many saw the move as two-faced, accusing Brown of delaying a public records request Oracle made for Kitzhaber’s emails while in office — apropos of the lawsuit between the state and Oracle, the tech company behind the comical failure that was the Cover Oregon health insurance website.

Regardless, the audit came back with a message: Oregon’s public records system needs improvement.

Oregon has failed the public records test, but don’t let the decidedly unsexy term “public records” lull you into glazed-over apathy. These aren’t just dusty stacks of documents in a cubicle somewhere, but the paper trail that follows our elected officials, as well as the staff they bestow with the responsibility of carrying out their wills.

Public records can reveal a government body functioning well and above-board.

Or they can tell you where the bodies are buried, who buried them and how much it cost.

Oregon’s current Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum, appointed by Kitzhaber (and married to former Willamette Week publisher Richard Meeker), explains the importance of access to public records: “I think people have a right to know what their public servants are up to,” she tells EW. “You elect me to do a job, and I don’t think you’re electing me to do that job in secret.”

The public’s right to access public records serves a purpose: to keep government accountable and transparent. And when a public agency throws up a barricade to accessing public information, red flags go up, especially for a newspaper.

Red flags have gone up for many around the state — journalists, public records lawyers, citizens, the Lane County District Attorney’s office and the AG’s office — and they’ve been planted into three areas that need overhauls: a glut of exemptions (more than 500 and counting in Oregon — more than double that of the next highest state, Florida), fees and deadlines.

On Oct. 23, 2015, Rosenblum announced the “Attorney General’s Public Records Law Reform Task Force, a group designed to review and recommend improvements to Oregon’s public records laws.”

Rosenblum and Michael Kron, special counsel to the attorney general’s office, are traveling around Oregon to gather testimony at public hearings with some of the task force, including an array of about 20 stakeholders like State Senator Jeff Kruse and Oregonian investigative reporter Les Zaitz.

The task force has been to Salem and came to Eugene May 9. Rosenblum will hold Portland’s first public hearing May 26, and the task force will host a public meeting in Salem May 27.

For the 2017 legislative session, the task force will make recommendations to the Oregon Legislature, which has largely opposed suggested reforms to public records laws in the past. If the Legislature votes to adopt the recommendations, however, real reform could come to Oregon’s state agencies. And as the states go, so will the counties, municipalities and, perhaps, even Eugene.

There’s No Sunshine When Frohnmayer’s Gone

In 1973, in the wake of the Watergate scandal, Oregon joined many other states in enacting sunshine laws, or Public Records and Public Meetings Laws, as a way to keep government transparent, accessible and accountable to the public.

Yes, Tricky Dick paved the way for transparency and the Oregon Public Records Act (OPRA). And special interests have been chipping away at it ever since.

“When I first started as a reporter in 1984, the Oregon Public Records law was still universally, for the most part, useful,” Brent Walth explains. “What I’ve seen over time is an evolution of government agencies shifting in their posture to: ‘We are going to thwart and frustrate and block as many of these requests as we can.’”

Walth, a Pulitzer-winning editor formerly of the The Oregonian and Willamette Week, is now an associate professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication. He is currently teaching his students about public records law.

“It’s getting worse all the time,” Brent Walth says. “I’ve yet to see an Attorney General since [Dave] Frohnmeyer who was serious about enforcing the spirit of the public records law. That sends a loud message across all state and local government that if you want to hide something, you can do it.”

Bill Harbaugh — University of Oregon economics professor, author of UO watchdog blog UO Matters and public records advocate — recalls Frohnmayer’s tenure as AG fondly as well.

“He was very enthusiastic about enforcing the law,” Harbaugh says. “He would tell state agencies, ‘Jump to it.’”

Under Frohnmayer’s reign (1981-1991), Walth recalls, the Attorney General’s office decided in favor of disclosing public records requests in dispute about 65 percent of the time.

“After Frohnmayer, that changed dramatically,” Walth says, “particularly under Myers.”

Myers, as in Hardy Myers, AG from 1997 to 2009, was known for “rubber-stamping” denials to public records requests. Harbaugh calls Myers “notoriously bad” on enforcing public records law.

Following Myers as AG came John Kroger (2009 to 2012), of the 2010 Kroger Report, which made sweeping suggestions for reforming OPRA. While many in pro-transparency circles supported the suggested reforms, a storm of lobbyists for state and local agencies came down against the recommendations.

“When Attorney General Kroger was in office, he was pushing very strongly to try to reform the Oregon Public Records Act,” lawyer David Bahr says. “He did not succeed.”

Bahr is a local public records and FOIA (Freedom of Information Act, or federal public records law) attorney who is currently serving on the FOIA Committee under the National Archives and Records Administration. For more than two decades, Bahr has lectured nationally about state and federal public records laws.

The Kroger conundrum leaves reform advocates like Bahr, Harbaugh and Walth skeptical that any overhaul is possible in Oregon, but current AG Rosenblum, with ostensible support from Gov. Brown, has picked up the torch regardless. She says the AG’s office has a more narrowly focused approach than Kroger, who presented more of a far-reaching “omnibus” to the Legislature.

“I’m not Attorney General Kroger, and I don’t necessarily plan to follow what he did,” Rosenblum says. “This is really a whole new effort here, and I want to be very clear because [Kroger’s effort] didn’t work out.”

The Great Exemption Bloat

There’s a reason Rosenblum’s task force is addressing exemption bloat first: It has the best chance of reform because all sides seem to be for it.

The Kroger Report shows how exemptions — or codified reasons allowing government officials to withhold sharing public records — are not just a concern for the public but also government officials, who themselves have trouble keeping track of them.

“There are a number of exemptions that I’m glad that they’re reviewing to see that things are handled consistently,” says Lane County District Attorney Patty Perlow, who decides on appeals for local public record request denials.

In 1973, when OPRA was first instated, Oregon had 55 exemptions. In 2010, the Kroger Report’s count was 403. As of 2016, Oregon’s exemption count has ballooned to 544. In contrast, FOIA has a total of nine exemptions (granted, they are broader categories).

“Everyone who addressed the subject seemed to agree that re-organizing and compiling various exemptions — which are scattered throughout the statute books — would significantly improve the law and reduce costs,” the Kroger Report states.

Rosenblum says the number of exemptions is high because of special interests.

Bahr agrees: “The problem is — what happens every legislative session — the lobbyists come and insert more exemptions.”

Before 2016, researching exemptions was a nearly impossible task. Now, for the first time, Kron and his team compiled a spreadsheet with all 544 exemptions in one place, which can be found on the attorney general’s website.

“Before that spreadsheet existed, you would have basically had to figure out where in the tens of thousands of pages of statutes,” Kron says. “It’s the most complete catalogue ever.”

While it’s an improvement to have exemptions searchable in one place, Walth maintains that government officials continue to withhold public records by citing an exemption, even though they are not always required to. While some exemptions are not up to the discretion of the officer, many exemptions are.

“The agency is not required to withhold records,” Walth says. “They simply choose to 99 percent of the time.”

But as Harbaugh points out: “The fundamental problem isn’t the exemptions; it’s the fees.”

Cash Money

The city of Eugene charged EW $34.40 an hour for both City Manager’s Office staff time (at five hours) and Planning staff time (eight hours) to collect emails. An interesting price point, considering that deputy recorder Chuck Crockett simply sent an email to Ruiz, Medary, Laurence, Piercy and City Council and requested they search their own emails.

Yes, the subjects in question were directed to search their own emails and forward Crockett what they found relevant.

The Kroger Report states that many other states “cap the hourly rate that can be charged for staff times, at levels that range between $10 and $25 per hour.”

Abuse of fees by public officials was the largest concern of the journalists, lawyers and citizens EW spoke with about Oregon’s public records law.

“Agencies in Oregon routinely use fees as a barrier to access,” Bahr says.

Fees can include anything from copy charges to the hourly rate of lawyers brought in to review documents before being released to the public.

Walth says government bodies use “punitive fees to get records that already belong to us.” He brings up a point addressed in the Kroger Report:

“The system of charging fees for public records provoked a significant amount of criticism in meetings around the state. Some raised a fundamental question: Why should the public have to pay the government to produce copies of documents that are already owned by the public?” the Kroger Report states.

It continues to explain citizen concerns about fees: “Even among those who recognize that fees may be appropriate, there is a perception that government officials can effectively block disclosure by imposing high fees for records.”

That’s not to say all fees are unwarranted. Fees are typically charged for compiling a request and, depending on the nature of the request, there are additional charges for printing or duplicating.

[Below: The email to City of Eugene’s Mayor and City Council where the nature of EW’s request was altered.]

And, as Bahr points out, many smaller municipalities do not have staff or resources dedicated to completing public records requests.

So, for example, if a public records request is made by a group of researchers who will use the information to benefit the population at large, that should, according to the spirit of the law, qualify for a fee waiver — because it is in the public interest.

However, if a public records request requires hours of manpower and only serves the personal interest of the requester, many agree that in such a case a fee is appropriate.

Another common complaint is the lack of standardization of fees in Oregon. Public bodies can essentially charge what they please.

Perhaps the most prominent local case of out-of-control charges is that of In Defense of Animals v. OHSU, or Oregon Health and Science University, a case that Bahr worked on.

In the late ’90s, In Defense of Animals, an animal protection org, made a public records request about OHSU’s experimentation practices on animals after a former OHSU employee alerted organization to unethical practices.

OHSU, a public body, put a price tag of more than $150,000 on the public records request (the request was later valued at about $12,000). After a five-year court battle, the Oregon Court of Appeals slapped down OHSU’s fee as excessive and ordered it to release the records.

In fact, the case informed some of the fees section of the “Attorney General’s Public Records and Meetings Manual” (the bible of Oregon public records hounds), stating that the AG has the authority to decide whether an agency is using a fee to “constructively deny the request, rather than to recoup the agency’s actual costs.”

Fines of this size are “going to prevent the public from having that information,” Bahr says.

But fees need not be substantial to create a barrier. Look at the case of Harbaugh and his public records request to the Oregon Board of Psychologist Examiners (OBPE) after UO staff psychologist Shelly Kerr copied for UO attorneys the confidential records of the victim of an alleged gang rape by UO basketball players in 2014.

When OBPE director Charles Hill declared a closed hearing for the UO’s appeal of OBPE’s $5,000 fine of Kerr for misconduct, Harbaugh requested to see the board’s “Notice of Rights and Procedures” that gave Hill the authority to close such a hearing to the public.

Harbaugh says OBPE ignored his request for weeks and then came back to him with a fee of $2.75 for the release of documents. Harbaugh calls this a transparent delay tactic, and the AG’s office agreed, writing an order for the fee to be waived, warning OBPE about such methods in the future and charging OBPE $500 for putting the Attorney General’s office in the position of having to write such an order.

Harbaugh sounded off on this case to Rosenblum and Kron at the recent task force public hearing in Eugene May 9: “This was a transparent case of a state agency using fees not to collect revenue in any meaningful sense, not to offset the cost of preparing documents, but simply to delay the release of records that would be embarrassing to them.”

[Above:UO economics professor, and author of the UO Matters blog, Bill Harbaugh at the public records task force hearing May 9 with former Lincoln County District Attorney Rob Bovett, Attorney General counsel Michael Kron and Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum]

Rosenblum says, across the board, fees should be affordable and more uniform. But don’t expect changes any time soon.

“That is actually our third priority,” she says. “We made more progress in the other two areas [deadlines, exemptions]. Costs — we may not be ready for that in this session.”

Who Wants to Know?

Bahr and Walth say that Oregon public officials systematically shut down fee waiver requests as a way to prevent potentially embarrassing or unscrupulous information from getting out.

In the spirit of OPRA, however, it is the recommended practice to waive fees if the request is deemed in the public interest. And, Bahr adds, the law as it was intended favors giving access to the media and research groups, as they help communities disseminate information.

Kron of the attorney general’s office says that, in most cases, public records requests submitted by the media are considered in the public interest.

“I think most people would agree that if a reporter is making a request for records related to a story that they’re working on to publish in the paper,” he tells EW, “that that would certainly meet the public interest.”

So, is Kesey Square in the public interest?

City Councilor George Brown of Ward 1, where Kesey Square is located, put it this way: “That’s a public piece of property that’s proposed to be privatized. It’s clear to me from the testimony I’ve heard that, overwhelmingly, people want to keep it a public space and make it nice. That’s definitely in the sphere of the public interest. You’re removing a public asset by privatizing it, plus there happens to be the deed restriction that states very clearly that it has to remain in the public domain.”

The city of Eugene, or rather its staff, disagrees.

Twice in early February 2015, EW asked the City Recorder’s Office to waive the $447.20 fee, reemphasizing that Kesey Square has consistently been in the press and part of the community discussion for months, and that EW would publish its findings from the results of the records request.

Crockett denied the paper’s request to waive the fee. Crockett cited Administrative Order No. 21-05-06 F and stated that the “City Recorder’s Office considers whether doing so is in the public interest because making the requested record available primarily benefits the general public. Based on this criterion, the City Recorder’s Office has determined that a fee waiver will not be granted.”

When pressed further about the public interest requirements needed to meet a fee waiver, Crockett did not respond.

“In Oregon it’s almost universal that public bodies will deny fee waiver requests,” Bahr says. “It’s just the way it is, and it’s horrible.”

Bahr, in fact, says EW’s written request was not “bombproof” enough to elicit a fee waiver.

“I will spend 90 percent of my effort drafting the fee waiver,” he says. Bahr explains while this is in no way what the law intended, Oregon’s public agencies have put a high burden of proof on the requester.

And as both Bahr and Walth have pointed out, the discretion to waive the fee is always up to the agency. If a fee waiver is denied, the requester can appeal to the Lane County District Attorney’s Office (for municipal and county agencies) or the attorney general at the Oregon Department of Justice (for state agencies).

Lane County DA Patty Perlow has been handling appeals to public record and fee waiver denials since she became a chief deputy in the DA’s office in 2009. Perlow says that, in the DA’s office, appeal decisions are based on “looking at history” and “legal precedents.”

Perlow says Oregon public records law is due for reform. “I would like better guidelines on fees,” she tells EW. And her advice for those seaking to appeal denials?

“If the appeal is just ‘I didn’t get my records fast enough,’ it probably will not result in us getting the records any faster for that person; the appeal process will take probably the same amount of time to get the records,” she says, and pauses before continuing, “although sometimes having us call has an impact on turnaround time.”

A ‘Reasonable’ Deadline

“The main thing is getting some damn deadlines that have teeth,” Bahr says, adding that “there is no deadline. This is one of the great failings of the Oregon Public Records Act.”

EW made its initial public records request for emails to the city of Eugene Jan. 27, 2016. After requests failed to get the fee waived, EW submitted a check for $447.20 to the city on Feb. 25.

It is now the last week of May 2016 and the request for emails has yet to be fulfilled completely — three months after the paper paid for it.

Crockett instructed us to check back with the city in a week for the status of the request. After a week, Crockett responded via email: “We are still processing this.”

At the two-week mark, March 11, EW checked in again and received this response: “We are at about the halfway point at this time.”

At the four-week mark, March 28, we asked for an estimated time of arrival, and Crockett wrote back on March 30: “It’s a large request and we are still plugging away at it.”

The first part of EW’s public records request was not available until April 29. The city has technically done nothing wrong here, because Oregon allows public officials to complete requests in what they deem a “reasonable” amount of time.

As identified in the Kroger Report, 33 states, as well as D.C., have established deadlines; Vermont has the shortest deadline with two days and Pennsylvania has the longest with 35 calendar days.

It took the city of Eugene 64 days to make the first portion of the EW’s public records request available. As of May 26, 96 days have passed and the request is not complete.

“Oral and written testimony indicates that Oregonians believe the lack of firm deadlines allow government officials to intentionally delay releasing embarrassing documents,” the Kroger Report says.

“I think most journalists would agree that a reasonable deadline is a good idea,” Walth says. “It’s an important incentive that the law now lacks.”

While the AG’s office is examining deadlines, Rosenblum counters that deadlines may impose unrealistic standards and have inadvertent effects.

“There’s different viewpoints about that,” she says. “Having a deadline would mean that the agency could wait longer than they otherwise would.”

In other words, an agency with a deadline of 35 calendar days could wait until the 35th day to produce public records, instead of producing them as soon as they are ready.

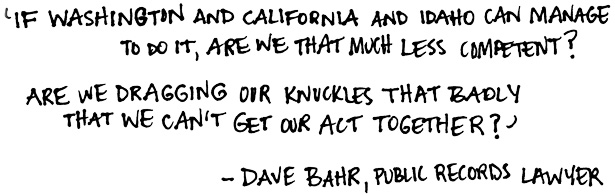

Bahr shrugs off this argument, adding that he’d be satisfied with any deadline that is a month or less.

“If Washington and California and Idaho can manage to do it, are we that much less competent?” he asks. “Are we dragging our knuckles that badly that we can’t get our act together?”

Still Waiting

The first part of EW’s public records request was made available April 29 on a burned CD, but there was something odd about it. According to the city, this CD included the “majority” of the request, yet the emails on the CD were already accessible for free on the public computer (which allows members of the public to read the public emails of the mayor, City Council and city manager) in the city manager’s office.

EW knows this because we had already accessed the majority of these emails.

When asked about this — that the city had charged a fee for emails that were freely available — neither Crockett or senior City Recorder Beth Forrest responded.

On May 10, Crockett alerted the Weekly that the remainder of the request was ready for pickup, but then another strange thing happened: It was brought to EW’s attention that the city had changed the nature of EW’s request.

Councilor George Brown forwarded EW an email from Crockett that he’d originally sent to city councilors and the mayor in relation to our request. Everything described in Crockett’s email was verbatim to EW’s request, except one aspect had been tweaked: Crockett had changed the search term, “Rowell Brokaw Architects,” to “Rowell Brokaw Architects as it pertains to Kesey.”

This may not seem like a red flag, but consider this example: Trying Googling “Richard Nixon.” Now try “Richard Nixon Watergate.” The first search offers 55-million-plus hits; the second only half a million.

While Bahr says cases like this usually stem from incompetence rather than malfeasance, public agencies cannot narrow the parameters of a public records request without consent from the requester.

The city has yet to respond as to why it narrowed the parameters of EW’s public record request without permission or notification. Until the search is done with the correct terms, the request remains incomplete.

May the Task Force Be With You

Walth, Bahr and Harbaugh attended the task force’s May 9 public hearing hosted by Rosenblum and Kron in one of the shiny new rooms at the UO’s renovated School of Journalism and Communication.

Also in attendance were former Lincoln County District Attorney Rob Bovett (he now sits on the task force), long-time UO journalism instructor Rebecca Force; former dean of the SOJC-turned “Faculty Athletic Representative” Tim Gleason (who has been a frequent subject of Harbaugh’s ire on UO Matters for lacking transparency); and a handful of lawyers and students.

One speaker said it was more appropriate to call OPRA the “Oregon Official Secrets Act.”

Walth sat quietly taking notes. As did Gleason. Bahr and Harbaugh both gave testimony to Rosenblum, Kron and Bovett.

Bahr took the podium twice. He spoke of the need for enforceable deadlines, comparing Oregon to Washington state, which has a deadline of five days. He explained how, in his professional experience, he sees that local media rarely get fee waivers granted in places like Lane County, the city of Eugene and University of Oregon.

[Above: Public Records lawer Dave Bahr at the public records task force hearing May 9 with former Lincoln County District Attorney Rob Bovett, Attorney General counsel Michael Kron and Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum]

“That system is broken. It’s just broken,” Bahr said.

Harbaugh challenged Rosenblum, asking why the AG office hasn’t written stronger opinions in favor of disclosure of public records in disputes, as Frohnmayer was known for doing.

“That would be a simple change,” Harbaugh said to Rosenblum. “It would not take an act of the Legislature, which we all know is just as likely to lead to changes that will decrease the amount of transparency.”

He added: “That’s within your power to do right now.”

Rosenblum responded: “I wouldn’t be doing this — inviting you all here, spending all the time and the resources, and taking up others’ time on the task force — if I didn’t generally want to take a deep dive into this subject matter.”

To conclude the meeting, Rosenblum stated: “The focus and the approach we’re taking has a very good chance of excellent results when we get to the point to where we have some legislative concepts, which we are going to be developing, and there’s even a deadline on that.”

Rosenblum will take the information gathered from the task force and create a legislative concept, or a framework for a bill, which will eventually be introduced to Legislature in 2017. The concept is due in June.

After the task force, Walth said he was optimistic about the potential for reform under Rosenblum.

Dave Bahr said he’s hopeful, but uncertain about change.

“I thought that particularly Michael [Kron] was attentive. I thought the attorney general was much more interactive than I expected,” Bahr said. “I get the sense that they’re trying to do something.”

He adds, however, that he expects there will be strong pushback from the legislature and public agencies.

Harbaugh remains cynical. He calls Rosenblum’s efforts a redo. “It’s so disillusioning to see a new attorney general falling back on the same old stunt,” Harbaugh says.

The Heat is On

In an earlier discussion with Walth, EW asked what an average citizen searching for public information could do in the face of this OPRA juggernaut.

“My advice is to ask lots and lots of questions before you make your request; try to find out what’s available and how it is kept,” he said. “Keep your request as narrow and specific as possible.”

Walth added: “You have to keep the heat on. You have to absolutely remind them day after day that they have a duty to respond.”

And as for EW’s request, we’ll keep the heat on. Tune in next time to see what one public records request reveals about Kesey Square.