A spirit of revolution stirred on the UO campus in the spring of 2007.

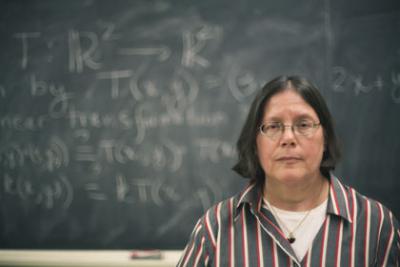

That’s when a small group of activist professors — led by math’s Marie Vitulli and political science’s Gordon Lafer — began meeting in vacant classrooms to discuss starting a faculty union.

The profs had watched with a growing sense of powerlessness for years as the university reduced their benefits, stuffed reams of cash into athletics as faculty salaries stagnated and lagged against comparable institutions, and welcomed tides of low-paid adjuncts to teach an ever-expanding student body while attrition steadily chipped away at the ranks of tenured professors. The group also had come to see the University Senate — ostensibly representing the views of faculty — as having been neutered and co-opted by the administration, leaving faculty with virtually no say in decisions at the university.

“It was just lip service from the administration,” Vitulli recalls today about administration’s response to faculty concerns. “Nothing really changed.”

Vitulli and Lafer soon realized that they had nowhere near the time and resources that would be necessary to move beyond the classroom sessions and educate and organize a large and diverse body of faculty into a union. So, toward the end of the year, Vitulli sent an email to the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), a massive union based in Washington, D.C., and asked if they would help unionize the UO faculty.

To AFT organizers, it must have felt as if their ears were burning. For most of its nearly 100-year history, the union had focused on K-12 schools, but more recently it had begun to organize higher-ed institutions. It had had success teaming with the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), which is less a union than an academic standards and practices commission, to organize faculty at the Universities of Alaska and Vermont, and ever since then the two had been looking for another major research university to jointly work with. UO was especially attractive because of its location: If they could establish a union here, it would give them a “high-research” school in the Pacific Northwest, where their presence was slight in comparison to other regions of the country. (All the public universities in the state except Oregon State now have faculty unions, but UO is the only one of those universities considered a top research institution.)

The AFT quickly hired a consulting firm to survey the campus and feel out the level of support. It determined that Eugene was a good investment (faculty union campaigns can cost upward of a million dollars, though the AFT would not confirm what they have spent here), and sent reps to talk with Vitulli and Lafer. By 2008, the AFT and AAUP had signed a contract to jointly organize the UO faculty into a collective bargaining unit they named United Academics of the University of Oregon. Not long after, AFT organizer Dennis Ziemer flew in and rented out office space above the Red Rooster Barber Shop on East 13th. Organizers set up huge charts to track support in schools and departments across campus, and the fledgling union began to plot its strategy to win over the critical mass of supporters (50 percent of the proposed bargaining unit, plus one) needed to be certified by the state Employment Relations Board and set up the first collective bargaining agreement between faculty and administration in the university’s 130-year history.

By 2007, there had already been a number of attempts to get a faculty union going here, but all those efforts had flared out. Grad students had unionized, as had classified employees — but any union sentiment among professors remained vague and unformed, abstract. So what was different this time? For one thing, the march of history.

In 1935, the Wagner Act protected labor’s right to collectively bargain with management, but for many years unions were largely a blue-collar phenomenon, the province of factory hands, electricians, plumbers, coal miners — folks who got their hands dirty at work and whose backs and knees went out too young. Elementary and high school teachers, who often worked under factory-like conditions, had formed unions, but the Ivy Towers long remained apart, immune. Professors studied and chronicled the labor movement, but it didn’t seem to relate to their situation and working conditions. Compared with other workers, professors were doing fine — salaries far higher than national averages, reasonable working hours, comfortable offices, relatively secure positions and an opportunity to pursue their passion for research. Having scored a gig like that, who would want to hazard a clash with management?

During the 1970s, however, a rash of teachers’ unions at community colleges set a precedent and profs began thinking — could things be better? Anti-union legislation in many states hindered — and continues to hinder — unionizing at private colleges, but most public universities have always enjoyed the legal right to collectively bargain. And conditions had changed on campuses nationwide. Administrations had begun hiring adjuncts at temp-worker wages to teach classes normally helmed by tenured professors, and had been focusing more on “branding” the university to sell it to prospective students. By the time the UO drive got going, there had been for many years a reaction among university faculty nationwide against what was seen as the corporatization of higher-education, a bottom-line approach that eroded the university’s mission of cultivating novel ideas through research, promoting freedom of investigation and thought and offering the highest quality education possible.

“Administrations had begun to treat the university and the delivery of classes as something coming off a production line that can be met at the lowest cost possible,” sociology professor Michael Dreiling says. “By depending on adjuncts — people paid $4,000 a class for a 10-week term, busting their ass, with no guarantee they’ll be there the next term — the environment the students are learning in is degraded.”

Still, in Eugene, the effort didn’t exactly get off to a sprinter’s start. Faculty involved in those early years say that AFT’s Ziemer seemed out of touch with the nuances of higher education, had a hard time understanding the different categories of faculty, and overall didn’t inspire confidence in the ranks of faculty activists. As Ziemer and faculty were trying with little success to iron out the kinks and personality clashes, the Provost’s office had begun sending out memos to faculty “educating” them on the unionization process. In one memo dated Nov. 17, 2009, Provost Jim Bean cautioned faculty to “Please read carefully anything you are asked to sign … as you may be giving up your right to vote and committing yourself to inclusion in the union.” They banned union activists from using campus email to communicate to their fellow professors about the union, according to Vitulli. They also built an “informational” website for faculty to visit, countering United Academics’ website. Meanwhile, pro-union profs were fanning out across campus to introduce the idea of a union to other profs. Political science professor Gerald Berk was one of those charged with rapping on office doors, behind which he found a mixture of support and caution.

“It was all over the map,” he recalls. “One person said to me, ‘I trust the administration to make good decisions, and I know union-management relationships tend to be adversarial, and I don’t think it would be good for the university as a whole.’ To which my response was, ‘Tell me about those good decisions. If they’re good decisions, why are we one-third tenure-track, two-thirds contingent faculty, and why are we in salary scale on the bottom of all our comparator institutions?’”

In a state with a median household income of $49,000, you might risk an aneurysm trying to coax a tear for a professor pulling in more than $80,000 a year (UO profs’ average), but it’s important to place it in perspective: Of the 60 member institutions in the Association of American Universities, a grouping of elite research universities, the UO ranks dead last in salary. There are many who feel that this makes it tough for the university to retain the best and the brightest, thereby undermining its stated mission to provide the highest-quality education possible to students in Oregon.

“We hire good people and we lose them really fast,” says history professor David Luebke. “Other universities know Oregon has lots of good talent for the plucking.”

By the summer of 2010, nearly three years since the effort began in earnest, United Academics still had not initiated the card-check phase that would lead to its certification, the amassing of a critical number of supporters that would make the union a reality. The AFT removed Ziemer and brought in Yonna Carroll, and the new blood seemed to invigorate the effort. Perhaps fittingly, the Oregon State Board of Education decision to terminate the contract of popular president Richard Lariviere, in part for giving faculty and administrators raises against the wishes of the state’s governor, in November 2011, may have swelled activist sentiment and nudged the union into existence. At the very least, it was a symbolic moment.

“It reaffirmed to many of us that the idea of faculty governance is mythical, that we really didn’t have a say in the direction of the university,” Dreiling says. “He was working to try and find some solutions, to rectify some of the holes in the [UO] Constitution, to try and deal with the trends in employment relationships and salary. So this was a real look at how power works in the university system. We realized we didn’t even have a tug on the reins.”

“I think we were all still getting to know him a little bit,” says Deborah Olson, an instructor in special education. “But everybody felt he was fighting for a vision for the university. He just stuck his neck out one too many times.”

Coincidence or not, the card check drive finally began less than two months after the Lariviere’s contract termination, on Jan. 9 of this year, with the School of Law — firmly anti-union — exempted from the vote. The union had 90 days from getting the first signature to filing for certification. On March 13 it sent 1,837 signed union cards to the state Employment Relations Board. As the board was counting the votes, it came out that the administration had hired anti-union lawyers to try and squash the union effort, but by that time it was a fait accompli. On April 27, the union was formally certified. The work to maintain a stable union is not nearly done. If the faculty activists are not able to hammer out a proposal soon, the entire effort could fall apart. The AAUP just opened a Pacific Northwest office in Olympia, Wash., in large part to have someone on the ground to support the newborn UO union.

Divisions remain among tenured professors, some of whom feel that with a union membership disproportionately weighted with adjuncts (at the time of certification, only 521 of the 1,832 union members were tenure-track faculty) the specific concerns of tenured faculty will not be adequately promoted. Art history professor Jeff Hurwit, who voiced his anti-union sentiment at meetings prior to certification, is blunt:

“Somebody who teaches a yoga class in the fall will have an equal vote to a tenured full professor who teaches two classes and a scientist who might bring in millions of dollars from outside grants,” he says. “That strikes me as odd.”

Union pushers, as might be expected, have less a Beatles-breakup, more a Peter-Paul-and-Mary-linking-arms view of the prospects of an inclusive union.

“I work with non-tenure-track people all the time,” Luebke says, “and they are cognizant of the needs of the tenure faculty. I know our place in the university differs from theirs and vice versa, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that because interests are diverse, they are antagonistic.”

For economics professor Bill Harbaugh, the success of the union drive was an outgrowth of a pattern of questionable spending practices by the administration and a necessary corrective to what has been a top-down power structure.

“In theory our administrators are supposed to work with us to make this a good university,” he says. “But in practice they don’t listen, and they’ve set it up so that we can’t have anything effective to say. The university still does not have a plausible plan for how it’s going to spend its money between undergrad education, research and graduate education. The administration has failed in its responsibility to develop a plan for the university’s future and a budget for the future. They’ve been spending students’ tuition money on a raft of pet projects incidental to our mission.”

Howard Bunsis, AAUP’s collective bargaining chair, recently did an analysis of the UO’s financial condition and would agree.

“Despite what you hear, they have strong reserves and a strong annual operating cash flow,” he says. The only thing wrong with UO financial situation is their priorities. They spend too much on administration and not enough on the core academic mission.”

It’s hard to hear the word union without your thoughts going to … STRIKE! and a faculty strike could indeed have a devastating effect on the university. In 1990, the faculty at Temple University in Philadelphia walked out for 29 days, a time during which more than 1,800 students withdrew from the university. While union activists scoff at the possibility, even if a no-strike clause is included in the looming agreement, it is really a misnomer — if the union decided the administration wasn’t honoring the agreement, it would be within their rights to walk out. The prospect of a strike is the big gun unions have in establishing leverage.

“I’m concerned that should there not be a meeting of the minds between the administration and the union, the only recourse will be a strike, and that will harm our students,” Hurwit says.

Marie Vitulli, who, along with Lafer, started the movement, dropped out for health reasons during the Ziemer phase and never re-entered the fray. She observed the union’s certification from the outside but has never lost her emotional investment in the process.

“I really hope that when the contract is negotiated positive changes will happen,” she says. “A lot of things have been done so unevenly and so secretly for so long; it would be really nice if that changes.”

As this story went to press, union committees were still working on their first proposal to present to the UO administration, which did not respond to requests for comment.