The Northwest is a hairy place. For folks raised in these parts, and especially in the boonies, the world was all hair — uncles with big bushy beards, deadheads, tangle-haired hippies and yippies, the swinging tresses of grunge rockers, bears, beavers, not to mention the fuzzy moss that spreads like kudzu on every damp surface. Here, where the forests reign supreme, we like to let our hair down. Keeps us warm. Sends a message.

Part and parcel of that literal hairy-ness is the history and mythology we inherit. The pantheon of legends comprising our folklore is peopled by real and fictional icons as hirsute as Samson and bearded as billy goats: From the stubble-chinned trappers and shaggy settlers of yesteryear, from Paul Bunyan to John Whiteaker, Oregon’s first governor, right on up to present day hipsters sporting retro-porn mustaches and bushy sideburns, our life west of the Cascades is largely about hair, and lots of it.

Enlarge

Autumn Williams speaks to the Sasquatch crowd at LCC.

Photo by Todd Cooper

Few things better epitomize the Great Hairy Northwest than the bigfoot legend — that super tall, reportedly stinky and mysterious ape-like creature of the woods, allegedly seen and allegedly heard and allegedly photographed and filmed and tape-recorded hundreds of times, yet never once captured. Never definitively proven to exist. When it comes to sasquatch, there is no corpus delicti — no body, no fossils — and for that reason, among others, the thing is lumped in with other such paranormal phenomena as the Loch Ness Monster, flying saucers, alien abductions and people who see dead people.

Bigfoot, then, is our particular contribution to the trove of urban legend, though the sasquatch couldn’t be less urban. And, for some people, he ain’t no legend, neither. He’s as real as you or me. It’s just that there’s something a little, well, elusive and dodgy about bigfoot. Like an electron or Snuffleupagus, the harder you look, the less likely you are to find it.

According to the Oregon Bigfoot web site, there have been 1,248 bigfoot sightings in Oregon, 76 of those in Lane County. Neighboring Linn and Douglas counties notch 28 and 37 sightings, respectively, so we’re sort of a hotbed of sasquatch activity. That considered, it’s only right that a bunch of bigfoot people converged at Lane Community College this past weekend, coming together like Pentecostal tent revivalists for the first-ever Oregon Sasquatch Symposium on June 19-20. The two-day bigfoot bash, which was attended by more than 200 people, featured presentations by witnesses, researchers, tenured professors, one high school science teacher and a few big-time bigfoot celebrities.

OSS organizer Toby Johnson hasn’t seen a sasquatch first hand, but he is a BF believer through-and-through. This wasn’t always so. Five years ago, he and his son found what Johnson calls “a large human footprint” during an early morning hike around Thurston, though even then he wasn’t convinced he’d stumbled upon anything special. “I was used to seeing bear tracks in that area,” he said. “It just looked like it was a hoax.”

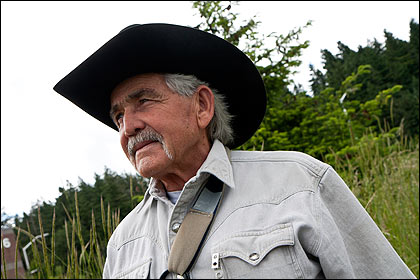

Enlarge

Photo by Trask Bedortha

Nonetheless, Johnson snapped a photo of the print and began “shopping it around to people in the community,” and things began to change. To his surprise, Johnson discovered that the Eugene area is teeming with bigfoot witnesses, though many of the people he spoke with were unwilling to go public with their stories. “For whatever reason, people don’t want to be associated out and out,” Johnson said, giving examples of witness “backlash” than can run from ostracizing and stigmatizing to the breaking up of families and workers getting fired “for sticking to their story,” he said.

Because of this, the symposium partly served as a sasquatch support group, albeit one where the therapeutic model is reversed — instead of opening up and sharing your problems, you’re simply sharing what you consider to be a healthy and indisputable truth. “Right around us there are little small miracles,” Johnson said, adding that one of his motivations in putting together the symposium was to provide “a safe environment for two or three days to talk about that weird thing that happened in the woods.”

A confederacy of bigfooters

Every night I fall asleep listening to Coast to Coast, the widely syndicated radio show that plants its flag in the shifting sands of paranormal phenomena. The listeners who call to gab with host George Nory fill the airwaves with a cross-section of belief’s outermost fringe — alien abductees and Flat Earthers, time trippers and Nostradamus fanatics, along with people who have seen flying saucers, ghosts, demons, little green men and, yes, bigfoot. I’ve always pictured the generic caller as looking like a backcountry cross between Ted Nugent and Zippy the Pinhead, and paranoid to the point of psychosis. It’s a grossly unfair portrait, I know, but there it is.

And I’ll admit that it was just this species of lunatic zealot I expected to be attending the Oregon Sasquatch Symposium. I couldn’t have been more wrong. There was nothing weird or offbeat about the people at the symposium, nor was there anything discernible in the way of gender, age, class, fashion or any other outward indicator that might describe the average symposium-goer — nothing, that is, save a rapt collective attention to the matter at hand. These folks emanated that unmistakable aura of people who know exactly why they are where they are. To a person, they were polite, attentive, responsive and knowledgeable.

Enlarge

The symposium started off with a bang. Autumn Williams, an Oregon native and daughter of bigfoot witness and symposium speaker Sali Shepard-Wolford, was a childhood sasquatch witness as was her mother, and at 16 began doing field research. She has appeared on television, including a stint hosting Mysterious Encounters, and she also heads up the Oregon Bigfoot organization. Her specialty is habituators or what she’s dubbed “long-term witnesses,” which are people who experience ongoing sasquatch encounters in the vicinity of their homes. Basically, Williams — with her striking good looks and the sharp, angular features that telegraph an intimidating don’t-mess-with-me disposition — is about as close as the bigfoot movement gets to having its own superstar.

Big feet, big johnson

Williams is an engaging speaker whose gestures and vocal style, at times, border on the theatrical. She understands how to construct a strong narrative and she also knows that when it comes to bigfoot the best offense is a good defense. This means she’s dismissive of non-believers, contemptuous of mainstream media, and distrustful of governmental and scientific agencies with their driving need for forensic evidence. “If you found a body tomorrow,” she said, “the government’s going to go, ‘Thank you very much, that’s a weird specimen.’”

Williams spent a good deal of time talking about a pseudonymous witness she called Mike, a “redneck” bulldozer driver from Florida, who claims to have developed close ties to a sasquatch he calls Enoch. Williams’ relationship with Mike appears to have had a profound, almost life-altering impact on her. “I felt like somebody had handed me the Holy Grail of sasquatch research,” she said of hearing Mike’s story.

Williams attested that Mike was an “incredibly credible” witness whose stories were “detailed” and “intense” and never once changed despite several retellings. If it’s that the devil is in the details, and so is the believability of any good yarn. And, as related by Williams, Mike shared some lovely, offbeat and wonderfully colloquial observations about “skunk apes,” which is what he calls sasquatch.

Sasquatch, Mike said, will eat just about anything, but they particularly like turtles, which they crack open and slurp “like we eat oysters on the half shell.”

“When he takes a crap, he squats down and lets fly.”

“Skunk ape farts are in a class all by itself.”

And, regarding males, Mike has this to say: “Big feet, big johnson,” meaning a horse ain’t got nothing on a squatch, though “with all the hair you can’t see it.”

According to Mike, skunk ape eyes look like “the inside of a Tootsie Pop,” their eyebrows are bushy “like Andy Rooney,” their skin color is “like a Pakistani.” They smell “like a wet, musky garbage dump,” and their mustaches grow right out of their nostrils.

Williams’ bigfoot presentation, over time, took on a distinct utopian vibe, one of rosy romantic primitivism. The underlying message of her story was that the bigfoot — community oriented, nonmaterialistic, free of artifice and, overall, purely pure as nature itself — lives a simpler, less encumbered and more peaceful way of life than human beings. In fact, it is actually us, with our alienating cities and glitzy consumer goods and fear of boredom and, as Williams put it, our constructed selves that “change on a daily basis with fads,” who must learn from the skunk apes. “We’re so far removed from what we were,” Williams said.

Enlarge

Once upon a time

To come clean personally about this bigfoot thing, I’ll put it like this: I don’t recall believing in Santa Claus even when I was a wee lad, and deep in my guts I’ve always suspected that we create gods in our image rather than visa versa, so it’s not likely you’ll convince me there are big hairy hominids thumping around the forests and we haven’t unearthed a single fossilized metacarpal. Call me a cautiously agnostic positivist, I suppose.

Bigfoot, by the way, is a cryptid (roughly, a “hidden animal”), and the study of bigfoot falls under the category of cryptozoology. Most mainstream biologists consider cryptozoology a pseudoscience. Accusing a cryptozoologist of pseudoscience is like telling a Baptist that Jesus is just a fairy tale. Over the years there have been a handful of mainstream scientist and tenured academics — including anthropologist Carleton Coon, primatologist Jane Goodall and symposium speaker zoologist Jeff Meldrum — who have staked their reputations on the reality of sasquatch, or at least saying, like Goodall, that it sure would be cool if bigfoot is real.

I’ve interviewed quite a few people recently who seemed determined to at least get me to entertain that possibility of bigfoot’s existence. I’ve been handed stacks of research papers, directed to a numerous web sites and passed a pile of CD recordings. I’m no scientist, but as far as I can tell a good portion of this research hardly qualifies as scientifically rigorous, and the prose is often riddled with typos and grammatical boners. Not exactly the stuff to inspire confidence.

A lot of amateur sasquatch research employs a forced, mangled scientific jargon that sounds silly, and there are conclusions drawn that make a Swiss cheese of logic. And the more touchy-feely bigfoot writing heaps on the nativist hoo-haw and New Age fluff like so much whipped cream spooned atop the honky appropriation of indigenous myth.

That said, it’s just as difficult to prove, scientifically speaking, the reality of burning bushes, parted seas, 40-day floods and a six-day work week where God cooked up heaven and earth, yet hoards of people continue to believe these things heart and soul. As both legend and contested reality, the real source of bigfoot’s appeal, like the source of the Bible’s appeal, is anecdotal — as a fable filled with wonder, suspense and local color, all ringed with a halo of otherworldliness.

Dave Rodriguez, who spoke at the symposium, tells one hell of a sasquatch story. A California native who moved to Oregon in the early ’80s, Rodriquez, 52, said his first sasquatch encounter occurred in 1977, when he and a buddy were driving home to Yosemite late one night. With his friend asleep in the passenger seat, Rodriguez was steering his pickup around a corner when, all of a sudden, “here’s an eight-foot hairy creature that had stopped just off the hill, right in front of me. I’m looking right into his eyes when he looks down at me.”

Skidding to a stop, Rodriguez was able to observe the monster. “I’m taking in every hair on his body, looking at every detail … the palms of his hands, his eyes, his nose.” He described the creature as extremely powerful looking. “They’re nothing but muscle,” Rodriguez explained. In the end, he and his friend agreed not to tell anyone about what happened. “They’d all think we were crazy, so we just sort of kept it to ourselves,” Rodriguez said, noting this was the beginning of a self-imposed public silence he finally broke at last weekend’s symposium.

Rodriguez has had other bigfoot sightings, bit it was his third encounter, just five years ago in the Cascades, that was the “biggie” — a harrowing close encounter that had him freaked and housebound for a week and a half afterward. “That one shook me,” he said. Although accompanied by his hunting dog and armed with a deer rifle, Rodriguez still didn’t feel safe. “My 30-30 felt like it was about six inches long,” Rodriguez says of his rifle, adding that in terms of ballistics, “there’s no match” for a sasquatch.

“I was able to keep calm,” he said of having to pass within feet of the beast in order to return to his truck. At one point, Rodriguez and the bigfoot “both turned toward each other, breathing heavy,” and he caught a whiff of the creature’s odor. “I got a really good, strong smell of him,” Rodriguez explained, discounting widespread claims about the horrible stench of a sasquatch. “He smelled just like a wet elk. It wasn’t all smelly or sewagey.”

Perhaps the most interesting part of Rodriguez’s story is the epilogue: After keeping quiet for years, the concerns that ultimately compelled him to go public about bigfoot were ecological and humane. Basically, Rodriquez wants you and me and everyone to believe in sasquatch so we can get busy protecting the creatures and their habitat. “There needs to be some education,” he said, which for him means moving beyond the “mindset” that they don’t exist. “Whether they’re endangered or not, that’s another question,” he said. “But they need to be treated as a sentient being. We trash the environment and shoot up things we don’t understand. We need to respect them more, but they need to ‘exist’ before that can happen.”

Enlarge

Photo by Todd Cooper

Movies, myths and the bigfoot fetish

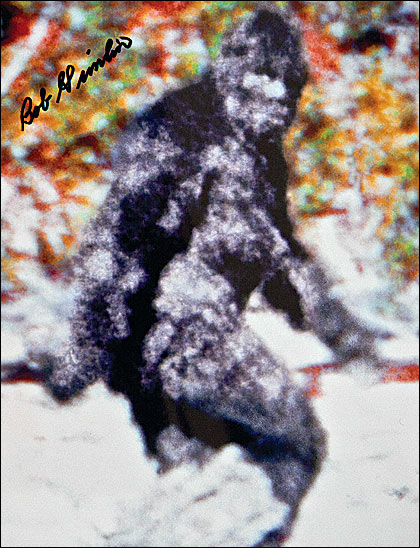

By far the most famous sasquatch footage is the sequence captured in the region of Bluff Creek, California (some say staged) with a 16-millimeter camera in 1967 by Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin. This is the Zapruder film of bigfoot footage, with a history just as long, tangled and topsy-turvy with intrigue. The Patterson/Gimlin film has been endlessly played and analyzed and and dissected, frame by grainy frame. And, whether hoax or cinematic proof, the jumpy footage is seriously creepy, especially that moment (the fabled Frame 352) when bigfoot turns and looks into the camera.

So let me confess that shaking hands with Robert Gimlin at the Oregon Sasquatch Symposium was just as thrilling as the times I met Spaulding Gray or Alex Chilton. I can’t believe I just said that, but I think my excitement had something to do with being a Northwest boy who had the crap scared out of him repeatedly by that footage. Nearly every culture on the planet has ancestral stories of super-sized human-like monsters roaming the earth, but sasquatch is a distinctly Northwest phenomenon, as much a part of our culture as rain, Raymond Carver, good pot and red delicious apples.

And, just like Nike or Microsoft, sasquatch has gone global, becoming a worldwide superstar of the supernatural. Bigfoot battled the Six Million Dollar Man, for Pete’s sake, and also took the lead alongside John Lithgow in Harry & the Hendersons. He’s the hero of a current kids’ cartoon, and I would argue that sasquatch inspired the wookie Chewbacca in Star Wars. Bigfoot was even mentioned in the most recent episode of HBO’s vampire series True Blood. Sure, sasquatch sightings have been reported down South and on the East Coast, but I would chalk that up to nothing more than bigfoot envy. Let them name their Hampton hairballs and Baton Rouge rampagers something else. Sasquatch is ours.

Leaping with faith, looking with logic

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion wrote. At the Oregon Sasquatch Symposium, people told stories in order to prove that something else lives despite mountains of doubt and a lack of palpable proof, which is something akin to the religious impulse compelling converts to proselytize. Some symposium speakers trotted out science, some offered up anecdotal evidence while yet others simply presented the defiant example of their personal belief, which was a “leap of faith” into the contested realm of all things paranormal. This tension between science and storytelling begs the question: Is there a hierarchy or status among all these inexplicable, unsolved tales we continue to talk about and debate? Is the possibility of bigfoot’s existence, by its very nature, somehow more believable than, say, the idea of being abducted by aliens? Somehow, I think there is a difference, not of degree but of kind. Or, put another way, if I happened upon a sasquatch in the woods, I’d be far less shocked than if I were to discover I had a double living an alternate life in another dimension.

There were times during the symposium — like when “Mike” phoned Autumn Williams, a little too conveniently, right in the middle of her lecture — that pushed the envelope of credibility. Mostly, however, the presentations I attended were interesting, entertaining, earnest and unexpectedly full of diverse or conflicting opinions. Organizer Toby Johnson did a superb job enlisting an array of speakers and presenters who proved unencumbered by any single strain of bigfoot orthodoxy.

My mind was changed not one iota about the existence of bigfoot, which is not to say my mind wasn’t changed at all. It’s possible to gain respect for someone’s views without believing the things they so devoutly believe. So I must say that, after hanging out at the Oregon Sasquatch Symposium, and as odd and disconcerting as it is to say, I think I might have been the person most drastically affected by the proceedings. I’m not sure what to think anymore, because either there’s one serious mass delusion going on, or bigfoot exists, or those people were the best liars I’ve ever encountered.