Earth Day 2010

Let it Flow Restoring Green Island

Prickly Project Wrestling thorn vines in the nude t’aint for sissies

Make Way for Turtles Can kids get the UO to help the Millrace?

Maintaining a Beautiful Butte The key is to stay on the trail

Let it Flow

Restoring Green Island

By Camilla Mortensen

Restoration is not for the faint of heart, not at McKenzie River Trust’s Green Island. When Joe Moll and the staff of MRT talk about restoration, they get gleeful about falling trees, bulldozers and sheets of water flowing across fields and through long unused channels.

|

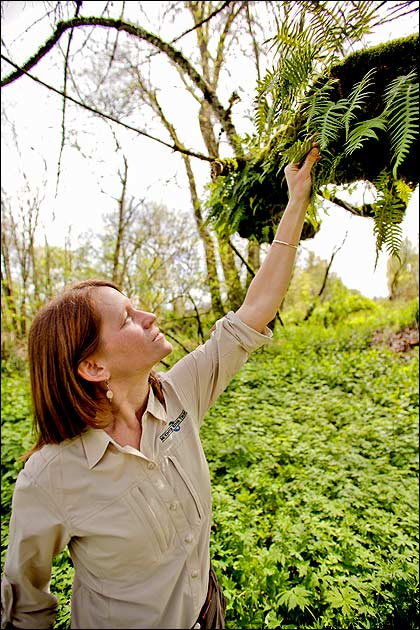

| Brandi Ferguson examines ferns on Green Island. Photo: Trask Bedortha. |

|

| Young ponderosa pines take root on the island. Photo by Trask Bedortha. |

“We’re probably the only group that gets excited to lose land to the river,” says Chris Vogel, the project manager of this venture that is MRT’s pride and joy.

Green Island isn’t really an island these days, though it was before the river changed its course more than 40 years ago. The area is about 1,000 acres made up of one large chunk of land, several smaller islands, river channels, farmland and a prime location at a biodiversity hotspot — the confluence of the McKenzie and Willamette Rivers near Coburg.

Looking out over the acres of farmland, newly planted trees and farm roads, the trick is not to see what is there, but what will be. Some of Green Island is still being farmed in accordance with an agreement made when MRT acquired the land. But year by year, more acres are being divested of crops in some areas and invasive blackberries and Scots broom in others and slowly planted with trees, grasses and understory plants, thanks to MRT and its volunteers from kids to retirees to the Northwest Youth Corps.

The once groomed farm fields are gradually becoming wetlands, grasslands and forests. Vogel says that in spots where MRT has phased out the farming, native lupine and goldenrod have popped up, despite having been plowed under and sprayed out for years. There’s still some native seedbank, he says, lurking under the soil after 70 years of farming.

Old flood control structures are being removed to let the river, in this one spot at least, leave the unnatural waterway that development has squashed it into and let it meander and flow naturally across the land and into its old channels. Vogel compares the current removal of a levee to the removal of small dam. “It has the potential to be the removal of one of the largest obstacles to the natural floodplain process in the basin,” he says.

“It represents a really long term vision for the site,” Moll says. “People look at restoration projects in a time bound sense,” but really, he says, “the restoration process goes on for generations.”

Standing near the spot where several years ago the river washed away 12 acres of the island, Moll grins while he eyes the missing chunk of land, with a tree teetering on the edge of the bank, and says, “Ultimately what we want is a system where monster trees are tipping and falling into the river.”

MRT is planting trees to watch them grow and thinking about some days, years from now, when those trees will fall in the river and provide habitat for salmon and the caddis and May flies that river species feed on.

These newly hatched bugs flitting around as Moll, Vogel and development director Brandi Ferguson discuss their vision for the land aren’t an annoyance. They’re a sign that MRT is succeeding in its mission to bring back the native species of all sizes and shapes that once grew, roamed, flew and swam in this area. Where anyone else might see a pile of trees in the river, the folks at MRT see “complexities.” Moll says, “That big pile out there is beautiful from a restoration perspective; for boating, you have to watch out.”

Vogel says that unfortunately someone has been motorboating up to tangles of trees in the water from Green Island downriver to Harrisburg, chainsawing and burning them to clear them from the water. “There’s a certain mentality that a clear river with no obstructions is a good river,” he says. But the tangles are what provide the food and shade salmon and native fish need to flourish. The waters around Green Island are home to Oregon chub, a federally listed minnow that is only found in the Willamette Basin, as well as spring Chinook, Western pond turtles and red-legged frogs.

Back on land, the trees MRT is planting aren’t necessarily the natives Eugeneans are used to seeing. Some of the trees are the black cottonwoods hikers normally encounter in their hikes along riparian areas. But others are trees associated with the dry east side of the Cascades near Bend — ponderosa pines.

Moll says that the Willamette Valley was once home to many of these trees that conservationists affectionately call “pondies.” But settlers logged the tall red-gold trees in the 1800s, leaving very few behind. You can’t just take a pondie seedling from Bend and replant it in Eugene, according to Moll. It can’t take the wet. The pondies being planted on Green Island are a race or strain of the tree called the Willamette Valley Ponderosa Pine that is capable of growing in the wet areas in the Willamette Valley and near waterways.

Green Island is wet. It isn’t just surrounded by the river; the waters flow underneath the island, according Moll and Vogel. When the planted pondies get a little older, time will tell what their deep taproots think of the waters of the Willamette and the McKenzie. Time too will show what happens to the river when it slowly begins to flow naturally, around, over and through Green Island.

MRT has been having a series of events all through April celebrating “The Living River.” At the Hult Center Studio 7 pm Friday, April 23, Robert Faggen will speak on Ken Kesesy and rivers. For more info on upcoming events and volunteer opportunities, go to mckenzieriver.org