The Value of Vets

Is Eugene caring for its female veteran population?

By Alexandra Notman

|

| Photo by Alexandra Notman |

|

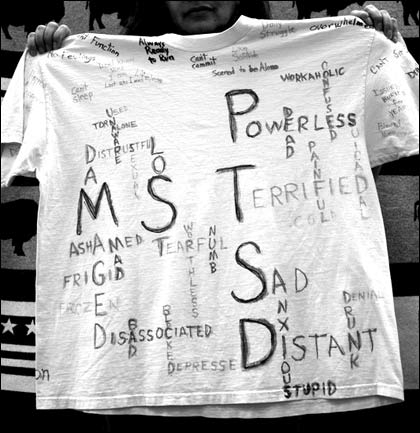

| A T-shirt voicing the pain of a victim of military sexual trauma. Photo by Alexandra Notman. |

|

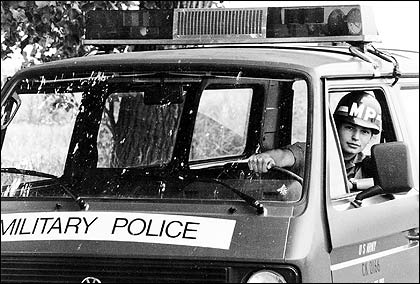

| Veterans social worker sonja fry served in the military police. Photo courtesy Sonja Fry. |

Rape. Shame. SOS. Black Hole. Self Blame. Abnormal Terror. Faceless.û

Hundreds of T-shirts howl with the painful memories of veterans who were sexually assaulted while serving. One shirt bleeds crimson paint from a red splatter over the heart and is emblazoned: øAttempted rape by my Commanding Officer.” Another T-shirts slogan wails, øSexual Assault Scars for Life.” Sonja Fry, a licensed clinical social worker with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in Eugene, pulls shirt after shirt out of a bin in her office.û

She lingers on one and smiles. øHope lets you live among the scars. I know that now,” it says. The T-shirts are part of an art therapy project she is working on with her clients at the VA Mental Health Clinic downtown.

Fry, who works mostly with female veterans, is chipping away at several projects to improve veterans postwar health care. In the past six months she has cultivated a waiting area for female veterans separate from the general waiting area, complete with a gurgling fountain, stacks of magazines, a large buffalo tapestry and a dream catcher hanging from her office nameplate.

øThey dont want to sit out there with the guys,” Fry says, waving her hand to the other side of the clinic. øThose were the perpetrators. When youre in the military, and youre a woman, and youre around men, they are all staring at you. You are always on watch.”

Fry began sexual assault counseling years ago on Native American reservations when she worked at a rural hospital in Forks, Wash. She has always gravitated toward social work. øI think its because what has happened to the Indian people,” says Fry, who is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma. øIts my own innate need to help with the oppressed.”

Now in Eugene, her focus of the past four years has been working with survivors of military sexual trauma (MST), or veterans who were raped, sexually assaulted or severely sexually harassed by fellow service members while serving in the military. Survivors may suffer from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, nightmares, isolation, suicide contemplation, gastrointestinal complications and the inability to experience healthy relationships. øIts amazing that women veterans survive after that, that they can still make it in society and be productive,” says Fry, a former military police officer and an MST survivor herself. øWell, the truth is theyre struggling.”

A study recently released from the Oregon Health & Science University titled øSelf-inflicted Death Among Women With U.S. Military Service: A Hidden Epidemic?” found that women veterans are more than twice as likely to commit suicide as their civilian counterparts. Fry reports that 22 percent of women veterans have experienced MST and the majority has experienced severe sexual harassment. A report released last October by the Oregon Legislative Task Force on Women Veterans Health Care declares that MST and domestic violence among female vets have reached dangerous rates. The majority of assailants are fellow soldiers or higher-ranking officers.û

Of the 2.5 million female veterans in the U.S., more than 25,000 female veterans live in Oregon. More than 2,000 of them use Eugenes VA facilities. These problems will likely worsen as the number of women in the military is expected to double in the next decade. Portland responded to this crisis by opening Oregons first and only female veterans clinic last fall. The VA is planning to build a new $40 million, 100,000 sq. ft. primary medical clinic in the Eugene-Springfield area by 2014, which raises the question: Will Eugenes female veterans community finally get the care it needs?

Post traumatic stress

One female veteran gave up on the VA before she ever got to meet Fry. She found herself fighting a different kind of war at home in Eugene ‹ a war for proper care. An Iraq War veteran and UO masters student, Gabriella Ramirez (not her real name), feels that the VA health care system needs to be revamped. Five years after her return from Iraq, Ramirez cannot silence the crackle of gunfire or the rumble of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). She still remembers the weight of her M16 in her hands as she juggled the steering wheel of her Humvee (øThey taught us how to do government drive-bys,” she says). She cannot forget the relentless unwanted sexual advances and intimidation, like the night when she was walking across the base to call her husband and an officer stepped out of the shadows holding an M16 and asked, øWanna fuck?” (øI guess it was sexual harassment. I guess Im afraid to say it.”) Now she cannot drive, speak publicly or develop new relationships without it causing her heart-racing anxiety. Gabriella Ramirez has PTSD.û

øI walked into the Eugene VA clinic because I thought I was going to die,” says Ramirez. øThe first thing they do is give you drugs. They gave me Trazodone, Klonopin and a waker-upper. This Trazodone. I cant even explain how strong it is ‹ like a coma. They try to make you forget the nightmares, I guess.” But Ramirez did not want to be medicated; she did not want to forget; she wanted therapy. She briefly saw a psychologist at the clinic before funding dried up and she was directed to the Eugene VA Clinic on 13th and Pearl.

Female veterans like Ramirez are the reason Fry joined the Oregon 2010 Legislative Task Force on Women Veterans Health Care. Acting as the MST subject matter expert, Fry taught the task force about her counseling experience. Made up of health care professionals, VA employees and state politicians, the task force traveled throughout the state to assess the standard of care for female veterans. One of its major findings was that VA employees are buckling under their bloated caseloads, typically higher than the 60-caseload limit recommended by the VA.û

øI will be honest with you,” Fry says, releasing a deep sigh while shuffling through papers on her desk. øRight now, I have running probably 160 caseloads.” According to the report released by the task force, that is three times higher than the number considered safe for counselors.

When counselors are overworked, their patients suffer. Ramirez knows this all too well. At the Eugene Vet Center, a clinic specializing in treating veterans who have faced combat, she sought out therapy but ran into several obstacles. First, she was allowed to make only one appointment at a time, due to the already high influx of veterans, allowing weeks to go by between sessions ‹ a less than ideal situation for someone suffering from severe depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts. Then the clinic began offering a female veterans PTSD support group. Excited, she jumped at the chance to commiserate with fellow female veterans, a cathartic release for Ramirez that helped her realize she wasnt the only woman struggling with PTSD. One day during a session, the group facilitator pulled Ramirez aside and suggested that her problems were better suited for one-on-one therapy. øI guess I went kind of deep,” says Ramirez of sharing her fears with the group. Feeling like an outcast, she stopped attending sessions. The Eugene Vet Center did not respond to a request for comment.

Gender and veterans

Oregon Sen. Laurie Monnes Anderson, also a task force member, is concerned about gender inequity in military culture. øForty years ago, there were very few women in the military. Now there is tenfold,” Anderson says. øIts been a mans world and it is not adequate at all for womens health care.” The report released by the task force outlines the unique needs of womens physical care including breast examinations, cervical cancer screening, menopause management, obstetric care, the treatment of reproductive cancers as well as mental care, especially with depression, which is found in higher rates among female veterans than male veterans. The lack of childcare resources for female veterans seeking care was also identified as problematic. øSome women dont reach out to the VA,” Anderson says. øThey feel the VA only reaches out to men.”

Ramirez didnt want to believe that women are marginalized both in the military and when they return home, but she has experienced it too many times to deny. In search of the support of the veteran community, she decided to pay her dues ($1,000) and become a lifetime member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). One night, she showed up to Eugenes VFW post at the Veterans Memorial building (aka Macs at the Vets Club) on Willamette Street for a member meeting. She was the only woman. øThere were 15 men and they all just looked at me. It was a boys club,” she says, grimacing. She sat in the back row until the end of the meeting when she decided to ask about the hats some of the veterans were wearing. øThey told me the hats were reserved for soldiers who had experienced combat,” says Ramirez, who did experience combat as a convoy driver. The group then directed Ramirez to the Ladies Auxiliary VFW, a group for wives and female family members of veterans. Insulted and out of viable options, Ramirez gave up her search for a female-friendly veteran community and now pays out-of-pocket to see a non-VA-affiliated therapist once a week. øShes my angel,” she says of her therapist.

But Fry and Anderson point out that there may be some relief for Ramirez soon, at least financially. The task force proposed 12 recommendations to the Oregon Legislature. The Oregon Senate studied these recommendations and unanimously passed a bill this spring øurging Congress to mandate the United States Department of Veterans pay for an MST treatment, even if it is provided outside of VA facilities.”û

Although Ramirez does not consider herself an MST survivor, perhaps this sets the precedent for veterans struggling with PTSD as well.û

No Eugene clinic for women vets?

øI would love to see our soldiers being cared for where they live ‹ reimbursed at the local level,” Sen. Anderson says in a phone interview. The obstacle, however, is that most veterans do not live in Portland or Roseburg, home of the only full service VA facilities in the state. Veterans like Ramirez are tired of the 90-minute drive to Roseburg to get check-ups.û

Another problem the report identifies is the lack of mental health care professionals available outside of the VA who specialize in the treatment of MST survivors and PTSD. One recommendation suggests dispatching mobile health care buses to rural areas, but that will not provide the long-term care that the VAs model of evidence-based therapy often requires, specifically cognitive processing theory and prolonged exposure therapy. The task force also emphasizes the necessity of in-patient facilities, which would not be possible with a bus. Anderson would love to see a women veterans clinic in Eugene, just like in Portland. øWe just dont know if there is going to be money. Its been a very slow process this time,” she says. The 2011 Oregon Legislative session adjourns at the end of June. øWe will know then,” Anderson says.

The report also finds that there are no protected funds for women veterans within the VA budget. The task force recommends requiring the Veterans Health Administration to fully fund the women veterans health care initiatives and mandates. By fall VA officials expect to know where the new $40 million veterans primary health care clinic will be located, The Register-Guard reported. There was no mention of allocating funds specifically to women veterans health care. However, VA Women Veterans Program Manager Marcia Hall says that a section of the new clinic is being designed with women veterans health care in mind. øThe idea that there is a different structure that is required to provide the services for womens health care is not part of the VA history,” Hall says. øWere changing that.” The female designated area of the clinic will be housed in the same building as the male designated area and there will be no in-patient beds available. There is also the question of finding enough specialized mental health care workers to fill an expected staff of 200. øDo we have room to grow and improve?” Hall asks. øAbsolutely.”

øThere are a lot of women who want to be heard,” she says, inching forward in her desk chair. øIf more people speak up maybe they will put a little more money into prevention programs, and maybe they will put more money into treating veterans.”

Whatever happens, Fry is determined to keep developing programs and building an MST awareness campaign. Last April, Fry and Hall performed the øMST Monologues,” a military version of the øVagina Monologues.” They dressed up as veterans from World War II, Vietnam, post-Vietnam, and Iraq and Afghanistan. Fry has also started a reference library for veterans in her office. Soon she will get a recliner where clients can meditate. She plans to continue the T-shirt project (also known as the Clothesline Project), which has proved successful across the nation. But she realizes it is not enough. øWomen are still not getting the services that they need. Yes, were in transition, but when do women start getting valued as veterans?” she says. øDo we have to wait until the next war?”û û