Wet Beds

Housing bums could save money, human lives

By Alan Pittman

|

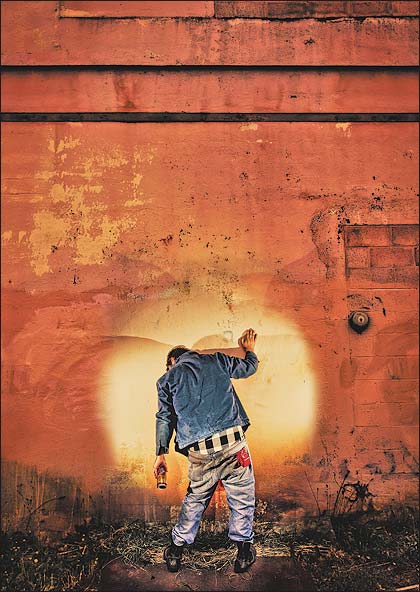

Would Tom Egan be alive today if Eugene had “wet housing” for homeless people who continue to drink or use drugs?

Terry McDonald thinks so. “That would have been a perfect candidate for a wet bed,” said the St. Vincent de Paul director.

Egan, an alcoholic veteran, perished in the snow at 1st and Blair just before Christmas three years ago. With wet housing, “he probably wouldn’t have died,” McDonald said.

“Wet” beds are housing for chronically homeless people who continue to use alcohol or drugs. Over the past decade, hundreds of cities have successfully used such a “housing first” approach for the most troubled street people to save police, jail and hospital costs and save people. Portland has had wet beds for years. Corvallis opened up a dozen wet beds two months ago. But in Eugene, the Mission shelter won’t take people drinking and using drugs, and the city doesn’t have any wet beds.

“We all think that’s something that we would be interested in being able to provide,” Mayor Kitty Piercy said.

But getting the cost-efficient and humane housing innovation in Eugene has been slow. Twenty members of a “blue ribbon” city committee on the homeless recommended the approach three years ago. In January, McDonald pushed for funding as a member of the city Budget Committee, but with no progress.

“Its a wonderful idea and something that is lacking,” said Paul Solomon, director of the Sponsors inmate rehabilitation program. But he said, “nothing has really gone anywhere.”

Save Money

With the tight economy, the most powerful argument for wet housing may be its cost efficiency.

“It would save us a fortune” in police, jail and hospital costs, McDonald said.

Numerous studies have backed up the claim that paying for housing the most needy homeless saves far more money in jail, police and hospital costs. Two years ago the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published a scientific study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The control group study of Seattle homeless people found that a wet bed program cost about $13,000 per year per person to prevent $86,000 per year in police, jail, court, hospital and other costs.

In 2006, The New Yorker magazine reported on the case of “Million Dollar Murray,” a homeless alcoholic in Reno who ran up huge hospital bills before dying on the street.

Eugene’s blue ribbon committee found “very similar” cases of intensely costly homeless people in Eugene.

The PeaceHealth emergency room costs an average of almost $400 a day per person. The Johnson psychiatric unit averages almost $1,000 a day. Detox at the Buckley House costs $220 a day per person. The jail, filled in large part with homeless people, costs $379 a day per bed.

By comparison many cities are able to provide wet beds, including case workers, for less than $40 a day. In Eugene, renting a bedroom costs only about $10 a day.

The wet beds would only have to be provided to a small share of the worst-off homeless people to make a huge impact.

Eugene Police Officer Randy Ellis told a West University Neighborhood Association meeting in January that 80 percent of the problems with street people could be attributed to just 25 people, according to meeting minutes.

Norman Riddle, a White Bird Clinic caseworker, agrees that the worst homeless problem is highly concentrated. Riddle said he remembers troubled individuals from when he started working with the homeless in Eugene 25 years ago. “There are still some of those people out there running around.”

Riddle said a few homeless people show up over and over in the police blotter for jail or hospital transports. “There are people out there that everybody knows,” he said. Even getting a few off the street would save a lot of money, Riddle said. “Twelve would be a big deal.”

In other cities, some have questioned whether focusing money on a relatively small number of the hardest to cure homeless is better than spreading money out to more people that are easier to help.

But McDonald said to save the most money, you have to help the worst to save the most jail, police and hospital money. “They take up the most money per capita,” he said.

Getting the most visible people off the street and into housing could also have a big impact on the city’s multi-million-dollar effort to redevelop a downtown struggling with a perception that the area is plagued by homeless people.

“It benefits us all to get people with a roof over their head and food in their bellies and able to move on with their lives,” Mayor Piercy said.

Save People

“Everybody agrees you have a better chance of helping those people if they are housed,” Piercy said of the chronically homeless.

In addition to the big cost savings, the JAMA study found that wet bed participants drank less.

With caseworkers and medical help provided in wet bed housing, “it allows them to continue to use in a condition that’s safe.” McDonald said. Compared to using on the street, “they live longer and healthier lives.”

Doug Bales, coordinator of the homeless warming center program named after Egan, agrees that housing for alcohol and drug users is needed on more than just the coldest nights.

Even with just a few nights of housing and attention provided through the Egan centers, “these people start to change,” Bales said, citing several people who cleaned themselves up. “It’s really profound,” Bales said. “It just causes a chain reaction with better behavior.”

Ideology

The cost efficiency and humane appeal of the wet bed/housing first approach has had wide appeal, winning backing even from the former Bush administration and congressional Republicans.

But an ideological opposition remains among those who perceive the approach as rewarding the most abusive vagrants with free apartment keys.

“It’s a political thing with people in AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) and NA (Narcotics Anonymous),” said Riddle. “They are hardcore abstinence.”

“There is a need to educate people,” said Piercy of some possible opposition on the City Council.

Wet bed proponents argue that the housing first approach recognizes that drug and alcohol addiction is a difficult-to-cure disease rather than a moral failing. Housing reduces the harm of that disease to society and to the individual. For homeless people statistically unlikely to solve their difficult addiction problems while struggling to survive on the street, wet housing is the only practical, realistic alternative, they argue.

The police pick up drunk homeless people, and “where do they have to go?” Solomon asks. “Really, the only options are the jail and the emergency room, and those are very expensive alternatives,” he said.

But some local conservatives have argued that Eugene’s politics are overly tolerant and attract the homeless. They’ve advocated a punitive approach with police sweeps, criminalization, incarceration and harassment to move the homeless problem out. Some of those opinions were expressed at the West University Neighborhood meeting on homeless problems.

But at the meeting, Police Lt. Doug Mozan said that police have tried to send homeless people out of the community, but they just come back, according to minutes.

The blue ribbon committee report sought to debunk some of the myths that homeless services create homelessness: “Existing assistance programs were actually created as a remedy for complaints from the public related to the impacts of homelessness. The homeless people being served are from this community. Those who become homeless end up in their situation as a last resort, rather than by choice.”

A decade ago the police performed a “sweep” of the homeless in the West University neighborhood targeting street people for jaywalking and other minor crimes. Many were swept to the downtown. Now that the police are in the midst of a sweep of the homeless from downtown using a new exclusion ordinance and added officers, the West University neighborhood is again seeing a rise in problem street people, according to the neighborhood meeting minutes.

McDonald said the downtown police approach has done little but clog the courts. “We’re talking about human beings. You cannot make them sweep and disappear. They’re not dust,” he said.

Cold Cash

But even if wet beds are a fiscal and warm-and-fuzzy “win win,” whether they ever happen in Eugene will come down to cold hard cash.

“We all know that you save money, but you still have to have the money to do it,” Piercy said. “You’ve got to have the original money in place to see that savings.”

The hospital, police and jails may save big on wet beds, but that doesn’t mean they want to share any of their budgets. “Everybody has mentioned it. Everybody wants somebody else to pay for it,” McDonald said.

Already, county and federal cuts are hitting local alcohol and drug treatment programs. “We’re losing some of our housing capacity instead of growing it,” Piercy said.

But hundreds of other cities have creatively solved the wet bed funding problem. In Portland, “the hospitals chipped in,” Solomon said. “It was pretty successful,” he said of the Portland program. “Many of these people were costing the hospitals hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.”

Bales said local hospitals may be able to help with some of the medical supervision costs for wet housing. “That medical liability issue seems to be the big stopping point.”

Corvallis, a city a third the size of Eugene, was able to raise more than $1 million in grants and individual donations and volunteer time to open its wet beds in July.

Other cities have tapped into federal funding, although there are a lot of requirements for sobriety first before housing. Still, wet bed caseworkers could help homeless people get the veteran, disability and other benefits they are entitled to receive to help fund their housing.

Bales said he’s seen an outpouring of generosity to support the Egan Warming Center program. “This community really steps up,” he said. “When it’s time for wet housing, and we get the dots connected, I anticipate the same thing.”

The city could also prioritize a few hundred thousand dollars out of its half-billion dollar budget.

The city is already spending a half million dollars a year on extra police to enforce its “exclusion ordinance” targeting the homeless downtown.

Since FY 2000, the police budget has increased 72 percent to $46 million a year, despite falling crime rates. With only a 7-percent increase in people working in the department, most of that big jump is in added police salaries and benefits.

Police officers got a 3 percent raise last year and pay only 5 percent of their insurance costs. A one- percent trim in police personnel costs would save $377,000 a year, enough for about 25 wet beds. The police department budget now works out to $138,000 per employee.

The police have also added two analysts and one forfeiture coordinator administrative positions in the last year.

A lot of other fat in the city budget could benefit the homeless. The city is spending $16 million in reserves for new offices for the police department. The city spent $2 million in reserves to design a new City Hall that it decided not to build. The city is giving away more than $1 million a year away in tax breaks for high-end, university area apartment developers who critics say would build the same thing without the handout. The city has six PR people costing about $500,000 a year.

But if the city bureaucracy won’t let go of its cash for an essential human service, there’s always the possibility of a tax increase. While the blue ribbon committee was calling for increased funding for street people in 2008, the city successfully campaigned for a $36-million tax increase for street asphalt.

The blue ribbon report recommended a city education campaign and a $5 million property tax levy on the ballot last November, but the City Council did not refer the measure.

A $500,000-a-year levy costing the average homeowner only about $6 a year could fund about 30 wet beds, based on other cities’ costs. Piercy said if people called for such a small tax measure, the council would consider it. But she said after the failure of the school funding measure in May, she’s unsure of its chances at the ballot. “People just don’t know what the capacity is to say yes to things.”

Bum Politics

In other cities the police have played a major leadership and funding role in helping wet beds happen.

But Eugene Police Chief Pete Kerns did not return several calls requesting comment for this story. Melinda McLaughlin, one of the departments’ two PR people, referred questions to local nonprofits. “We are not the right sources for info on wet beds,” she emailed.

But Piercy said Kerns has been supportive of wet beds in discussions with her. “Our police are very interested in this. They think we ought to do it,” Piercy said. “I have heard that numerous times.”

Solomon says the chief did seem “open to it” when he talked to him about wet beds this summer. Solomon said Kerns wanted to bring other people in on the discussion, and hopefully meetings will happen this fall.

Wet beds have happened in other cities when key players in city government, law enforcement and hospitals pushed for it, McDonald said. “I haven’t seen these three sit down and smile and nod and say, ‘Yeah, we’d like to make this happen.’”

Without action, McDonald said federal and county cuts, unemployment and dysfunctional health care are combining into a “perfect storm” for the homeless problem this year. “It’s hard to watch.”

But Riddle said he thinks Eugene can come together to get the wet beds idea done. “Fly it out there and see what happens,” he said. “There are a lot of people out there who would like to find some solution, because they are tired of seeing people out in the bushes on their way to work.”

Other cities have been doing wet beds successfully for 15 or 20 years, Riddle said. In Eugene, “I think it’s an idea whose time has come.”