If I Only Had a Brain

Whats wrong with The Boys Next Door?

by Rick Levin

Everybody loves a “retard.” There is something about the unsullied innocence of the mentally challenged that acts on our sentiments like a tonic ã as though we who have bitten the rotten apple of knowledge, we who are perfectly normal and completely sane, are offered a moral compass by the pure, childlike actions of those simple, silly people too pure to understand all of our tangled hypocrisies and devious schemes.

|

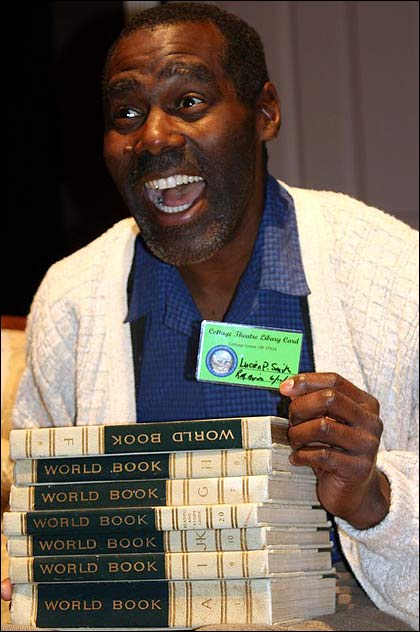

| Lemuel D. Wilson in The Boys Next Door. Courtesy of Cottage Theatre. |

From Rain Man to Forrest Gump to Slingblade, movies are fond of regularly recycling one of American societys founding beliefs: That the mentally disabled, motivated by nothing but unfiltered truths and unchained hearts, can show us the way to salvation. They show us how to be good. They show us how to love. They show us how to order French fries and serve our country with honor. The “retard” is our safe and secular Christ.

All of the above is, of course, complete bullshit. The Myth of the Good Retard is the opiate of the masses, a seductive consumerist fantasy as full of smoke and mirrors as anything Orwell ever dreamed up. But wait, you say, whats so bad about a mentally disabled individual showing us the error of our ways? Good question. Aside from the fact that this myth has but one foot in reality, there is this: The notion that the mentally challenged (like children) are beacons of morality in a corrupt world is an escapist diversion, an inverted formula that absolves us of responsibility by working on our hearts rather than our heads ã it chokes off all questioning in the very act of inspiring it.

Life is not like a box of chocolates, unless you are a type-one diabetic with a terminal sweet tooth.

The Boys Next Door, written in the early •80s by Tom Griffin and currently in production at Cottage Theatre, is a highly sentimental, sometimes maudlin, flatly comic and essentially false depiction of four mentally disabled men living together in a small apartment near Boston, all of them presided over by a burnt-out but goodhearted caretaker named Jack (George A. Comstock). The play has next to no plot; action is advanced by the daily routine of slapstick and sorrow that makes up the lives of “the boys”: talkative, nervous Arnold (Scott MacWilliams), schizophrenic Barry (Dale Light), illiterate but literal-minded Lucien (Lemuel D. Wilson) and rotund, emotionally explosive Norman (Achilles Massahos). Its like an after-school episode of Seinfeld written by Ronald Reagan.

Director Reva Kaufman and her cast and crew do what they can with a script that is flawed and wrongheaded to its core. No doubt Griffin wrote Boys with the best of intentions, hoping to dismantle long-held prejudices about the mentally disabled, but you know what they say about good intentions. Griffins road to artistic hell rests somewhere in his inability to mold his milquetoast do-gooderism with anything resembling artistic integrity. The play has no symmetry, no inner coherence, no guts, no grit and therefore no point. It comes across as a work of theater written by an 8th grader, overloaded with obvious jokes, easy emotions and porkpie platitudes about the mentally challenged that, in the end, reinforce rather than deconstruct accepted stereotypes.

During a social dance for mentally disabled adults, caretaker Jack wonders aloud whether the gathering is the saddest place hes ever been, or the happiest. Its a disturbing, intriguing moment of queasy ambivalence that is left utterly uninvestigated. A handful of such hopeful moments, similarly discarded, only serve to highlight the poverty of the play, which doesnt even have the convictions for the courage it lacks.

For instance, when schizoid Barrys one-armed father, Mr. Kempler (Dave Kessler) ã a thoughtless, gruff blowhard with no idea how to approach his sons illness ã comes to visit, he says to Barry about Lucien, “I heard your roommate was a darkie,” soon after which Mr. Kempler predictably hauls off and smacks his mute son. Um, darkie? A one-armed bigot seething with rage and confusion in Massachusetts circa 1980 does not say “darkie”; he says “nigger.” If you feel that word is inappropriate and offensive in this particular context, then you arent ready to hear the truth ã about mental disabilities or race or anything else. But youll appreciate The Boys Next Door.

Or maybe youll love it: Love it just as much as the gum-smacking, seat-kicking, burping and continually loud-talking middle-aged women sitting behind me during the production loved it. They laughed riotously at simply everything, as though they were watching an episode of The Three Stooges. Near the end of the first act, one of these ladies, who did everything but fart during the play, suddenly broadcast aloud her undisturbed feelings about the awkward, fumbling dance of two mentally challenged adults. “Theyre the cutest!” she squealed.

Cute. Cute like babies. Cute like old people and puppies. Cute like a crock of chocolate in the lap of Forrest Gump.