As an educator and as an architect, making the case against recommendations to improve Eugene’s schools may seem difficult. Our children deserve the very best facilities and access to the highest quality education. However, the recommendations in a recent 4J Facilities Master Plan study are so flawed that the case against them is quite easy to make.

In terms of building type, the recommendations ignore overwhelming research on the academic value of small schools and disregard the evidence supporting neighborhood schools. In terms of process, the evaluation metrics are skewed to justify new construction, the effort failed to account for citizen input, and the naïve hope for funding misinterprets Eugene politics.

|

|

|

The district is certainly in a bind. Administrators are running out of money to operate their 35 school buildings, yet many of these same buildings have so much deferred maintenance that the district now may be asking voters for money to either demolish or abandon and replace about 25 percent of its building stock. The recommendations call for the cash-strapped district to replace North Eugene High School and Roosevelt Middle School, as well as Willard and River Road elementary schools. It also calls for combining Howard and Corridor elementary schools into one large new building and doing the same for Edison and Camas Ridge.

The focus on new construction, however, seems odd given the recent round of layoffs, furlough days and program cuts the district has implemented. Granted, these are two separate pots of money (capital costs vs. operating costs), but to most taxpayers the distinction is largely irrelevant. The ambitious plan has little community support, which is unsurprising given the lack of community input in the plan’s creation.

While the goal of ensuring that equitable resources exist for all Eugene students is laudable, the approach to achieving that goal needs to be based on broad community input. What is clearly missing is a facilities planning vision that can support the district’s mission. As it stands, the “vision” the study seems to promulgate is for cost savings through consolidations, new buildings in place of old ones, and consolidated schools over neighborhood schools. But all three of these goals are based on myths, not reality.

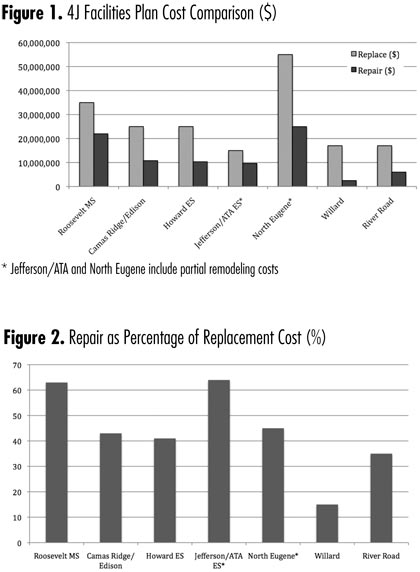

Myth: Consolidation saves money

Reality: This proposed construction and consolidation program will cost Eugene taxpayers an estimated $186 million, not including financing costs on the three proposed bonds. This is $100 million more than upgrading existing schools. If these buildings were repaired, the study determined the cost would be $86 million (see figure 1). The consultant who prepared the study justifies this significant additional cost because the new schools are forecasted to cost up to $700,000 a year less to operate. This fails, however, to account for the more than $6 million annual bond repayment cost and the reduced operating costs of renovated schools. Spending $6 million a year to save $700,000 a year does not pass the commonsense test.

It is also a forecast that is most likely wrong. According to researchers at the University of Massachusetts, numerous studies over the last 50 years have “shown that over time consolidation has not resulted in any significant savings, and reductions in per-pupil costs have been very little if at all.” These researchers did find that for the first year following consolidation administrative costs are lower, but this lasts for only one year “as larger organizations have a strong tendency toward creating more extensive and costly administrative bureaucracy within a few years.”

The University of Massachusetts findings support a 1992 study by the Public Education Association of New York that examined existing research on school size and operational costs and concluded, “The premise that small schools are more expensive to operate has always been false.” Educational researcher Stuart Grauer explains why this is the case: “Large schools actually exhibit diseconomies of scale: inefficiencies and increased costs that result from increases in administrative bureaucracy, security costs and transportation costs.”

Myth: Old school buildings cannot be effectively repaired

Reality: According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, school districts across the country from Spokane to Boise to Miami have remodeled old and historic schools with the very latest in computer technology, life-safety techniques and handicap accessibility. Sadly, demolition by neglect is a common tactic used by less enlightened districts. Such a tactic should not be rewarded in this era of sustainability. At the same time administrators are asking students to recycle newspapers, they should not be sending entire buildings to the landfill.

In reading the 4J study, it is abundantly clear that the problems are not building failures. The problems are maintenance failures that should be addressed by a more robust maintenance program rather than by demolition or abandonment. But the consultant preparing the study is well known for making recommendations in support of costly new construction. Three schools are good illustrative cases that expose the flaws in the study’s methodology.

Roosevelt Middle School

Built in 1950, Roosevelt does indeed have some flaws. The report found that the foundation at the band room is spalling (flaking), E wing is settling and has cracked walls, B wing’s concrete floor has settled some, areas of brick need cleaning, wood soffits have moisture damage, the roof has blisters and leaks, the tile floors in some classrooms are cracked and stained, many interior walls need repair and painting, ceiling tiles are stained, most of the fixed equipment (lockers, bleachers, cabinets, etc.) is old and worn out, many plumbing fixtures, boilers, heat pumps, unit vents and radiators are at the end of their service life, there is no air conditioning (a fatal flaw perhaps in Texas but not in Eugene), some light fixtures are old, some exits lack handrails, and not all restrooms are accessible by wheelchairs. To fix all of these problems, the consultant estimated a $21.9 million cost. A replacement school would cost $32 million.

Camas Ridge Elementary

Built in 1949, Camas Ridge is admittedly no architectural gem, but that has not stopped teachers and parents from creating a very positive learning community. The depth of the consultant’s analysis is almost laughable when used to justify demolition. The 417-student school’s roof may have a leak over the gym, the single pane windows need to be replaced, some carpeting and paint are worn, the main electrical service, water lines and floor tiles are at the end of their service life, the boilers are old and energy inefficient, there is no air conditioning, many light fixtures are old with yellow lenses, and “a lot of walls with wood paneling” are a problem. To fix the problems with Camas Ridge, the district would need to spend roughly $5 million. Replacement would cost about $12.3 million.

Edison Elementary

Like Camas Ridge, teachers and parents at Edison have created an excellent learning environment for the school’s 346 students despite the building’s supposed flaws. Built in 1926, Edison’s deferred maintenance has led to the following problems identified by the consultant: older windows are single pane, some doors need paint and have old hardware, some toilet partitions are at end of their service life, classroom cabinets are showing some wear, some drain lines are slow, the boiler is at the end of its service life, the stair lift is slow, many classroom doors have large areas of glass, and many areas are not directly accessible by wheelchair. The consultants also claim that the main building has unspecified seismic concerns, which is not surprising for an older building. Engineers and architects have the technology to make appropriate and fiscally responsible seismic upgrades. Edison has a replacement cost of about $12.6 million and a repair cost of approximately $5.7 million.

I could go on describing the various problems at the other schools the report recommends replacing, but there is no need. The problems are all about the same. They are generally issues of maintenance that should not be used to justify replacement. If the community passes yet another bond, it will act as an enabler and the district will be back again asking for more money to replace even more schools it has failed to maintain.

To determine which buildings should be abandoned or demolished, the consultant established an arbitrary baseline using an arbitrary weighting of four criteria: building condition, educational suitability, site condition and technological readiness. If a building scored below 70 (whatever that really means) then that building should be replaced. But if that baseline were changed to 60, then only one building would need to be replaced and that would be Roosevelt. Who determined 70?

A more realistic metric is to determine if it is a good investment to fix a building rather than replace it. On most buildings owned by the U.S. government, for example, replacement is justified only if the repair costs exceed 70 percent of the replacement value. An even stricter measure has been used by the state of Washington, which has used 80 percent as the cutline for its schools. Using these metrics, 4J could not justify any replacement since the repair costs for any of the buildings does not exceed 70 percent of the replacement cost (see figure 2).

Myth: New and bigger buildings improve performance

Reality: The two new consolidated elementary schools proposed in the study are much bigger than the ones they may replace. These schools would each enroll about 600 students — more students than any elementary school in Eugene. However, research into small elementary schools, which are generally defined by the Education Commission of the States as enrolling no more than 300-400 students, clearly demonstrates the value of smaller schools over their newer and larger counterparts.

Many districts are now returning to the small school model given the enormity of evidence in support of such schools. In early 2012, for instance, New York City School Chancellor Dennis Walcott reported on a study of 105 small schools and concluded that these schools “changed thousands of lives in New York City, across every race, gender and ethnicity — not only helping them graduate, but graduate ready for college. When we see a strategy with this kind of success, we owe it to our families to continue pursuing it aggressively.”

Academic Performance

While socioeconomic factors play a primary role in academic performance, a study of 293 public schools by the National Center for Education Statistics found that school size was the second best predictor of student performance and graduation rates. Educational researcher Kathleen Cotton analyzed 103 studies of school size and found that the data overwhelmingly supported small schools because they have higher attendance rates, higher student achievement and less violence. She found that “small schools are superior to larger schools on most measures and equal to them on the rest. This holds true for both elementary and secondary students of all ability levels and in all kinds of settings.”

Researchers in New Mexico found that small schools improve graduation rates and student achievement because they counteract alienation, isolation and disconnection in part because such schools have less violence, crime and classroom disruptions. They also found that small schools enable low-income students to succeed at the same levels as students from more privileged backgrounds, which helps to narrow the achievement gap.

Teaching Performance

An extensive study of school size by educational expert Stuart Grauer found that small schools offer better teaching conditions. In small schools, teachers use a broader range of teaching styles, have greater connection with parents, have more opportunities to collaborate, and they have “higher job satisfaction and sense of responsibility for ongoing student learning.” Creating positive environments for 4J teachers should be a top priority.

Student Participation

Educational researcher Susan Black found that small schools create more opportunities for participation per capita — more students participate in more kinds of activities. And another study found that because small schools need a large percentage of students to fill each activity, they “engage a broader cross-section of students, helping reduce social and racial isolation.” In addition, researchers from Ohio University and Marshall University found that students who participate in activities and feel connected at school have higher achievement, are less likely to drop out, have higher self-esteem, attend school more regularly and have fewer behavior problems.

Parental Involvement

Numerous studies have found that small school parents are closer and have higher levels of parental involvement, which is a critical factor in student success. William Bogart of Case Western Reserve University concludes that one effect of consolidation may be that, by making it harder for parents to get involved, it harms the quality of schools: “It makes it more difficult for students to participate in after-school activities relative to the case where they can walk to and from the school.” Bogart also found that closures of neighborhood schools results in a property value decrease of 9.9 percent. This is a significant finding: The 4J proposals may reduce property values and much-needed property tax revenues.

Curricular Choices

Advocates of large schools falsely claim that such schools give students more curricular choices. In an extensive study, University of Missouri scholar John Slate found, “Increasing school size, especially beyond 400 students, does not typically result in a large increase in curricular choices.”

Environmental Performance

One final problem with large schools is that they cannot effectively operate as neighborhood schools to which most students can walk and in which the school becomes a center of community life. Bigger schools draw students from a much wider geographical area, which generally means more students are driven or bused to school. If the 4J plan proceeds and consolidates Edison at Camas Ridge, for example, roughly half of Edison children will not be able to walk or bike to school anymore. The distance will simply be too far. In this era of skyrocketing childhood obesity and climate change concerns, schools should be looking for ways to increase walking and biking rather than becoming part of the problem. Less walking and biking will mean more driving, increased carbon emissions, more asthma-inducing air pollutants and heavier children.

A Different Path

In 2011, Eugene voters approved Measure 20-183 to fund $70 million in repairs to schools across the district. The funds will fix the very problems that have been identified in the 2012 report, including major system repairs and replacements, additions and remodels and technology upgrades. Unfortunately, schools now slated for demolition or abandonment were part of the sales pitch for last year’s bond. For example, Edison was to be allocated $900,000 to upgrade its kitchen and staff offices. This is one reason why I voted for that bond measure.

So last year the district thought these types of problems could be addressed with sensible repairs. But this year, the district thinks these problems justify demolition and abandonment of eight buildings. The recommendations were clearly driven by the consultant’s flawed mathematical model and the new superintendent’s desire to make a quick change rather than by a well-conceived, community-based process.

In advocating for the 2011 bond, former Eugene School Board member Eric Forrest wrote, “Reflecting the times we’re in, this isn’t a sweeping grand plan to add spanking new buildings … Rather, it’s a responsible, prudent measure that does what every single one of us knows makes the most business sense — taking care of what we have so that future, more costly repair or replacement costs are deferred or avoided altogether.” That is the kind of thinking 4J needs now. Given the mountain of evidence in support of small schools, the substantial cost premium for new buildings and the relatively minor upgrades that 4J schools actually need, the case for repair over replacement and consolidation is easy to make.