There was a time when the thump thump thump of electronic dance music was confined to abandoned warehouses and private basements or tucked away deep in the Willamette Valley’s forests and mountains. Jordan Cogburn likens finding a rave in the ’90s to a scavenger hunt. Step one: Find the party’s flyer (through a friend or at a record store). Step two: Call the number.

“You’d call the number on the flyer and they’d tell you to go to this spot. You’d go over to this spot and there would be a dude waiting in a car,” says Cogburn, drummer for local bands Dirty Spoon and Breakers Yard. “He’d hand you a map and he’s like, ‘OK, you gotta go to this other spot.’ Then you’d go to this other spot. Then they’d tell you where the party was actually at. Then you’d go out to that party.” He continues, “You get there and it’s out in the sticks, out in the middle of nowhere. You’re driving up this dirt road; you can’t see anything except for what’s in your headlights. Then you get out there, you’re partying, partying, having a good time. All of a sudden the sun starts coming up and you realize you’re on a 150-foot cliff!”

Times have changed.

“So now that you can just ride your bike down to the Cuthbert, it’s like ‘That’s boring. You took all the fun out of it! It’s no longer a hunt.’”

Boring or not, it’s indisputable that the underground electronic dance music (EDM) scene in Eugene has bopped its head above ground. Warehouses and basements have been swapped for more mainstream venues like WOW Hall, McDonald Theatre and the Cuthbert Amphitheater. In the past year alone, Eugene has been flooded with EDM acts, from local bands Hamilton Beach and Medium Troy, to the national — Odesza, Beats Antique, Candyland, Pretty Lights — and the international — Dillon Francis, Disclosure and Daedelus. McDonald already has two big EDM acts on the docket for fall: Zedd and Zeds Dead. And those secret gatherings in the woods? They have morphed into throbbing, day-glo festivals with sponsors like the recent Human Nature Festival in Tidewater, Ore., the Paradiso Festival at Washington’s Gorge Amphitheatre and the upcoming Kaleidoscope Music Festival at Mount Pisgah’s Emerald Meadows featuring some of the biggest names in EDM like Bassnectar, DJ Shadow and Lotus. And where the music goes, the culture — dance, fashion, ecstasy (the preferred EDM party drug) — will follow. Whether the scene likes it or not, EDM is the new mainstream on the national stage. Eugene is no exception, but it has an EDM history, culture and, perhaps, a future all its own.

|

| Jordan Cogburn sifts through fliers from his dj days as dcndr |

WHEN I WAS YOUR AGE

“In general terms, EDM has burst onto the scene in such a quick way, changing what is considered pop music with layered electronic beats, in almost every genre today,” says Mike Hergenreter, talent buyer for Kesey Enterprises. “The scene has infiltrated the youth, with the media picking up on it just as quickly, and selling the sound almost everywhere you go — radio, commercials, movies — EDM is pop music today.”

EDM, with its dance-ready beats and heavy drops, is indeed the pop music of today, but its popularity is a relatively recent phenomenon. Known in the past as electronica, techno, club and rave music, EDM is a broad umbrella that covers ever-splintering electronic genres: trance, house, glitch-hop, moombahton and too many others to list here. Many believe its roots go back to the disco era. Longtime event producer Phillip Blaine for Insomniac Events (Electric Daisy Carnival) traces the movement’s origins back to the ’70s with bands like Kraftwerk. The ’80s saw electronic outfits like New Order and Frankie Knuckles leading to a slew of ’90s artists such as Paul Oakenfold, Moby, Prodigy and Daft Punk paving the way for today’s popular EDM artists Skrillex, deadmau5, Bassnectar, Swedish House Mafia and many more. This spring’s ubiquitous “Harlem Shake” is trap, another subgenre of EDM.

But, according to WOW Hall publicist Bob Fennessy, “This isn’t the first time that the electronic trend has come around.” In the ’90s and early aughts, the venue hosted “Magical Thursday” events once a month. “It was very popular,” Fennessy says.

Cogburn, who deejayed in the area for 10 years under the name DCNDR, originally joined the scene at 17 because of a Magical Thursday flyer that he came across in his hometown of Cottage Grove. He remembers sneaking out with some buddies and driving to WOW Hall one Thursday night in 1999.

“People are smiling, people are having a good time, it’s a dark room — sweet,” he remembers thinking. “I was like, ‘This is for me.’” Cogburn started helping set up and tear down EDM shows so he could get in for free to see the big acts they were pulling in, like the U.K.’s DJ Dara. In the process he met many players in Eugene’s original EDM scene — music promoters Real Kidz, the Stylus Grooves record shop people, DJ Mattie Mataus, the rave crews Joy Scouts, Vujadé and Gaia Tribe. Like many scenesters, he went through the “candy raver” (think neon and plastic beads) and “fat pants” (“Bell bottoms? No, they’re not big enough. I need something I can sail away on,” he remembers) phase, but before long, Cogburn ditched the neon look and became a self-proclaimed “drum-and-bass jungle head” (a genre of EDM with heavy bass and sub-bass lines and fast breakbeats), deejaying at underground word-of-mouth parties. There were the “breaking-and-entering” warehouse parties, the BMX track parties and the astrological “sign” parties hosted in the basement of a former salon on Oak Street — parties that dissolved in minutes as soon as there was any word of the fuzz.

“You’d have your main house trance room where it was like a big dance party kind of thing. Sometimes you’d have a down-tempo room,” where people could relax and cool off from ecstasy (a common side effect is hot flashes) and dancing, he says. “Then there would be the edgy room with all the junglists.” Cogburn remembers the morning of one sign party when Mataus was deejaying. “We’re going hard. The generator cuts out or the breaker pops or something. So there are no speakers. Turntables with a needle and a record? You can hear the sound coming off the needle. Everyone rushes the DJ booth,” he says, mimicking putting his head down to a turntable and moving to a silent beat. “We’re just going to keep dancing. … Since the beginning of time, that’s all people want to do is shake their ass.”

Magical Thursdays came to a close in the early aughts. Fennessy says that it was around this time that hip hop began dominating Eugene’s music scene, and EDM went back underground. For Cogburn and many others, it was the introduction of Scratch Live (also known as Serato) — vinyl emulation software that uses digital audio files — into the music producer’s toolbox that marked the end of his deejaying days. “I faded out of the scene mostly due to Serato. I couldn’t beat it anymore,” he says. “I couldn’t afford to pay the 500 bucks to buy a piece of DJ equipment while I [was] going through school.”

|

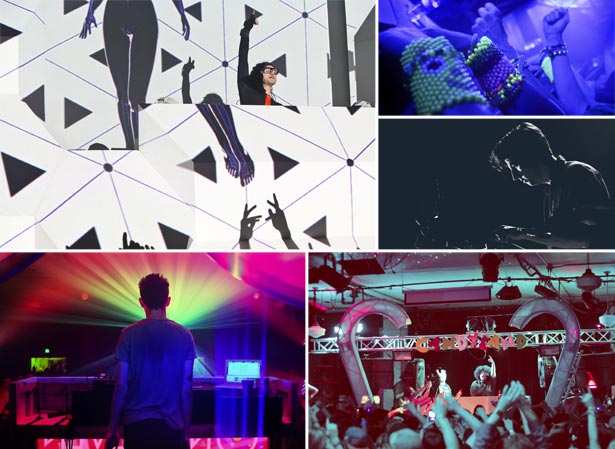

| Clockwise: Skrillex at McDonald Theatre, PLUR people ‘kandi’ bracelets, Jamie XX at McDonald Theatre, Candyland at WOW Hall, Mord Fustang at WOW Hall. Photos: Candyland, bracelets and Ford Mustang by Athena Delene, Skrillex and Jamie XX by todd cooper |

KIDS THESE DAYS

Athena Ortmann, 19, describes entering Oregon’s millenial EDM scene as a culture shock. Raised in a conservative Mormon home in Springfield, one of her first concert outings was seeing Israeli dub-step producer Borgore at the Roseland Theater in Portland when she was 17; for her, it was a “completely new world” of music, lights and people. “An EDM show is one thing and a concert is another thing,” she says, laughing. “It’s not like going to Mat Kearney.” Her first EDM show in Eugene was Beats Antique — it wasn’t long before Ortmann was hooked and photographing shows like Candyland and Disclosure at WOW Hall.

Now a freelance photographer and a media director for OneEleven (the production company behind Kaleidoscope Music Festival), and hot off attending the Paradiso Festival, Ortmann knows the Pacific Northwest EDM culture well, describing it as “tribal.” In today’s lingo, the term candy raver has been replaced by kandi kids and PLUR people — PLUR is an acronymn for “Peace, Love, Unity, Respect,” a kind of EDM mantra with roots that date back to the mid-’90s U.K. club scene. Snarky, candy-colored tanks with phrases like “Maybe Partying Will Help,” fishnets, furry boots, glitter — these items make up the kandi kid wardrobe. There’s even a special PLUR handshake. Ortmann says the handshake goes like this: Two people make mirroring peace signs (peace), then curve their hand into half a heart each (love), followed by connecting their palms and interlacing their fingers (unity). Then each will slide one of their plastic bracelets — usually spelling out their rave names or a favorite artist — off their own wrist and put it on the other (respect).

However, PLUR people only fall on one part of the EDM spectrum. “Within the past few years EDM has just become so mainstream,” she says. “It’s so funny to me to see sorority girls and frat guys at this stuff because it’s like, ‘Oh, are you dirty rave kids now?’ It’s like the new toga parties.” Ortmann and Cogburn both note the rise of dubstep on the national scene — like the aforementioned “Harlem Shake” and Skrillex — for the shift in public opinion (although Cogburn prefers the term “bro-step”). Dubstep stems from “drum-and-bass-jungle” and reggae music.

Ortmann shrugs and explains that Eugene is a college town so it’s natural that students are attracted to music with a built-in dance party aspect. But party tunnel vision can also usher in a crowd that is in it for the drugs, namely Molly (said to be the purest form of ecstasy). Preferred by partygoers for its euphoric high — a world of fuzzy affection, high energy and a heightened sense of touch — Molly (aka MDMA) can also cause dizzying anxiety and depression, hot flashes and chills and lead to severe dehydration. Washington’s Paradiso Festival saw dozens of drug overdoses — attributed mostly to Molly — and the death of a 21-year-old Washington State University student. Cogburn remembers ravers taking one or two hits of ecstasy in the ’90s but explains that now people are taking upward of six or seven hits. “Why are you trying to get so high?” he asks rhetorically. He also points out that there used to be “party smart” booths, educating partygoers about recreational drug use.

“Eugene and Springfield should take heed of what just happened at the Gorge with this festival that USC put on and understand, hey, people are going to get real loose,” he says of the upcoming Kaleidoscope Music Festival.

Nathan Asman, frontman for local live electronic act Hamilton Beach, has noted this shift as well. “It’s starting to be that going to an electronic show, the people don’t go to see the music, they go to get as fucked up as humanly possible,” he says. “I think that it’s devaluing the music a lot, but on the other hand there are responsible drug users and that’s fine; it enhances the experience.” Ortmann points out that, even if the EDM music stopped, “those people would be doing it anyway.”

“The bottom line is responsibility of the parents,” Fennessy says. “Do you know where your child is tonight? But that’s how it’s always been.”

Hergenreter, booker for the McDonald, notes, “Since our first EDM show, which used to be all ages, we have added age limits allowing the more mature fans to enjoy these shows.”

KALEIDOSCOPE KIDS

One reason for the sea change in Eugene’s EDM scene is OneEleven Productions, a local production company. Phoenix Vaughn, a former DJ, started OneEleven in 2011 after seeing the community’s positive response to electronic beats. Jason Lear, who works alongside Vaughn at OneEleven, says, “This last season we had eight weeks in a row of shows.” Those shows included big names in EDM like Mord Fustang, Adventure Club and Dillon Francis at the WOW Hall, Dada Life and Excision at McDonald Theatre, as well as Zomboy and Bro Safari at the venue formerly known as The Rok. And the shows keep coming this fall, with dubstep producer Rusko already booked at the Lane Events Center in November.

Vaughn hints at a new venue downtown that will serve a more scaled-down crowd of 500 or 600 that could potentially offer OneEleven a platform to book acts that wouldn’t necessarily sell out the McDonald or Cuthbert.

But for now Vaughn and OneEleven are pouring their energy into the Kaleidoscope Music Festival, set for Aug. 23-25, which they have deemed a “fusion” fest, with music ranging from hip hop to folk to dubstep.

“We started as an electronic company because we know the music and we love it, but we love a lot of kinds of music,” Lear says. “We’re eager to share not just the side of OneEleven that people have seen but our love for all kinds of music and our respect for the preferences of everyone in the community.”

The emphasis, however, will be on EDM; of the sprawling 87-act roster spread out over three days, 53 of the artists will be rooted in electronic production and performance. So, as the kids say these days (or at least the neon tank tops they wear say it for them), “Keep Calm and Rave On.” But don’t forget the older credos: “Peace, Love, Unity, Respect” and “party smart.” Oh, and drink lots of water.

EMERALD MEADOWS CONTROVERSY

Outdoor music festivals bring joy for participants, but they can bring headaches for nearby neighbors. Local watchdog group LandWatch Lane County filed a “notice of intent to appeal” to the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA) on July 1 about the recent upsurge in outdoor spectacles at Emerald Meadows in Lane County’s Howard Buford Recreation Area. Emmons says the group is looking into the feasibility of also filing an injunction — which would means the events in question would not be allowed until LUBA made a decision.

In a recent EW viewpoint, LandWatch president Bob Emmons wrote “the mass gatherings occurring for years at a Buford site called Emerald Meadows have been piggybacked onto a 2003 county permit for a small campground and caretaker’s residence.” Nearby landowners off Seavey Loop Road, including former congressman Jim Weaver and farmers Jim and Mary Evonuk of J&M Farms, say the traffic and noise affect their ability to sleep and in the case of the Evonuks to work on their farm.

Emmons writes that allowing the festivals “was done without regard to a state statute limiting the annual amount and frequency of events attracting over 3,000 people and requiring a public hearing.”

UO architectural historian Richard Sundt, after hearing of the LUBA case, wrote a letter to the Lane County Parks department pointing out that events at the park are visible to hikers on Mt. Pisgah’s north slope. Sundt also went out to Pisgah during the Cascadia Music Festival and hiked that slope, which has views of the nearby The Nature Conservancy lands under restoration. He reported hearing music from the festival on that hike and in other areas of the park. “So we now have in this natural area both noise and visual pollution, music and cars,” he writes in a document he sent to LandWatch.

A spirited discussion of the LandWatch intent to appeal between supporters of the festivals at Buford and those who have concerns about the noise, environmental effects, sanitation and traffic is taking place on EW’s website. Crista Munro of Sea Level Productions, which put on the Cascadia fest July 5, writes, “At no time did we experience any traffic issues, either with people entering or leaving the park. We offered each of our Seavey Loop neighbors complimentary tickets to the event, and many of them took us up on it. We provided them with a contact number for our site manager in case they experienced any issues as a result of our event and we did not receive a single complaint before, during or after the event.”

— Camilla Mortensen