The burden of the history is something to keep in mind when face to face with Kara Walker’s elegant, complex and challenging silhouettes depicting the horrors of the antebellum South — images that have been described as an “apocalyptic carnival” — that will be on display for the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art’s upcoming exhibit Emancipating the Past: Kara Walker’s Tales of Slavery and Power opening 6 pm Friday, Jan. 24. Emancipating the Past is the first-ever solo exhibit by an African-American artist at the JSMA.

The New York-based artist’s blockbuster show, 60 works from the collection of JSMA’s namesake Jordan Schnitzer, is important to Eugene for several reasons: On the surface, it’s a reminder that contemporary art is alive, well and relevant. And that good contemporary art can change minds and expose populations to differing perspectives in ways that no other medium can. A show like Emancipating the Past is also an opportunity for a place like the Willamette Valley to reflect on its own racial history and politics through a national lens; how local history — like that of Eugene’s 1951 cross burning targeting an interracial couple — and more recent history — the 2008 bouts of blackface masked as “school spirit” at Oregon State University — as well as the ongoing local celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, fit into the national narrative and legacy of slavery, power and racism.

History is a burden we all share. It’s not Black History. It’s not Women’s History. Or Gay History, or the History of the South. It’s everyone’s history.Welcome to the world of Kara Walker. Our world.

Racial Profiling as Art

“Kara Walker is, I think, the preeminent African-American artist working today,” Jordan Schnitzer tells me over the phone from Portland. Schnitzer has amassed one of the largest collections of contemporary art prints in the country — about 8,000 total, including Walker’s. The son of Arlene, one of Portland’s top advocates of the arts who founded the Fountain Gallery, and Harold, a businessman and philanthropist, Schnitzer developed a commitment to investing in art at a young age. All the exhibit pieces — silkscreen prints, cut-steel sculpture, videos, wall painting — come from his own collection. “When I first saw her work, I didn’t know who she was, I was grabbed … by the power, the passion and the pain of both the themes that were presented and the depth of the artist bearing her soul.”

In 1997, at the age of 27, Kara Walker became the second-youngest person to receive the MacArthur “genius” grant. Ten years later, she was named one of Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World.” But it was back in 1994, fresh out of graduate school, that Walker first took the art world by storm with a piece entitled “Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” — a tongue-in-cheek subversion of Gone with the Wind. With the enormous mural composed of black paper silhouettes — what would become her signature technique — Walker introduced audiences to the themes that continue to run through her work: race, power, revenge, sexuality, gender, violence and identity. Walker, busy preparing for a European exhibit, was not available for an interview.

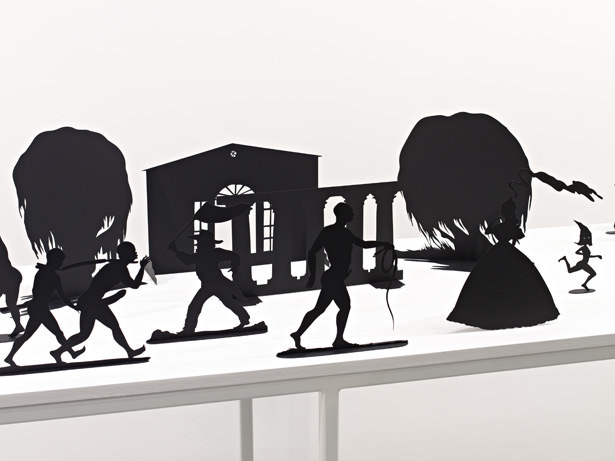

The same year that Walker received the “genius” grant, Schnitzer began his Walker collection with a limited edition print of “The Keys to the Coop,” another silhouette study featuring a young woman on the verge of devouring a decapitated chicken head, which will be on display at JSMA. Other works on view include the prints “I’ll Be a Monkey’s Uncle,” “African/American,” “Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated): An Army Train,” the painted steel-cut sculpture “Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching” and a puppet-shadow video.

But the show’s magnum opus is “The Emancipation Approximation,” 26 framed screenprints that will be hung in succession in the JSMA’s Barker gallery. Jessi DiTillio, curator for the show, let me see a mocked-up model of the exhibit in the basement of the museum; even at dollhouse scale, the “Emancipation” series is unnerving and perversely beautiful. Walker’s response to the Emancipation Proclamation — the 1863 executive order that freed slaves in the union’s rebelling states (although many would argue the accuracy of that claim) — the piece features black and white silhouettes against a slate blue backdrop: swans and slave owners copulating with women, cackling and dancing gentry men, a woman giving birth while a child stands ready to squash the baby, decapitated heads. DiTillio, whose UO master’s thesis centered on the artist, writes of the piece: “Walker has alluded to the Greek myth of Leda and the swan, in which Zeus assumed the form of a swan to rape and impregnate the mortal woman. Drawing on the whiteness of the swan, the allusion mythologizes the tragic history of rape perpetuated on female slaves by their masters, a trope that appears frequently in Walker’s narratives.”

In “The Emancipation Approximation,” viewers will meet several of Walker’s reccurring characters: hyper-exaggerated silhouettes of racist and sexist stereotypes of blacks, which she has described as “pickanninnies,” “mammies” and “Uncle Toms,” and the plantation-owning white aristocracy portrayed as sadistic, irreverent, perverse, ignorant and casually violent. University of Pennsylvania art professor Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw writes of this stereotyping, “often African-Americans found their facial features, the key content of portraiture, to be perceived by whites as interchangeable and undistinguished, and that by invoking such racist assumptions white artists actively created and perpetuated a visual tradition of negative or thoughtlessly stereotyped representation of blacks.”

Walker’s art is a caricature of a caricature; she turns the volume up on the white patriarchy’s offensive portrayal of African-Americans and swings it back around to its perpetrators, exposing the absurdity of it all. She does not mince words or images; viewing her work is a painful and transcendent experience. Walker has said of her oeuvre: “One theme in my artwork is the idea that a black subject in the present tense is a container for specific pathologies from the past and is continually growing and feeding off those maladies,” or what she calls “black muck.”

The Medium is the Message

With Walker’s work, the ubiquitous silhouette is not simply an aesthetic choice; it’s a historically significant one. “She uses a very analog process,” DiTillio says, like 19th-century printmaking, 8-millimeter film and silhouettes. Silhouettes originated in France with the Marquis Etienne de Silhouette, an 18th-century French finance officer of the court and a notorious penny pincher.

“‘Silhouette’ became a derisive slang term for anything cheap. During this period, black cut-paper silhouettes became immensely popular all over France as an inexpensive alternative to painted miniature portraits,” DiTillio writes. This method was also adopted by the slave trade in the U.S., which created silhouettes of slaves as a means of documentation. Walker has doggedly studied the art form’s history, as well as the black memorabilia and minstrel shows of Antebellum America, commenting that her art is “two parts research and one part paranoid hysteria.”

The use of silhouettes, which rears its head in her sculpture and video work as well, also puts some of the accountability on the viewer. Looking at the flat silhouettes, viewers tend to automatically categorize the characters as African-American or Caucasian. “How do I know this character is black or white?” asks DiTillio, ruminating about the imprint that stereotypical imagery has left on society’s consciousness. “Think critically about these images and how they are projecting themselves on art.”

Standing in the shadow of these charged works, it’s not uncommon for the viewer to want to simultaneously gasp, sob and guffaw at their epic grotesqueness. Critics have described her work as a “journey in uchronia,” or a hypothetical alternate history. When asked by Sarah Kent of The Arts Desk if she was “confronting American history in order that the process of forgiveness can begin?” Walker responded: “It seems to go that way except that I have a trickster view. I get things out in the air and then embellish them. I think of myself as an unreliable narrator, a mistake machine.”

Although Walker has become a darling of the art world (the original “The Emancipation Approximation” recently sold for $125,000), not everyone is convinced that the artist has noble intentions. Detractors, led by the renowned African-American artists Betye Saar and Howardena Pindell, have accused her of catering her imagery to white audiences, that she is perpetuating stereotypes rather than dismantling them. When I bring this up to DiTillio, she nods, saying that Emancipating the Past is one of the JSMA’s most challenging exhibits.

“I’ve definitely had that kind of soul searching; when I think about my own reaction to her work and to the stereotypes that she’s presenting, it’s not like looking at her work makes me believe those stereotypes … It makes me think about the way those are kind of naturalized in our culture,” she says. “The idea that she’s making these images for a white audience to entertain us is really problematic. It doesn’t give the viewer enough credit to think critically about the images she’s showing you. It makes it sound like we’re just looking at Walker’s art like we watch TV. It’s not what her art allows you to do. You have to think about it.”

Learning from Lasting Legacies

The JSMA staff has reached out to local organizations, like the NAACP and the UO Black Student Union, to help disseminate the Kara Walker exhibit throughout the community.

“The U.S. is still dealing with race,” says Eric Richardson, the president of the Eugene-Springfield chapter of the NAACP. “White audiences are part of the story and solution. It’s not like black audiences should only be painting for and speaking to black people. There’s a lot of different issues that can be brought up around her work.”

Richardson was immediately enthusiastic about getting involved, seeing it as an opportunity to have an open dialogue about the racism that persists today. “There’s a great legacy here,” he says. “A lot of people may not know it, but [Eugene] has a strong history of an African-American presence.”

He has invited the JSMA staff to present a three-minute preview video of the exhibit at the annual community MLK March hosted by the local NAACP Jan. 20. Giancarlo Esposito, who has starred in Spike Lee’s School Daze and Do the Right Thing, and most recently as drug kingpin Gus Fring in Breaking Bad, will be the event’s keynote speaker.

“I might get backlash from this,” Richardson says, explaining that the NAACP is traditionally a conservative organization with a strong association with the church. But, he notes, “I understand the resistance to dealing with these tough issues. There is avoidance in the African-American community. It’s very difficult and it’s work,” but “sweeping it under the rug is not the healthy way to go.”

Many claim that with a black president, we live in a “post-racial” society. Part of the reason people may want to believe this is because the racism of today is different than that of the past. “It’s very subtle. It’s both individual and it’s institutional,” Richardson says. He points to the recent death of the trailblazing author Amiri Baraka as an example — no local newspapers recognized the loss.

“If you’re a local black here, it’s been very difficult to rise up and succeed on a lot of levels,” he says, adding that the problem lies with discrimination in the local school systems and police department. “Tension that whites feel with other races still exists.”

LCC instructor, Gang Prevention Task Force co-chair and EW columnist Mark Harris agrees. In EW’s recent “I Dream of Eugene” cover story (Dec. 26), Harris called for a “Lane County Truth and Reconciliation Commission, like the one that happened in South Africa, to reveal and come clean about the history, recent and present policies and realities around race and other intersectional forms of patterned discrimination.”

One of the histories Harris would like to see Lane County come clean about is its history with the Ku Klux Klan. At one point, “the Klan was organized out of the university,” says Harris, who has spent years researching Oregon’s racial history with his partner Cheri Turpin. And although many claim that the Klan died out here in the 1920s, he has found historical documentation saying otherwise. “We notice Klan activity well into the 1970s.”

Then there’s the sundown laws. “The sundown laws in Eugene specifically don’t mention race, they mention vagrancy,” Harris says, meaning that if you didn’t own property in Eugene, which blacks were banned from doing, it was illegal for you to stay within city limits after dark. “It was illegal for blacks to live within the city limits until 1965.”

Much of Harris and Turpin’s local research, which they plan to publish in an upcoming book, overlaps with the statewide research of Walidah Imarisha, an author, poet and professor in Portland State University’s Black Studies department. To spur on productive conversations about race in the community, the JSMA invited Imarisha to join the Walker exhibit’s progam; she will be giving her talk “Why Aren’t There More Black People in Oregon? A Hidden History” Sunday, Feb. 23, at the Eugene Public Library. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, African-Americans and people of “two or more races” made up about 5.5 percent of Oregon’s population as of 2012.

“I’ve done this program across the state. Overwhelmingly, I always get a full house. The reason there is such a large turnout is because people want to have these conversations. People look around and see the landscape around them and want to know why,” Imarisha tells EW. “The response has been overwhelmingly positive.” Imarisha discusses Oregon history that rarely comes up in public classrooms, like that Oregon was the first state in the union with a constitution that prohibited slavery, but banned freed blacks from living in Oregon.

Imarisha says that her audiences are “incredibly surprised to learn about the racial exclusionary clause,” which remained in the constitution until 1926, and that the 15th Amendment, allowing black people to vote, was not ratified by the Oregon government until 1973 — over 100 years after it was passed by the federal government. African-Americans were essentially Oregon’s first “illegal aliens.” Another piece that is shocking for people, she adds, is the size of the presence of the Klan, which at its state peak reached 200,000 members. “We also had a Klan governor — Walter Pierce,” she says.

“This is Oregon history. It does affect every person’s life in Oregon,” she says. “This is a history we are all responsible for. There are people of color everywhere. There are people of color in almost every town and every county. These folks are carrying with them this living legacy on their bodies everyday. We all carry this same burden.”

In wrapping up my conversation with Schnitzer, he points out that Walker “has the guts to reach inside her heart and pull out her history.” He notes that, being Jewish, he can relate to this experience when going to Holocaust museums. “These themes are difficult to deal with. They hurt,” he says.

“We’re a pretty waspish, white Caucasian state. Why is [the exhibit] important to the UO, to Oregon?” Schnitzer ponders. “Every university has that obligation, not a choice, an obligation to be a center of analysis, discourse, reflection. Young people come that are blocks of clay. We are constant works of art, each of us … The subjects of bigotry, tolerance and injustice are critical issues that must be taught.” He adds, “We can never let up our vigil about the sanctity of life and the morality of mutual respect and tolerance.”

Emancipating the Past: Kara Walker’s Tales of Slavery and Power runs Jan. 24 through April 6. For more information about exhibit programming, visit jsma.uoregon.edu/KaraWalker. For more information about the 2014 Annual Community MLK March, visit naacplanecounty.org.

|

| ‘The Emancipation Approximation’ |

|

| ‘African/American’ |

|

| ‘Testimony’ |

|

| ‘Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching’ |